Acute hepatitis C virus infection: clinical update and remaining challenges

Article information

Abstract

Acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a global health concern with substantial geographical variation in the incidence rate. People who have received unsafe medical procedures, used injection drugs, and lived with human immunodeficiency virus are reported to be most susceptible to acute HCV infection. The diagnosis of acute HCV infection is particularly challenging in immunocompromised, reinfected, and superinfected patients due to difficulty in detecting anti-HCV antibody seroconversion and HCV ribonucleic acid from a previously negative antibody response. With an excellent treatment effect on chronic HCV infection, recently, clinical trials investigating the benefit of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) treatment for acute HCV infection have been conducted. Based on the results of cost-effectiveness analysis, DAAs should be initiated early in acute HCV infection prior to spontaneous viral clearance. Compared to the standard 8–12 week-course of DAAs for chronic HCV infection, DAAs treatment duration may be shortened to 6–8 weeks in acute HCV infection without compromising the efficacy. Standard DAA regimens provide comparable efficacy in treating HCV-reinfected patients and DAA-naïve ones. For cases contracting acute HCV infection from HCV-viremic liver transplant, a 12-week course of pangenotypic DAAs is suggested. While for cases contracting acute HCV infection from HCV-viremic non-liver solid organ transplants, a short course of prophylactic or pre-emptive DAAs is suggested. Currently, prophylactic HCV vaccines are unavailable. In addition to treatment scale-up for acute HCV infection, practice of universal precaution, harm reduction, safe sex, and vigilant surveillance after viral clearance remain critical in reducing HCV transmission.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a global health concern and a major risk factor for cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), hepatic decompensation, and liver transplantation. Notably, the elimination of HCV by 2030 has been proposed a public health target by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. Although the global prevalence of HCV has decreased from 0.9% to 0.7% from 2015 to 2020 [2-4], there remains substantial geographical variation in its incidence rate.

While the gold-standard management for chronic HCV infection has been well established, there is yet a standardized management strategy for acute HCV infection. Considering the patients with acute HCV infection are at risk of progressive liver disease and may lead to further viral transmission, it is clinically crucial to develop an effective management strategy for this condition. In this review, we will summarize and discuss the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, therapeutic advances, and challenges for acute HCV infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

