INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous liver biopsy was first introduced in 1883 [

1]. Since then, it has been the gold standard for the evaluation of liver disease. According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease guidelines, liver biopsy is an essential diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of parenchymal liver disease, and the evaluation of inflammation and fevers of unknown origin [

2]. However, liver biopsy is an invasive procedure associated with several complications. The most common complications were abdominal pain, which was reported in almost 30% of the patients, followed by bleeding (0.3%) and death (0.03%), respectively [

3]. However, these complication rates have been reported mainly in blind liver biopsies, and the complication rate is expected to decrease significantly under ultrasonography-guided liver biopsies [

4]. Currently, image-guided liver biopsies have replaced traditional blind liver biopsies. It is widely used to maximize the effectiveness of the procedure and minimize the complication rate [

5].

Recently, many noninvasive methods have been developed to replace liver biopsies [

6]. The most widely used noninvasive test is transient elastography. It has been used since 2005 to stage liver fibrosis and steatosis [

7]. Two-dimensional shear wave elastography can be used to determine the fibrosis stage of the liver based on the concurrent real-time grayscale [

8]. Moreover, magnetic resonance electrography can also be used to evaluate the entire liver fibrosis stage and is widely used to replace liver biopsies in clinical trials, especially phase II trials [

9,

10]. Therefore, the role of a traditional liver biopsy is expected to change significantly in the immediate future.

In this study, we evaluated the changes in liver biopsy indications over the past 18 years and the safety of ultrasonography-guided liver biopsies in the era of noninvasive assessments of liver fibrosis.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population according to the year of the liver biopsy. A total of 1,944 patients underwent liver biopsies over the last 18 years. The median age of the study population was 48 years and 58% was male. The median age of the study population and the proportion of females tended to increase significantly over time. Despite advising patients to abstain from antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants, nine patients (1.97%) continued taking antiplatelet agents, and one patient was undergoing warfarin treatment. These patients underwent biopsies after discontinuing the drug for 3 days after hospitalization.

Changes in liver biopsy indications over time

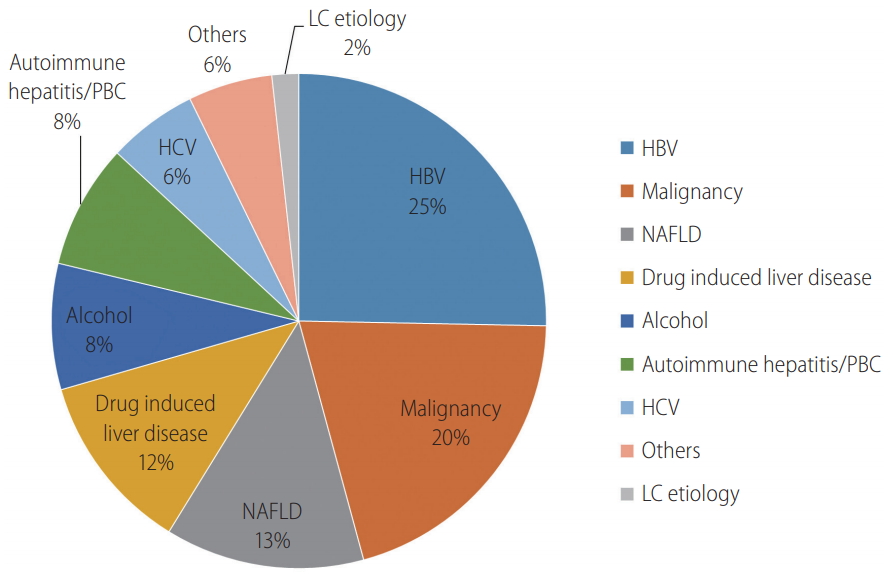

In all 1994 patients, hepatitis B virus (HBV) was the most common indication for a liver biopsy (25.3%), followed by suspected malignancy (20.5%), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (13.0%), drug-induced liver disease (DILI) (11.7%), and alcohol-related liver disease (8.2%) during the overall study period (

