| Clin Mol Hepatol > Volume 19(4); 2013 > Article |

Sclerosing hemangioma of the liver is an unusual tumor type. Because of its rarity and atypical radiologic findings, sclerosing hemangiomas can be difficult to distinguish from other lesions such as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, metastasis, and organized abscesses. In this issue, we present a case consisting of both hepatic sclerosing hemangioma and cavernous hemangioma in a 63-year-old woman and discuss the histopathologic findings.

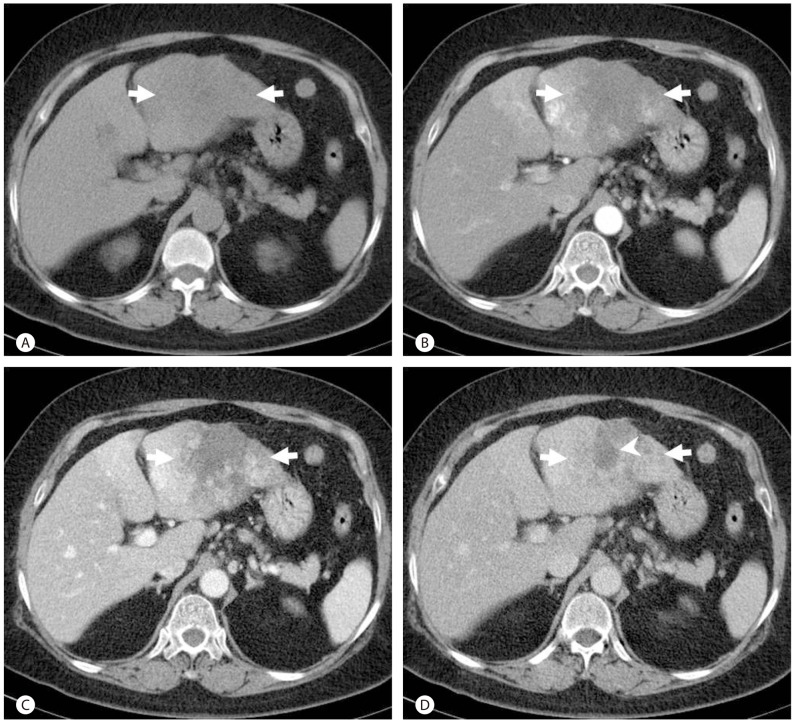

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for evaluation of a hepatic mass. The patient had visited a private clinic because of abdominal pain and a hepatic mass that was suspected to be a hepatocellular carcinoma. She had a history of multiple stable liver masses suspected to be hemangiomas diagnosed over twenty years prior to her visit. The patient had been on an oral contraceptive briefly for treatment of endometrial hyperplasia in her mid-forties. Physical examination was unremarkable. The serum level for aspartate aminotransferase was 49 IU/L (normal range, 12-33 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase was 56 IU/L (normal range, 5-35 IU/L), and gamma glutamyl transferase was 151 IU/L (normal range, 8-48 IU/L), while all other liver function tests were within normal limits. Serum tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein and PIVKA-II were within normal limits. Serologic tests for hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus were negative. Complete blood count revealed anemia; however, leukocytosis and eosinophilia were not noted. Dynamic contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 9.0├Ś7.1 cm sized irregular shaped mass in the left lateral section of the liver. The mass showed heterogeneous low attenuation on unenhanced CT, and there was no evidence of internal calcification or fat (Fig. 1A). After administration of intravenous contrast media, multifocal patchy irregular enhancement in the peripheral area was seen during the arterial phase (Fig. 1B). During portal venous and delayed phases, patchy progressive centripetal enhancement was noted (Fig. 1C, D). Multifocal low attenuated areas seen on unenhanced CT were consistently noted as low attenuations on dynamic images. A fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan showed multiple areas of increased FDG uptake in the peripheral area of the mass in the left lobe of the liver. A separate 3.0├Ś2.1 cm sized mass in the left lateral section of the liver was observed adjacent to the main mass, which displayed centripetal progressive enhancement with bright vascular enhancement consistent with cavernous hemangioma. The patient underwent a left lateral segmentectomy. Fifty months after surgery, the patient's course remained uneventful.