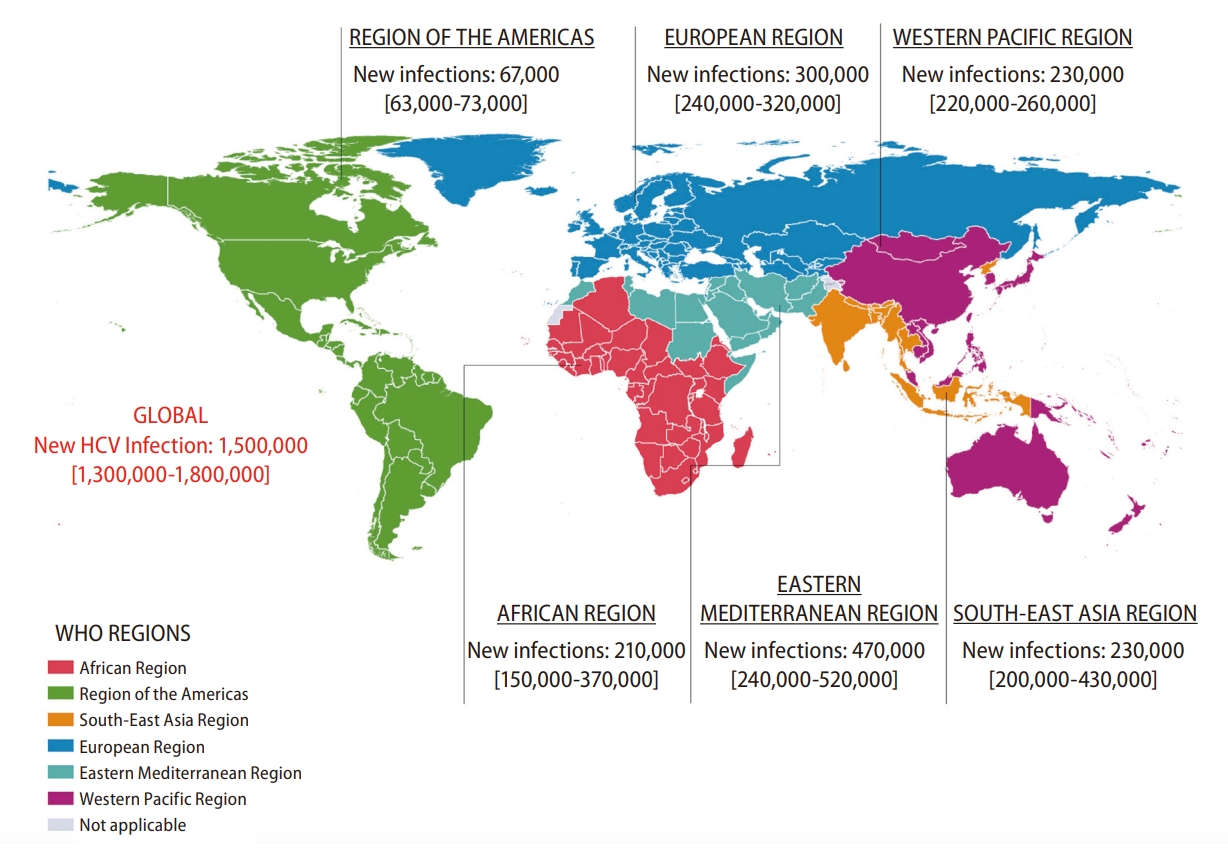

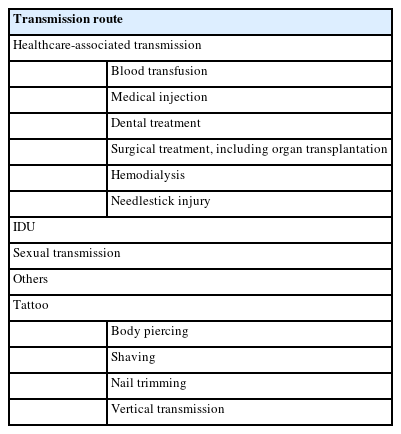

Precise real-world data on the incidence of HCV infection are only available in a limited number of countries, while some studies have attempted to estimate the rates of new HCV infection through modeling based on published data [5]. The incidence of HCV infection worldwide has reached its peak recently (Fig. 1) [6]. In 2019, the number of newly acquired HCV infection was reported to be 1.5 million per estimation by the WHO [7]. Although the global incidence of HCV infection has declined since the second-half of the twentieth century, evidenced by an annual decrease of about 250,000 cases during 2015–2019, there remains substantial geographical variations [8]. The East Mediterranean and European regions are noted with the highest rates of infection, accounting for 470,000 (62.5 per 100,000) and 300,000 (61.8 per 100,000) cases annually (Fig. 2) [7,8]. Table 1 shows the common parenteral routes of HCV transmission. In the East Mediterranean region, the most common routes of HCV transmission are unsafe invasive medical procedures, such as blood transfusion and injections. In the European region, particularly, Eastern Europe, injection drug use (IDU) accounts for a substantial proportion of HCV viral transmission. Furthermore, males account for around 54.6% of new HCV infections in 2019 [8].

People receiving unsafe medical procedures

Unsafe blood transfusion is not considered a major route of HCV transmission at a population level, since blood transfusion does not occur as common as other medical procedures, such as dental treatment. However, concerns for HCV infection via blood transfusion remain present in underdeveloped or developing regions or countries, where the prevalence of HCV is high and the quality of blood screening is suboptimal. The Global Disease Burden (GDB) estimated that the case number of new HCV infections resulted from unsafe medical injections ranged from 952,111 to 1,867,904 in 2000 and 157,592 to 315,120 in 2010 [9]. Additionally the decrease in the number of new HCV infections seemed correlated with the drop in event number of unsafe medical injections, which was 1.35 and 0.36 per year in 2000 and 2010, respectively [10]. However, the rate of injection device re-use is as high as 14% and 5% in East Mediterranean and South-East Asia, respectively, which raises the concerns about potential HCV transmission due to insufficient device sterilizations in these regions [11,12].

Dental visits and hemodialysis are highly associated with new HCV infections. Surveys conducted in Italy and Egypt have shown an odds ratio of acute HCV infection ranging from 1.5 to 3.7 in people who had undergone dental treatment [13-15]. The Dialysis Outcomes Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) has reported that the incidence of HCV in hemodialysis patients was 2.9 per 100 person-years (PYs) in 1996 and 1.2 per 100 PYs in 2015 [16]. Hemodialysis patients who are coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have been on dialysis for more than ten years, and stay in facilities with an HCV prevalence >20% are at a higher risk of acute HCV infection. Moreover, breaches in sanitary and disinfection practices, such as inadequate hand washing or gloves changing by medical staff before and after patient care, contamination of hemodialysis machine, and the use of shared medication requiring injection, may also contribute to viral transmission [17,18]. Although the incidence of HCV infection due to invasive medical procedures has decreased drastically in developed countries, the high incidence remaining in underdeveloped or developing countries suggest that there is still room for improvement in the universal practice of precaution against HCV.