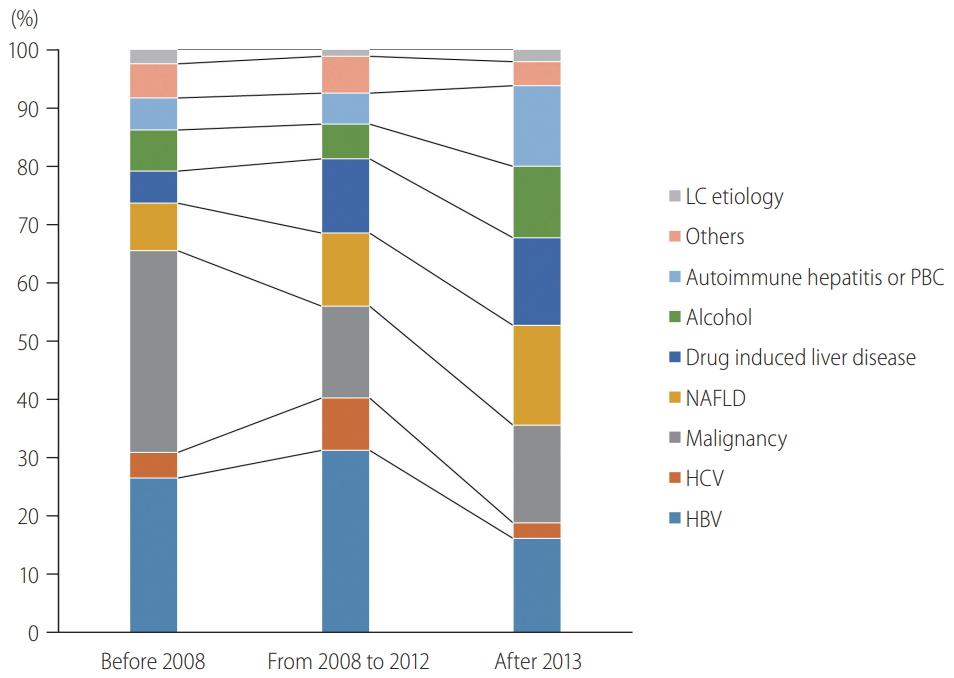

Fig. 1). The top three major indications for a liver biopsy were consistently chronic hepatitis B, malignancy, and NAFLD, but the priority of the indications changed over time (

Table 2). Before 2008, malignancy (34.6%) and chronic HBV (26.5%) accounted for more than 50% of the liver biopsy indications. From 2008 to 2012, the most common indication was chronic HBV (31.3%), followed by malignancy (15.7%) and NAFLD (12.6%). In the 5 years since 2013, the proportion of each of the three main indications was similar, with NAFLD accounting for the highest proportion, at 17.2%.

Figure 2 shows that liver biopsies for chronic hepatitis B and C increased by 2012, accounting for 40.3% of the total. In the last 5 years since 2013, the proportion of viral hepatitis decreased substantially to 18.9%. Liver biopsies to distinguish malignancies also declined since 2008, from 34.6% to 16.7%. In contrast, liver biopsies for NAFLD and DILI increased gradually from 8.1% to 17.2% and 5.5% to 14.9%, respectively, since 2008. The proportion of biopsies for alcohol-related liver disease and autoimmune hepatitis/primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) did not change until 2012. However, since 2013, they have increased sharply from 5.9% to 12.2% and 5.4% to 13.8%, respectively.

Discordances in diagnoses before and after liver biopsies

Table 3 shows the diagnostic agreement before and after biopsy. There were 51 cases (2.6%) of discordance between the suspected diagnosis and the final diagnosis. The 51 discordant cases included 19 cases of suspected malignancies and 17 cases of suspected DILI. Of the 19 patients with suspected malignancies, 10 were finally diagnosed as benign masses, such as hemangioma (52.6%), and the remaining nine were diagnosed with other diseases. Of the 17 patients suspected with DILI, 11 (64.7%) were finally diagnosed as autoimmune hepatitis, PBC or overlap syndrome, and five (29.4%) as NAFLD. However, eight patients suspected of autoimmune hepatitis or PBC proved to be NAFLD or DILI after the liver biopsies.

