| Clin Mol Hepatol > Volume 20(2); 2014 > Article |

ABSTRACT

Pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) have rarely been reported as an extrahepatic manifestation of acute hepatitis A (AHA). We report herein a case of AHA complicated by both PRCA and AIHA. A 49-year-old female with a diagnosis of AHA presented with severe anemia (hemoglobin level, 6.9 g/dL) during her clinical course. A diagnostic workup revealed AIHA and PRCA as the cause of the anemia. The patient was treated with an initial transfusion and corticosteroid therapy. Her anemia and liver function test were completely recovered by 9 months after the initial presentation. We review the clinical features and therapeutic strategies for this rare case of extrahepatic manifestation of AHA.

Acute hepatitis A (AHA) is usually a mild and self-limited infection, especially when infected in early childhood.1 However, rarely, AHA can be complicated by extrahepatic manifestations, such as rash, arthralgia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, arthritis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, myocarditis, renal failure, optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, or polyneuritis etc.2,3,4,5,6,7,8

Pure red cell anemia (PRCA) and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) are another rare extrahepatic manifestation of AHA. When complicated with PRCA and AIHA, it may contribute to significantly greater morbidity and mortality in AHA.9 We experienced a case of AHA complicated by both PRCA and AIHA, and we herein report this rare extrahepatic manifestation of AHA with a review of the treatment strategies.

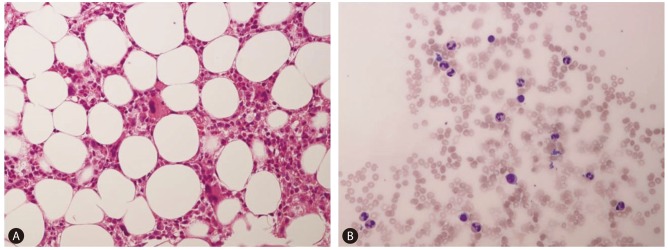

A 49-year old previously healthy woman admitted our hospital with a febrile sense, myalgia and nausea for 5 days. Initial laboratory findings showed marked elevation of serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 6,122 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 7,451 IU/L, total bilirubin (TB) 5.1 mg/dL, and prolonged prothrombin time (PT-INR) 1.76. Complete blood count was within normal limit except for thrombocytopenia (hemoglobin (Hb) 14.8 g/dL, white blood cell (WBC) 6,790/┬ĄL, platelet 118 ├Ś 103/┬ĄL). Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular Hb (MCH) were 82.4 fL and 28.3 pg, respectively. Serologic tests revealed negative results for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibody, and positive result for anti-hepatitis C virus IgM. Based on clinical and laboratory findings, she was diagnosed with AHA. Her symptoms and laboratory results were gradually improved during hospitalization as AST 916 IU/L, ALT 1925 IU/L, TB 9.2 mg/dL, PT-INR 1.37, and discharged after 5 days of admission. Her serum Hb level at discharge was 14.3 g/dL. Three weeks later, she re-admitted to hospital because of jaundice and a poor general condition. Laboratory examination illustrated marked elevation of TB, 32.3 mg/dL with severe anemia (Hb, 6.9 g/dL, MCV 77.4 fL, MCH 26.4 pg). At this time, there was improvement in serum AST and ALT and PT-INR levels compared to those at the time of discharge from hospital (AST 147 IU/L/L, ALT 114 IU/L, PT-INR 1.15). She had no symptoms or signs suggesting gastrointestinal bleeding (Levin tube irrigation: no signs of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, digital rectal examination: no signs of gastrointestinal bleeding). Laboratory examination revealed elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level (1,600 IU/L), positive direct Coombs test, decreased haptoglobin level (<20 mg/dL) and positive hemoglobinuria, which confirmed the presence of AIHA. However, reticulocyte count (reticulocyte 0.08%, corrected reticulocyte count 0.04%, reticulocyte production index 0.02%) was decreased, suggesting that additional causes of anemia other than AIHA may be present. Hence, bone marrow examination was conducted, which revealed normocellular marrow (cellularity 35%) and active granulopoiesis with markedly decreased erythroid cells (myeloid: erythroid=24.9:1). Hemophagocytosis and any other necrosis were not observed (Fig. 1). Based on the results of bone marrow examination, PRCA was diagnosed for the patient. Parvovirus B19 IgM and Epstein-Barr virus VCA IgM were tested to see whether these two virus co-existed, and showed negative test results.