People who inject drugs (PWID)

Of the estimated cases of newly contracted HCV infection in 2015, 23% were attributed to IDU. PWID may account for as high as 60% of newly contracted HCV infections in developed countries [19,20]. Specifically, young adults aged <30 (12.8–25.1 per 100 PYs) and those who have been incarcerated (5.5–31.6 per 100 PYs), show the highest incidence of HCV [21]. In young PWID, the risk of HCV contraction is highest (133 per 100 PYs) during the first year of IDU [22,23]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis enrolling 9,235 PWID from 28 studies yielded a sex difference in the risk of HCV contraction, with the pooled incidence rates being 20.36 per 100 PYs in females and 15.20 per 100 PYs in males (risk ratio: 1.36:1) [24]. Although such difference was suggested to be mainly associated with different behavioral and social risks among female and male PWID, the actual mechanisms remain elusive, with other potential mediators left largely unexamined.

Although the incidence of HCV in western Europe, Canada, and Australia has been relatively stable or declining, the number remains high or even increasing in the United States (US) and developing countries [25-29]. Data from the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) HCV surveillance indicated that HCV incidence has increased by 124% from 2013 to 2020. People who reported IDU comprised 66% of new HCV cases in 2020. Similar to the earlier annual reports, population aged from 20 to 39 had the highest incidence of acute HCV infection [29]. Shared use of syringes and drug preparation equipment, more frequent injections, having numerous injecting partners, particular injection drug types, having HIV coinfection, and low socioeconomic state are the key risk factors of HCV transmission among PWID [22,25,28,30].

People living with HIV (PLWH)

From 1990 to 2014, when interferon (IFN)-free direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) were unavailable, the CASCADE collaboration study, which recruited 16 cohorts across Europe, Canada, and Australia, found a lack of decline in HCV incidence among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) [31]. The GDB showed a trend of decreasing acute HCV infection in HIV-positive MSM after 2014, when patient education, mass screening, and scaled-up DAA treatment, were first implemented, particularly in Europe, Canada, and Australia. A meta-analysis summarizing reports between 2000 and 2019 on HIV-positive MSM revealed that the pooled incidence of HCV infection was 8.46 per 1,000 PYs. Although the pooled incidence of HCV infection was 0.12 per 1,000 PYs in HIV-negative MSM not on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), the incidence increased to 14.80 per 1,000 PYs in those on PrEP [32]. Different from the aforementioned risk factors for acute HCV infection in PWIDs, more frequent high-risk sexual behaviors, including unprotected anal intercourse, group sex, having multiple sex partners, sharing sex toys, and recreational drug use, were found to be the major risk factor for HCV infection in HIV-positive MSM [33-36].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

After exposure to HCV, there is a window of one to two weeks before serum HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) becomes detectable. In patients who develop symptoms, the incubation period between exposure and symptom onset ranges from 2 to 12 weeks. Approximately 80% of people with acute HCV infection do not exhibit symptoms. The remaining 20% may exhibit fever, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dark urine, and jaundice [37,38]. Because the symptoms are usually mild and non-specific, a diagnose of HCV infection is difficult during the acute phase. The elevation of serum alanine transaminase (ALT), an indicator of hepatic injury, typically occurs later than four weeks after viral exposure. Fulminant hepatitis and acute liver failure rarely occur in people with acute HCV infection [39]. However, the JFH1, a cell-culture-grown HCV genotype (GT) 2a virus, has been found in a Japanese patient with fulminant HCV infection [40-42].