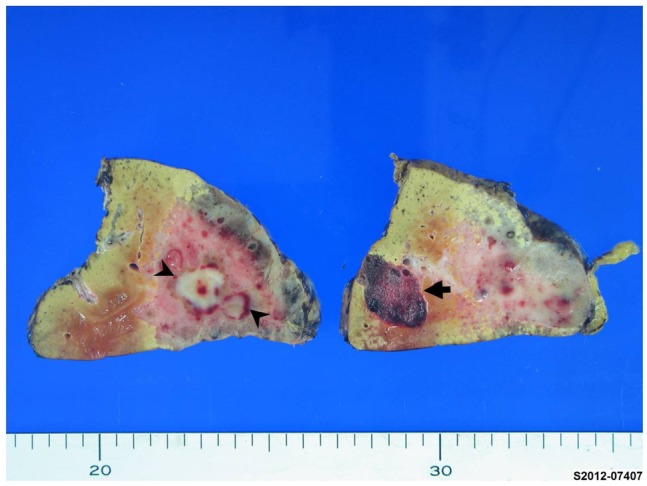

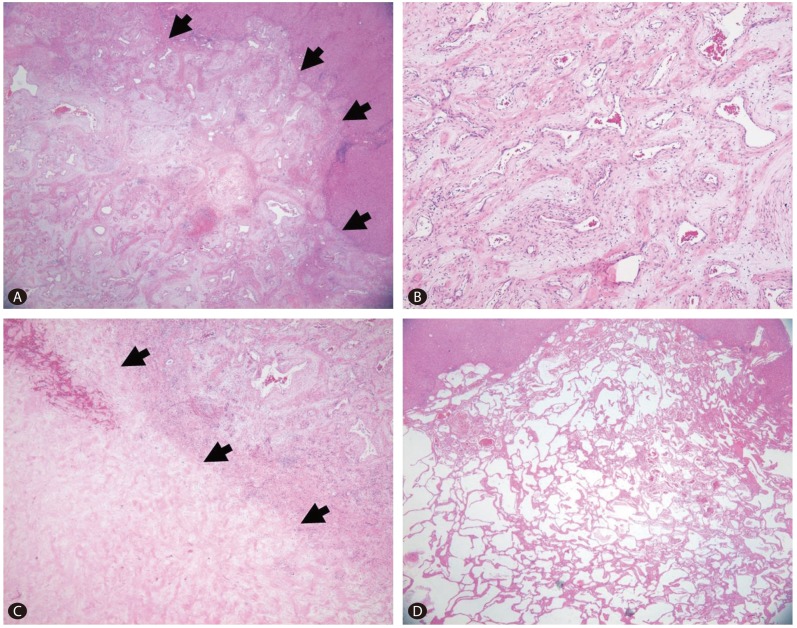

On the cut section, two masses were identified from the surrounding liver. The first one was a 9.1├Ś5.3 cm, pinkish-gray, solid, ill-demarcated mass with multiple hemorrhagic foci with a 1.8├Ś1.3 cm sized grayish white distinguishable area in the center of mass that was also more firm. The second mass was 2.6├Ś1.6 cm in size and well-demarcated with a dark red, sponge-like mass composed of blood-filled cavities (Fig. 2). Microscopically, the larger mass exhibited proliferation of variable sized vessels with thickened myxoid walls and flattened endothelial lining without cytologic atypia or mitotic activity (Fig. 3A, B). There was a central acellular sclerotic zone that was composed of dense sclerotic hyalinized collagenous tissue with scattered tiny vascular channels with collapsed lumen. This area corresponded to a low-attenuated area in the central portion of the mass on dynamic CT. On the basis of these pathological findings, the mass was diagnosed as a sclerosing hemangioma with a central hyalinized portion (Fig. 3C). The smaller mass was consistent with a cavernous hemangioma, with multiple vascular spaces of various sizes lined by a single layer of flattened cells (Fig. 3D).

Hepatic sclerosing hemangiomas and sclerosed hemangiomas are rare conditions that were first reported by Shepherd and Lee in 1983.1 A subsequent report of two more solitary "necrotic nodules" of the liver identified a vascular component, suggesting a probable pathogenesis of sclerosis of a preexisting hemangioma.2 In 2002, Makhlouf and Ishak compared the distinct clinical and histopathological findings between sclerosing and sclerosed hemangioma of the liver,3 suggesting possible involvement of mast cells in angiogenesis, the regression process, and development of fibrosis. In addition, they demonstrated that sclerosing hemangiomas exhibit immunoreactivity for collagen IV, laminin, factor VIII-R antigen, CD34 and CD31, as well as increased immunoreactivity for smooth muscle actin more frequently compared with sclerosed hemangiomas.