She was treated with prednisolone (1 mg/kg), but her Hb level continued to drop, and was 4.7 g/dL on 3rd day of predinisolone treatment. She received two pints of packed red blood cells (RBC), and continued corticosteroid therapy. After transfusion, her Hb level was 7.7 g/dL, and was gradually increased, reaching 10.4 g/dL two weeks later. Reticulocyte count was increased to 15.9%, and serum TB and LDH level were decreased to 19.4 mg/dL and 927 IU/L, respectively, at that time. Prednisolone was administered at dose of 1 mg/kg for 1 month, and then the dose was tapered over two months periods. Hb level was normalized (13.4 g/dL) in two months following steroid therapy. Her liver function was completely recovered with normal Hb level nine months after initial presentation.

Although rare, AHA is sometimes complicated by hematopoeitc abnormalities, such as AIHA, PRCA, aplastic anemia and hemophagocytic syndrome.3,4,5,9,10 However, AHA complicated by both AIHA and PRCA is extremely rare and only a few cases have been reported worldwide (Table 1).4,11,12 To our knowledge, this is the fourth case that has been reported in the literatures.4,11,12 PRCA is a syndrome characterized by a severe normocytic anemia, reticulocytopenia, and absence of erythroblasts from an otherwise normal bone marrow. It may be present as a primary hematologic disorder or secondary to various diseases like infection including parvovirus and hepatitis virus, collagen vascular disease, leukemia, lymphoma, thymoma and solid tumors.13 A bone marrow aspirate is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis, but a biopsy may be necessary if the bone marrow smear is not optimal. The typical bone marrow examination shows almost complete absence of erythroid precursors, but normal platelet and white cell precursors.14 To achieve remission, treatment with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine A, antithymocyte globulin, splenectomy, and plasmapheresis can be considered. Cortisosteroids are the first choice and prednisone is given orally at a dose of 1 mg/kg/d usually given until remission is induced and can be tapered. In approximately 40% of patients, remission usually occurs within 4 weeks.4,13

AIHA is a rare autoimmune condition in which autoantibodies directed toward RBC antigens lead to their accelerated destruction. The diagnosis of AIHA is usually based on the identification of anti-RBC autoantibodies by means of the direct antiglobulin test, and in most cases, reticulocytosis is accompanied.15 Corticosteroids are the cornerstone of treatment and splenectomy and rituximab are both good alternatives. In cases of severe anemia, rapid transfusion can be expected to produce beneficial results, despite potential risk of alloimmunization.15

In our case, patient displayed both AIHA and PRCA features simultaneously. Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level (1,600 IU/L), positive direct Coombs test, decreased haptoglobin level (<20 mg/dL) and positive hemoglobinuria confirmed the presence of AIHA, and decreased reticulocyte and marked erythroid hypoplasia in bone marrow examination confirmed the presence of PRCA. Patient was previously healthy and had no drug history, negative serology for HBV, HCV, HIV, parvovirus and Epstein-Barr virus and had no evidence of myelodysplastic syndromes, lymphoma and leukemia in bone marrow examination. We were able to rule out hemophagocytic syndrome because the patient didn't have fever, splenomegaly and bicytopenia, and there was no hemophagocytosis in bone marrow.16 Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with PRCA and AIHA, caused by AHA.

Corticosteroid is usually the initial treatment choice in both PRCA and AIHA. Hence steroid therapy can be considered initially under this circumstance. The optimal dose and duration are not known in the setting of PRCA and AIHA in AHA patients due to paucity of relevant data. However, steroid may be tried as in PRCA (at a dose of 1 mg/kg/d usually given until remission is induced and tapered), and this approach seems successful in managing PRCA and AIHA in patients with AHA. Although other measures (plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine A) have been attempted one case (Table 1), while the other cases, including our case, responded well to steroid therapy.

In summary, we experienced an AHA patient complicated by both PRCA and AIHA, who was successfully treated with corticosteroids and initial transfusion.