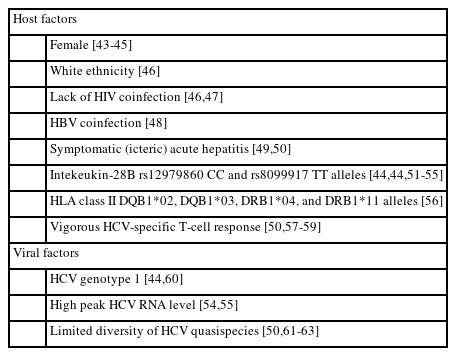

During the acute phase of HCV infection, serum HCV RNA and ALT levels may have significant fluctuations. About 80% of people with acute HCV infection will develop chronic infection, generally defined as the persistence of viremia for more than six months [2]. Various host and viral factors, including gender, race, HIV or HBV coinfection, presentation of jaundice, interleukin-28B polymorphism, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II alleles, HCV-specific T cell response, viral genotype, peak HCV RNA level, and diversity of viral quasispecies, may affect the course and outcome of acute HCV infection (Table 2) [43-63]. The period between viral exposure and seroconversion consists of three phases: (1) the preramp-up phase (2–14 days after exposure), with intermittent low or below-detection level of HCV RNA; (2) the ramp-up phase (the next 8–10 days following the first phase), with an exponential increase of serum HCV RNA levels; (3) the plateau phase (45 to 68 days following the second phase), with stable serum HCV RNA levels [55,64]. Although none of the aforementioned host or viral factors can accurately predict spontaneous resolution, assessing the dynamics of HCV RNA levels during the early phase of infection may help discriminate the development of acute resolving hepatitis or chronic infection [65]. Cases who experience viral rebounds or persistent viral plateau (<1 log10 IU/mL decline in HCV RNA levels following peak) after prior partial viral control (≥1 log10 IU/mL decline in HCV RNA levels following peak) are more likely to develop chronic infection. In contrast, people with significant viral decline after the plateau phase confer spontaneous HCV clearance [55]. Studies have suggested that the cumulative frequencies of acute resolving HCV infection were 80%, 90%, and 100% in patients who reached HCV RNA clearance at months 3, 4, and 5 of disease onset, respectively [66,67]. In PLWH with acute HCV infection, those whose serum HCV RNA levels did not reduce for ≥2 log10 at week 4 of diagnosis or remained detectable at week 12 of diagnosis were at a high risk of chronicity [68].

Superinfection refers to a primary infection of HCV followed by a secondary infection with a distinct HCV strain at a later time point [69]. Case reports have demonstrated that HCV superinfection may occur in chimpanzees and humans, including PWID, PLWH, organ transplant recipients, and people who receive multiple transfusion or endoscopic examinations [70-75]. Fluctuating or persistently elevated ALT levels and/or hepatitis flares may be observed during HCV superinfection [69,76]. As compared to the relatively benign clinical course in individuals with acute HCV monoinfection, HCV superinfection in patients with chronic HBV infection may result in more aggressive liver diseases [77]. This is particularly relevant in HBV endemic areas, such as Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and South America. Studies have indicated that acute HCV infection in HBV carriers may carry a significant risk of developing fulminant or subfulminant hepatitis. In a series of 93 HBV carriers who were superinfected with HCV, the proportions of patients with hepatic decompensation, hepatic failure and mortality were 34%, 11% and 10%, respectively [78].

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of acute HCV infection remains challenging since the gold-standard criteria have not been well-established. Generally, acute HCV infection is defined as the 6-month time period after the initial exposure to HCV. Anti-HCV antibody seroconversion provides direct evidence for HCV contraction, but the window period varies significantly (Table 3). Typically, it takes about 7 to 8 weeks for third-generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA-3) and 9 to 10 weeks for EIA-2 to detect anti-HCV antibodies from the initial HCV exposure [79]. However, the time to anti-HCV antibody seroconversion may be as long as 12 months or even absent, in PLWH, hemodialysis patients, or patients undergoing organ transplantation [80-82]. In these cases, HCV RNA testing become necessary. Moreover, since the anti-HCV antibody assay may have shown positive results at the first visit for most patients, it would be difficult to detect anti-HCV antibody seroconversion if past data about the patients’ anti-HCV antibody status are not available.

Other clinical features suggesting acute HCV infection include marked elevation of serum ALT levels (>5–20 times of the upper limit of normal), presentation of symptoms mentioned above, and known or possible exposure to HCV during the past six months (Table 3). However, the ALT elevation is not specific, and only 20% of patients are symptomatic. Furthermore, self-reported information of potential source/route of exposure is largely unreliable [37].

For patients with HCV reinfection after spontaneous viral clearance or a course of successful antiviral treatment, documentation of anti-HCV seroconversion would be impossible because the anti-HCV antibodies may persist for years following eradication of HCV [83]. Although testing for serum HCV RNA level may help assess viral resurgence, it is not common to monitor serum HCV RNA level after the patients have achieved sustained virologic response at off-therapy week 12 (SVR12), unless an abrupt increase in serum ALT levels is present during the follow-up. In addition, discriminating reinfection from late relapse requires identification of different viral strains through phylogenetic mapping, which cannot be performed without serum samples acquired during the prior episodes of infection and sufficient laboratory techniques.

Diagnosing HCV superinfection in individuals with chronic HCV infection is even more challenging than HCV reinfection due to the need of extensive longitudinal sequence analysis to show the dynamic evolution of viral strains over time. As it is difficult to confirm HCV superinfection, the true incidence and prevalence of HCV superinfection in chronic HCV infection, as well as the clinical consequences, remain largely unknown.