In addition, there were two noticeable discordant cases. A 58-year-old male was suspected to have liver cirrhosis but it was difficult to identify whether the cause of the cirrhosis was HBV or alcohol by serological and radiological testing. However, after the liver biopsy, the pathologic analysis indicated that the main cause of the chronic liver injury was alcohol rather than HBV. Valuable information was obtained from the liver biopsy, and without the liver biopsy, it would not have been possible to accurately diagnose the patient using only his history or laboratory results. The second noticeable discordant case was a 48-year-old female diagnosed with a benign mass, although the suspected diagnosis was focal fat-sparing before the liver biopsy. She had a hypoechoic lesion in the background of fatty liver by ultrasonography and was suspected to have a fatty liver with a focal fat-sparing zone. Additional CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tests could not differentiate between the focal fat-sparing zone vs. the benign mass in aspects such as focal nodular hyperplasia. A targeted liver biopsy was performed for the differential diagnosis of the focal lesion and it was finally confirmed as a hemangioma.

Liver biopsy in cirrhosis

Among the 1,944 patients included in the study population, 563 (30.0%) had liver cirrhosis at the time of their liver biopsy. In these patients, a liver biopsy was conducted to determine the etiology of the liver cirrhosis and accurately determine the degree of liver fibrosis. Most of the pre-biopsy diagnoses were consistent with the final diagnoses, including cryptogenic liver cirrhosis. However, in contrast, the histological results of these patients revealed that 16% (90 of 563) had no liver cirrhosis. The histological results of the patients diagnosed with cirrhosis by ultrasound were: F1 (nine patients, 1.60%), F2 (six patients, 1.07%), F3 (75 patients, 13.32%), and F4 (473 patients, 84.01%). As shown in

Table 4, the patients with cirrhosis were significantly older than those without cirrhosis (median age of 53 years vs. 45 years) and comprised a higher proportion of males (66.1% vs. 55.2%). Among the cirrhotic patients, 20.2% of the patients showed ascites. Four hundred thirty-nine patients (78.0%) were Child-Pugh class A and 124 (20.7%) were Child-Pugh class B or C. The median model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 8.7. The presence of cirrhosis did not affect the frequency of complications (

P=0.289).

Complications after liver biopsy

Painkillers were prescribed during hospitalization for 116 patients (6.0%) because of pain and there was no record of hypotension or pneumothorax. However, this was a retrospective study and thus, these minor complications may have been underestimated.

The major complication rate was 0.05%. A single major complication associated with a liver biopsy occurred during the study period. The patient was a 61-year-old female who had cryptogenic liver cirrhosis. She had thrombocytopenia (71,000/┬ĄL) and prolonged prothrombin time (15.5 seconds). Her baseline Child-Pugh score was 6, and her MELD score was 13. The liver biopsy was done without immediate complications and the patient was discharged without procedure-related complications by abdominal ultrasonography. However, four days post-liver biopsy, the patient was re-admitted due to abdominal pain and delayed bleeding from the biopsy site was found. The patientŌĆÖs vital signs and laboratory findings, including hemoglobin, were stable and no procedure was required for hemostasis. The patient was discharged successfully after supportive care for 5 days.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed all of the cases of ultrasonography-guided percutaneous liver biopsies for the past 18 years. Currently, percutaneous liver biopsy under ultrasonography guidance has been the most generally used method. Only when there were specific reasons, such as high bleeding tendency or large amounts of perihepatic ascites, were transjugular or CT-guided liver biopsies performed instead of ultrasonography-guided percutaneous liver biopsies. We included only patients who underwent ultrasonography-guided percutaneous liver biopsies to exclude those extreme cases and analyze a homogenous and standardized liver biopsy study population. The number of liver biopsies decreased from 2013 to 2018 and the indications for liver biopsies also changed by the period. The most common indication for liver biopsy during the entire study period was chronic HBV, followed by malignancy, and NAFLD. However, since 2013, the rate of NAFLD has increased rapidly, making it the most common indication. The rate of liver biopsies for chronic HBV and malignancy has declined, whereas the incidence of DILI, alcohol-related liver disease, and autoimmune hepatitis/PBC has increased sharply in the recent 5 years. Overall, a major adverse event of delayed bleeding at the biopsy site was identified, which was resolved by conservative management.