Clinical data of sclerosing hemangiomas are limited because of the small number of reported cases. However, according to the cases reported to date, sclerosing hemangiomas are mainly present in individuals who are sixty to seventy years old and, unlike typical hemangiomas, are predominantly observed in males (67% of 24 cases). Almost 40% of all sclerosing hemangioma patients are symptomatic, with the major symptoms consisting of abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, indigestion, and abdominal distention. The majority of sclerosing hemangiomas are solitary, although multiple lesions are occasionally observed, as was the case in the present study. In addition, in cases of multiple sclerosing hemangiomas, the tumor size is larger than that of single sclerosed hemangiomas.3-8

There have been only a few studies to report radiological findings of sclerosing hemangiomas. Yamashita et al8 reported that sclerosing hemangiomas exhibit only marginal enhancement on CT hepatic arteriography, whereas the majority of the tumor presents as a perfusion defect. In addition, Lee et al9 reported that sclerosing hemangiomas exhibit mild to moderate hyperintensity on T2 weighted MR images, hypointensity on T1 weighted images, patchy enhancement during the arterial phase, and gradual progressive enhancement during the portal and delayed phases except in the central area. The most recent study on sclerosing hemangiomas reported centripetal patchy enhancement with a partial central unenhanced area on CT and MRI, with iso- to hypo-metabolism on FDG-PET scans.5 Pathologically, these atypical radiological features are due to prominent sclerosis and marked narrowing of the vascular spaces. According to the above imaging findings, differentiation of sclerosing hemangioma from hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, metastasis, or organized abscesses constitutes a diagnostic challenge that may require pathological confirmation in some cases.

According to a microscopic definition, a 'sclerosing hemangioma' is a neoplasm composed of blood-filled, dilated, and thin-walled vessels of variable size lined by a single layer of flat endothelial cells without cytologic atypia or mitotic activity.8 The vascular spaces are frequently collapsed, some of which can have an arterial wall. Sclerosis of the stroma may occur at varying degrees to mask the appearance of the hemangioma, and can vary from scanty (fibrillar or hyaline) to abundant (hyaline or sclerotic), with most of the lesions having a sclerotic center with patent vessels at the periphery.8 However, these vessels can be alternates that in some cases disperse within the sclerotic mass. In addition, some vascular channels are surrounded by a loose myxoid matrix and a concentric cuff of stellate cells. Recent hemorrhages and hemosiderin deposits are found in the majority of sclerosing hemangiomas and are often associated with dystrophic and psammomatous calcification or infarction.3 The basement membrane of a sclerosing hemangioma can be detected by type IV collagen and laminin immunostaining, which form rings around the vascular components. The vascular nature of such hemangiomas is exemplified by strong positive staining for endothelial cell markers, factor VIII-related antigen, CD34, and CD31. The densely sclerotic areas are focally and faintly positive for these vascular markers.3,8 On the other hand, sclerosed hemangiomas are characterized by extensive fibrosis with subsequent hyalinization and marked narrowing or obliteration of the vascular spaces.10 Compared with sclerosing hemangiomas, the entire lesion is diffusely sclerotic and appears as a firm, gray-white nodule in sclerosed hemangiomas.3

The pathogenesis of sclerosing hemangiomas remains unknown and has no definite familial or genetic factor of inheritance, although several theories have been proposed. The first theory is that a minor hemorrhage and thrombosis within a hemangioma may instigate fibrotic progression to a sclerosing hemangioma.4 An additional theory proposed by Makhlouf et al3 suggests that mast cells play a pivotal role in the development of a sclerosing hemangioma. In support of this possibility, they reported that the number of mast cells correlates significantly with vascular proliferation and is inversely related to the degree of fibrosis. According to previous reports, sclerosing hemangiomas arise in cavernous hemangiomas with thin-walled cavernous vascular spaces of variable size that lack an elastic tissue.3 The terms cavernous hemangioma, sclerosing hemangioma, and solitary fibrous nodule have been used to describe different stages in the development and involution of the same lesions.11 The sclerotic area in a sclerosing cavernous hemangioma is best explained by localized regressive changes secondary to thrombosis, infarction, or hemorrhage. On the other hand, the description of sclerosed hemangiomas suggests a possible origin from infantile hemangioendotheliomas. They are not considered to have evolved from cavernous hemangiomas on the basis of their morphology consisting of a scattered array of uniform, small sclerotic vessels compatible with capillary type channels rather than cavernous type channels.3 Moreover, total hyalinization that resembles a solitary necrotic nodule is common in sclerosed hemangiomas, but not in sclerosing hemangiomas.