TREATMENT WITH IFN-FREE DAAs

The SVR24 rates of pegylated IFN (PEG-INF) with or without ribavirin (RBV) for 8 to 24 weeks in acute HCV infection range from 60% to 93% [84-90]. Although the antiviral response rates are fair with IFN-based therapies in patients with acute HCV infection, IFN is obsolete after the introduction of DAAs owing to the concerns about treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) and the longer treatment duration.

Clinical trials

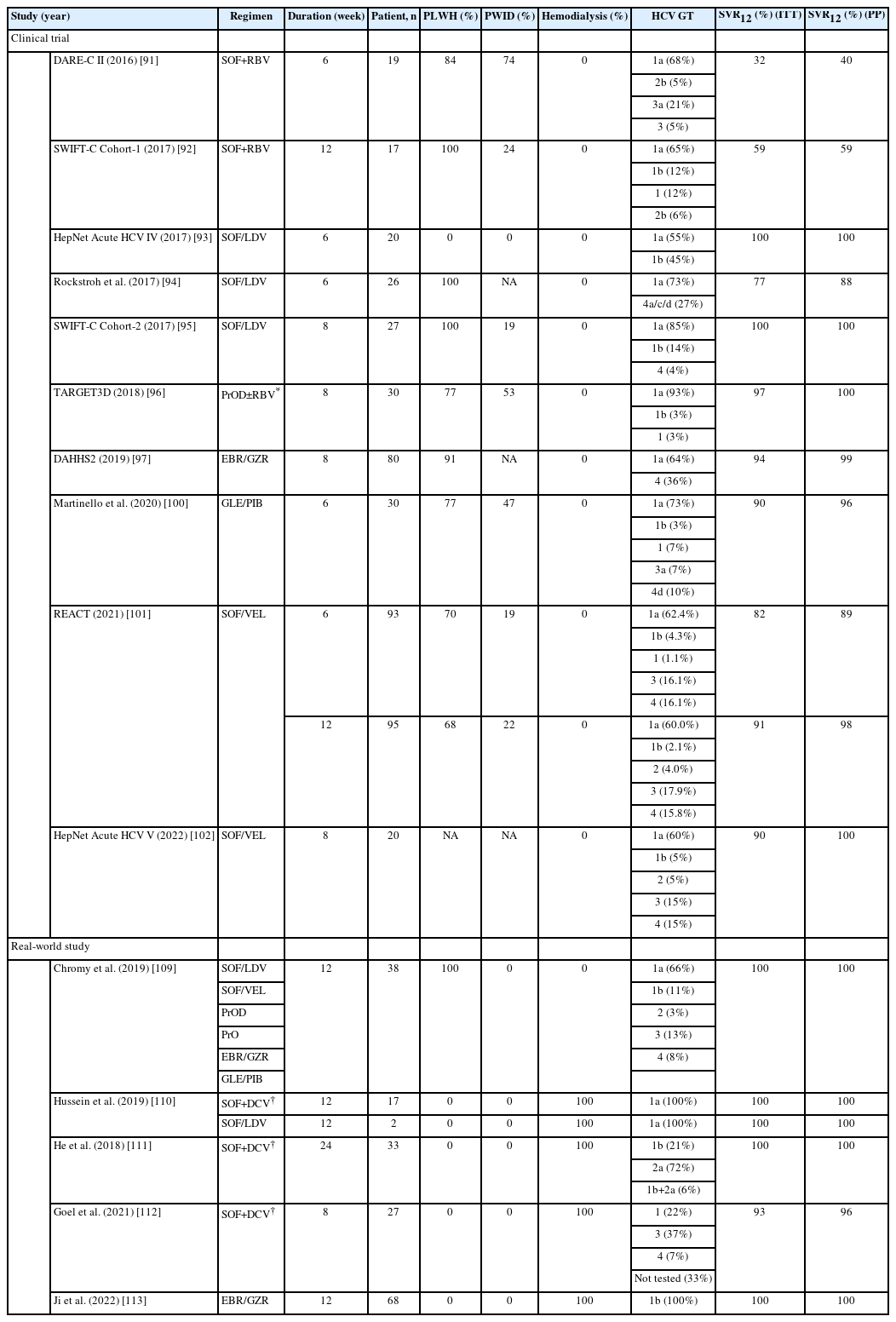

Sofosbuvir (SOF) plus RBV is the first US food and drug administration (FDA)-approved IFN-free DAA regimen for chronic HCV infection. The DARE-C II study treated 19 patients with acute HCV infection, among which 84% and 74% were PLWH and PWID, with SOF plus RBV for six weeks. However, the SVR12 rates by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses were 32% and 40% [91]. The SWIFT-C Cohort-1 study tried to extend the treatment duration of SOF plus RBV to 12 weeks in 17 PLWH with acute HCV infection. Although the SVR12 rate increased from 32% to 59%, SOF plus RBV was not recommended for acute HCV infection because the response rate was far from ideal (Table 4) [92].