REFERENCES

1. Jeong SH. Current status and vaccine indication for hepatitis A virus infection in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol 2008;51:331-337. 18604134.

2. Bae YJ, Kim KM, Kim KK, Rho JH, Lee HK, Lee YS, et al. A case of acute hepatitis a complicated by Guillain-Barre syndrome. Korean J Hepatol 2007;13:228-233. 17585196.

3. Jekarl DW, Oh EJ, Park YJ, Han K, Lee SW, Park CW. Acute hemolysis and renal failure caused by hepatitis A infection with underlying glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Korean J Lab Med 2007;27:188-191. 18094574.

4. Lee TH, Oh SJ, Hong S, Lee KB, Park H, Woo HY. Pure red cell aplasia caused by acute hepatitis A. Chonnam Med J 2011;47:51-53. 22111059.

5. Seo JY, Seo DD, Jeon TJ, Oh TH, Shin WC, Choi WC, et al. A case of hemophagocytic syndrome complicated by acute viral hepatitis A infection. Korean J Hepatol 2010;16:79-82. 20375646.

6. Song KS, Kim MJ, Jang CS, Jung HS, Lee HH, Kwon OS, et al. Clinical features of acute viral hepatitis A complicated with acute renal failure. Korean J Hepatol 2007;13:166-173. 17585190.

7. Ko YS, Yoo KD, Hyun YS, Chung HR, Park SY, Kim SM, et al. A case of pleural effusion associated with acute hepatitis A. Korean J Gastroenterol 2010;55:198-202. 20357532.

8. Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ. hepatitis A. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th Edition. PA: Saunders; 2010. Vol 2: p. 1282.

9. Yoon YK, Park DW, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Kim I, Nam MH. Corticosteroid treatment of pure red cell aplasia in a patient with hepatitis A. Acta Haematol 2012;128:60-63. 22627171.

10. Jeong SH, Lee HS. Hepatitis A: clinical manifestations and management. Intervirology 2010;53:15-19. 20068336.

11. Chehal A, Sharara AI, Haidar HA, Haidar J, Bazarbachi A. Acute viral hepatitis A and parvovirus B19 infections complicated by pure red cell aplasia and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J Hepatol 2002;37:163-165. 12076880.

12. Koiso H, Kobayashi S, Ueki K, Hamada T, Tsukamoto N, Karasawa M, et al. Pure red cell aplasia accompanied by autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a patient with type A viral hepatitis. Rinsho Ketsueki 2009;50:424-429. 19483404.

13. Sawada K, Hirokawa M, Fujishima N. Diagnosis and management of acquired pure red cell aplasia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23:249-259. 19327582.

14. Rossert J, Casadevall N, Eckardt KU. Anti-erythropoietin antibodies and pure red cell aplasia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:398-406. 14747386.

Figure┬Ā1

Bone marrow biopsy (A) and aspiration (B) samples showing normocellular, active granulopoiesis with markedly decreased erythroid cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ├Ś 400).

Table┬Ā1.

Summary of patients with acute hepatitis A complicated by both pure red-cell anemia and autoimmune hemolytic anemia

| Age/Sex | Area | Time to onset of anemia* | HbŌĆĀ (g/dL) | ALTŌĆĀ (IU/L) | TBŌĆĀ (mg/dL) | Treatment of anemia | Outcome | Other feature | YearŌĆĪ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfusion | Therapy (Initial dose, duration) | |||||||||

| 21/F | The United States of America | 3 weeks | 5.3 | 789 | 20.9 | Yes | PDL (1.5 mg/kg, 11 weeks), IVIG (1 g/kg, 2 days), cyclosporin A (5 weeks) | recovery | FH, PBV19┬¦ | 2002 [11] |

| 55/F | Japan | 3 weeks | 3.6 | 9,605 | 31.6 | Yes | PDL (1 mg/kg, 16 weeks) | recovery | FH | 2009 [12] |

| 36/M | Korea | 3 weeks | 4.8 | 3,558 | 3.8 | Yes | PDL (1 mg/kg, 11 weeks) | recovery | AKI | 2011 [4] |

| 49/F | Korea | 3 weeks | 4.7 | 7,451 | 32.3 | Yes | PDL (1 mg/kg, 12 weeks) | recovery | None | Present case |

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print