In the patient described in this study, two masses were detected on CT twenty years prior to her diagnosis. From the time of the first occurrence, the mass that was diagnosed as a sclerosing hemangioma demonstrated atypical radiologic features, and thus needed to be differentiated from hepatocellular carcinoma and other atypical tumors. Sclerosing hemangiomas are benign tumors that remain stable for long periods of time and can be followed without treatment. However, as was the case with our patient, when the size of the tumor is sufficiently large to cause symptoms, appropriate treatment is necessary.

REFERENCES

1. Shepherd NA, Lee G. Solitary necrotic nodules of the liver simulating hepatic metastases. J Clin Pathol 1983;36:1181-1183. 6619314.

2. Berry CL. Solitary "necrotic nodule" of the liver: a probable pathogenesis. J Clin Pathol 1985;38:1278-1280. 4066988.

3. Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG. Sclerosed hemangioma and sclerosing cavernous hemangioma of the liver: a comparative clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with emphasis on the role of mast cells in their histogenesis. Liver 2002;22:70-78. 11906621.

4. Papafragkakis H, Moehlen M, Garcia-Buitrago MT, Madrazo B, Island E, Martin P. A case of a ruptured sclerosing liver hemangioma. Int J Hepatol 2011;2011:942360. 21994877.

6. Lauder C, Garcea G, Kanhere H, Maddern GJ. Sclerosing haemangiomas of the liver: Two cases of mistaken identity. HPB Surg 2009;2009:473591. 20066166.

7. Choi YJ, Kim KW, Cha EY, Song JS, Yu E, Lee MG. Case report. Sclerosing liver haemangioma with pericapillary smooth muscle proliferation: atypical CT and MR findings with pathological correlation. Br J Radiol 2008;81:e162-e165. 18487382.

8. Yamashita Y, Shimada M, Taguchi K, Gion T, Hasegawa H, Utsunomiya T, et al. Hepatic sclerosing hemangioma mimicking a metastatic liver tumor: report of a case. Surg Today 2000;30:849-852. 11039718.

9. Lee VT, Magnaye M, Tan HW, Thng CH, Ooi LL. Sclerosing haemangioma mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Singapore Med J 2005;46:140-143. 15735880.

10. Mathieu D, Rahmouni A, Vasile N, Jazaerli N, Duvoux C, Tran VJ, et al. Sclerosed liver hemangioma mimicking malignant tumor at MR imaging: pathologic correlation. J Magn Reson Imaging 1994;4:506-508. 8061455.

11. Miettinen , Fletcher CDM, Kindblom LG, Zimmermann A, Tsui WMS. Mesenchymal tumours of the liver. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro Fatima, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010. p. 241-250.

Figure┬Ā1

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT images of a 64-year-old woman with a sclerosing hemangioma of the liver. A precontrast CT scan revealed a large irregular shaped mass with heterogeneous low attenuation in the left lobe of the liver (arrows) (A). Arterial (B), portal (C) and delayed (D) phases of CT scans revealed heterogeneous enhancement in the peripheral area of the mass (arrows) with a gradual centripetal enhancement pattern except for a central area of persistent low attenuation corresponding to sclerosis by histopathology (arrow head).

Figure┬Ā2

Macroscopic findings of a sclerosing hemangioma and cavernous hemangioma. A sclerosing hemangioma was observed as a 9.1├Ś5.3 cm sized, ill-demarcated, pinkish-gray subcapsular mass with multiple hemorrhagic foci. A 1.8├Ś1.3 cm sized grayish white area (arrow heads) was centrally located within the tumor. A cavernous hemangioma appearing as a discrete, dark red, sponge-like subcapsular mass was observed adjacent to the sclerosing hemangioma (arrow).

Figure┬Ā3

Sclerosing hemangioma (arrows) consisting of variable-sized vessels with thickened myxoid walls (A). Small irregular vessels lined by a flattened endothelium and erythrocytes in the lumen (B). Inflammatory infiltrates, including lymphocytes and plasma cells, were noted in the stroma. A central portion of the sparsely cellular hyalinized area (arrows) was seen abutting the area of small vascular channels (C). The cavernous hemangioma consisted of multiple thin-walled vascular spaces of various sizes and lined by a single layer of flattened endothelial cells that was filled with fresh erythrocytes in some areas (D).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print