The HepNet Acute HCV IV trial recruited 20 low-risk general patients with acute HCV GT1 or GT4 infection who received sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) for six weeks. All patients tolerated the treatment well, and the SVR12 rate was 100% [93]. Based on the promising result, Rockstroh et al. [94] tested this regimen on PLWH with the same condition as mentioned above. However, the SVR12 rates by ITT and PP analyses were 77% and 88%. Patients with a baseline viral load >6.96 log10 IU/mL tended to have a higher risk of relapse with six weeks of SOF/LDV [94]. The SWIFT-C Cohort-2 study extended the treatment duration of SOF/LDV to eight weeks in 27 PLWH, and they all achieved SVR12 [95]. Based on these trial results, SOF/LDV for six weeks is sufficient for non-HIV-positive patients with acute HCV GT1 or GT4 infection, while the treatment duration should be extended to 8 weeks for HIV-positive patients to secure a satisfactory SVR12 rate (Table 4).

In the TARGET3D trial, 30 patients with acute HCV GT1 infection received paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (PrOD) for eight weeks. RBV was added to PrOD in patients with HCV GT1a or unsubtypable GT1 infection. Seventy-seven percent and 53% of them were PLWH and PWID. All patients, except for one who discontinued treatment early, achieved SVR12 [96]. Eighty patients with acute HCV GT1 or GT4 infection who received elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBR/GZR) for eight weeks were recruited in the DAHHS2 trial. Most patients (91%) were PLWH. The SVR12 by ITT and PP analyses were 94% and 99%, respectively (Table 4) [97].

Current international guidelines recommend pangenotypic DAA regimens, including glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (GLE/PIB) and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL), as the first-line treatment for chronic HCV infection [98,99]. Treating patients with acute HCV infection with pangenotypic DAAs may be more beneficial than using genotype-specific DAAs because (1) HCV genotyping may not be reliable or possible when the HCV viremia is low during the acute phase of infection; (2) HCV genotyping may not be accessible or available in resource-limited regions; (3) By skipping HCV genotyping, patients may start to receive treatment earlier with the use of pangenotypic DAAs. Martinello et al. [100] conducted a multicenter, international trial to treat 30 patients with recent HCV infection with GLE/PIB for six weeks. Among these patients, 77% and 47% were PLWH and PWID. The SVR12 rate was 90% by ITT analysis. Among the three patients who failed to achieve SVR12, only one had confirmed virologic failure, and the SVR12 by PP analysis was 96% [100]. The REACT trial is a multicenter, international, non-inferior, randomized trial to compare the efficacy of SOF/VEL for 6 or 12 weeks in patients with recent HCV infection [101]. About 68% to 79% of patients were PLWH, and 19% to 22% were PWID. By ITT analysis, the SVR12 rates in the 6-week and 12-week arms were 82% and 91% (95% confidence interval: -18.6% to 1.0%), demonstrating a low response rate in the truncated arm by failure to meet the -12% non-inferior confidence bound. The SVR12 rates in the 6-week and 12-week arms were 89% and 98% by PP analysis. The HepNet Acute HCV V trial, which recruited 20 patients on HIV PrEP or opioid agonist therapy (OAT), extended the treatment duration of SOF/VEL to 8 weeks for acute HCV infection. Eighteen of 20 (90%) patients achieved SVR12, and the remaining two were lost to follow-up (Table 4) [102].

Real-world studies

Limited real-world studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of DAAs for low-risk general patients with acute HCV infection. Furthermore, most of those studies were case reports or case series, although the SVR12 was achieved in all patients [103-108]. Chromy et al. [109] retrospectively assessed 38 PLWH with acute HCV infection treated with various DAA regimens. All cases received 12 weeks of treatment and achieved SVR12. Four cohort studies have reported that the SVR12 rates in hemodialysis patients with acute HCV infection receiving SOF plus daclatasvir (DCV) for 8–24 weeks, SOF/LDV for 12 weeks, or EBR/GZR for 12 weeks ranged from 93% to 100% (Table 4) [110-113].