The decrease in liver biopsies for viral hepatitis was mainly attributed to the development of noninvasive methods for the assessment of liver fibrosis; the introduction of potent antiviral agents, such as entecavir, tenofovir, and direct-acting agents for hepatitis C; and the expansion of indications for antiviral treatment. In addition, advances in radiologic imaging techniques have reduced the number of liver biopsies for malignancies. Fatty liver has recently emerged as a major etiological factor underlying liver disease, which has rapidly increased the number of liver biopsies for NAFLD. These dynamic changes in indications for liver biopsy showed epidemiological changes over time in the study population.

Liver biopsy has been considered the most specific test to assess liver disease [

1]. However, the clinical usefulness and impact of liver biopsies have been underestimated in the recent two decades due to the development of alternative noninvasive tests and new insight into the limitations of liver biopsies [

13]. Various types of liver elastography have been developed, with relatively accurate assessments of advanced liver fibrosis. The combination of medical history, serologic and radiologic evaluation, and liver elastography is adequate for the diagnosis of liver disease in most instances [

14]. In terms of solid liver lesions, multiphasic contrastenhanced CT or MRI can discern focal liver lesions in most cases. With the development of imaging techniques, a liver biopsy is rarely needed to distinguish focal liver lesions.

Liver biopsies, however, have their own unique role in the differential diagnosis and management of various liver diseases. A liver biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis, PBCŌĆöespecially anti-mitochondrial antibody-negativeŌĆöand several rare infiltrative diseases, such as amyloidosis and the hepatic involvement of lymphoma [

13]. In addition, only liver biopsy can differentiate simple steatosis from steatohepatitis in current clinical practice, which is important in treatment decisions in specific cases of chronic HBV infections [

15,

16]. For the diagnosis of malignant tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), histological confirmation is the most specific and useful method, especially when imaging findings are ambiguous. In fact, a retrospective analysis of the UNOS/OPTN database reported that 20.9% of the 789 patients who underwent liver transplantation for HCC were finally diagnosed with benign nodules [

17]. In our study as well, a considerable discrepancy (2.6%) existed between the suspected diagnosis before liver biopsy and the final diagnosis. These results suggest the clinical importance of liver biopsies despite the development of noninvasive tests. In addition, among 563 patients who had ultrasonographic liver cirrhosis in this study, 16% were revealed not to have histologic liver cirrhosis. The ability to differentially diagnose the presence of liver cirrhosis and assess the exact fibrosis stage, as well as determine the etiology of chronic liver disease, is critical in several situations, especially to establish disease-specific treatments, such as antiviral therapy in viral hepatitis and steroid therapy in alcohol-related liver disease. Liver biopsies complement noninvasive methods, playing a critical role in the evaluation and management of liver fibrosis [

10,

18].

In terms of safety, our study reported a substantially lower rate of major complications (0.05%) than previous reports. In addition, we found that liver biopsies were safe in patients with cirrhosis and/or ascites, contrary to the concerns of clinicians. Some studies have reported that perihepatic ascites did not significantly affect the major and minor complication rates of image-guided percutaneous liver biopsies [

19,

20]. In this sense, most guidelines recommend total paracentesis before the biopsy, rather than prohibiting percutaneous liver biopsies in patients with tense ascites [

21]. We think that the reason for the low complication rate was mainly due to the use of ultrasonography.

There were several limitations associated with this study mainly due to its retrospective format. Minor complications, such as pain, could not be fully investigated because of the retrospective design. Therefore, the incidence of complications may be underestimated. Second, since this study was conducted in a single institution, it may not represent all patient types. However, some generalizations are possible because several doctors had performed liver biopsies independently even in a single institution and we examined all patients who underwent liver biopsies in the institution over 18 years, achieving a large study population. To represent the dynamic changes in liver biopsy indications in South Korea, further multicenter studies to validate our results are necessary.

In conclusion, a liver biopsy is an irreplaceable diagnostic method, even in this era of noninvasive techniques. Also, we found that ultrasonography-guided liver biopsy was safe for patients with liver cirrhosis.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print