Treatment of HCV reinfection

In low-risk general patients with HCV who achieve SVR12 with antiviral treatment, the risk of HCV reinfection ranges from 0.14 to 0.185 per 100 PYs [114-116]. In PLWH, the risk of HCV reinfection was much higher (3.76 per 100 PYs) according to a recent meta-analysis. PLWH MSM and those with recent drug use had an incidence of reinfection of 6.01 and 5.49 per 100 PYs, respecitvely [117]. In PWID, the risk of HCV reinfection in those with recent drug use, IDU, and those receiving OAT were 5.9, 6.2, and 3.8 per 100 PYs, respectively [118]. While the global incidence of new HCV infection in hemodialysis patients was 1.2% in 2015, a recent survey in Taiwan indicated that the risk of HCV reinfection in hemodialysis patients was 0.23 per 100 PYs following the implementation of mass screening, treatment scale-up, and universal precaution [115]. A national survey in Australia has demonstrated an increasing number of HCV reinfection from 2016 to 2020 in patients who had achieved SVR12 with DAAs, which entails the importance of early diagnosis and timely treatment for HCV reinfection to reduce viral transmission [119].

Data regarding the effectiveness of DAAs in treating HCV reinfection in patients who have achieved SVR12 after a prior course of DAAs are limited. The REACH-C cohort assessed the effectiveness of treatment with GLE/PIB, SOF/VEL, SOF/LDV, SOF/DCV, EBR/GZR, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (SOF/VEL/VOX) in 88 Australians with HCV reinfection who achieved SVR12 with a previous course of DAAs. All patients were PLWH, PWID, incarcerated, or on OAT. The SVR12 rate in the 56 patients with available outcomes was 95%, which was comparable to the 95% response rate observed in DAA-naïve patients. Eight patients were treated using the same regimen as their prior treatment, and they all achieved SVR12 [120]. Liu et al. [121] recruited 22 Taiwanese patients diagnosed with HCV reinfection after DAA-induced SVR12. Eighteen (81.8%) of them were PLWH. Twenty patients started retreatment with pangenotypic GLE/PIB or SOF/VEL, and all achieved SVR12. Similar to the REACH-C report, all eleven patients, who were retreated with the same DAA regimen as the prior treatment, achieved SVR12 [121].

Treatment of HCV superinfection

Data regarding the use of DAAs in managing chronic HCV-infected patients with HCV superinfection are lacking. Based on the potential genotype switch and the presence of mixed viral strain infection in patients with HCV superinfection, pangenotypic DAA regimens are the preferred treatment choices to secure satisfactory viral eradication.

Treatment of acute HCV infection in patients undergoing organ transplantation

While the rates of solid organ donation and transplantation have increased over the last decade, the demand is still far greater than the supply, necessitating more efficient organ procurement and allocation. HCV-aviremic recipients are conventionally not recommended to receive HCV-viremic organs since HCV transmission occurs immediately after transplantation, and the recipients may develop lethal fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis if the acute HCV infection is left untreated [122-124]. In contrast to IFN, which has poor efficacy and patient tolerance, the excellent effects of DAAs on solid organ recipients with chronic HCV infection has garnered great interest in the application of prophylactic or pre-emptive DAAs to prevent or eradicate HCV transmission in this clinical condition.

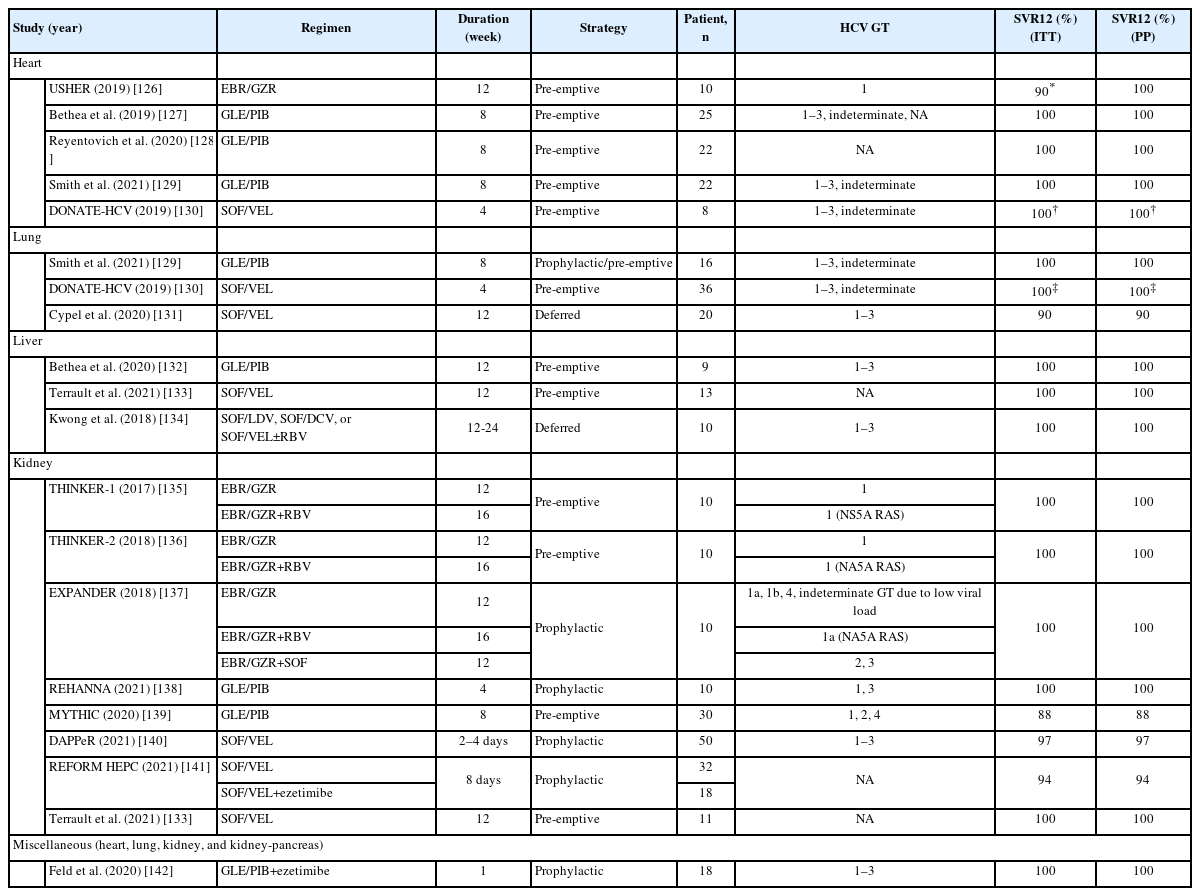

Numerous clinical trials and real-world studies have reported the experiences of using DAA treatment, either prophylactically, pre-emptively, or deferred, to manage post-transplant acute HCV infection in HCV-negative patients who have received solid organ transplant from HCV-viremic donors. Although the regimens and treatment durations vary widely across studies, a meta-analysis, which included 852 solid organ recipients from 35 studies, revealed that nearly all patients achieved SVR12. All seven recipients who relapsed after initial DAA treatment achieved SVR12 with a second course of rescue regimens. As HCV was eradicated during the early phase of acute HCV infection, there were no recipient deaths or graft loss [125]. Table 5 summarizes the representative trials that used DAA treatment to manage acute HCV infection in HCV-negative patients receiving HCV-viremic solid organs [126-142]. In general, the SVR12 rates were 100% when DAAs were administered for the same duration as indicated for chronic HCV infection. In addition, the SVR12 rate, excluding non-virologic failures, can reach >94% if the solid organ recipients received prophylactic or pre-emptive DAAs for more than one week.

Summary of IFN-free direct-acting antivirals for acute HCV infection after solid organ transplantation from HCV-viremic donors to HCV-aviremic recipients

Transplanting HCV-viremic organs to HCV-negative recipients has complex ethical and legal implications because of the intentional transmission of an infectious agent to the recipients. Although this approach provides benefits such as reduced wait time for organ transplant and reduced mortality while on the organ waiting list, these should be weigh against other risks such as HCV transmission from donors to recipients and from recipients to partners, progressive hepatic and extrahepatic diseases in case of DAA failures, and graft loss before making clinical decisions. Most importantly, the local legal regulations must be considered.

Cost-effectiveness of early DAA treatment

Using a willingness-to-pay threshold of USD 100,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY), timely DAA treatment for acute HCV infection was cost-effective with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of USD 19,991 per QALY for patients not at risk of HCV transmission. Furthermore, DAA treatment for acute HCV infection in patients at risk of HCV transmission was cost-saving, with an increase of QALYs by 0.03 and a decrease of costs by USD 3,655 [143]. The cost-effectiveness analysis of prophylactic or pre-emptive DAAs in HCV-negative patients who receive HCV-positive organs remains to be examined.

Timing of treatment initiation

There has not been a consensus on the timing of therapeutic intervention for people with acute HCV infection. The possibility of spontaneous viral clearance, the benefits of early treatment initiation (based on the cost-effectiveness of universal DAA treatment), and the risk of HCV transmission as well as potential morbidity/mortality if no treatment is provided, should be considered before treatment initiation for patients with acute HCV infection.

According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Disease Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines, DAA treatment should be given once acute viremic HCV infection is confirmed [98,99,144]. While the AASLD guidelines suggest treating acute HCV infection with the same DAA regimens as recommended for chronic HCV infection, the EASL guidelines suggest using GLE/PIB or SOF/VEL for eight weeks to manage acute HCV infection. Although PrEP can significantly reduce HIV transmission, PrEP or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) with DAAs is not recommended in this clinical condition due to the lack of evidence [99,144,145].

The timely diagnosis and early intervention for acute HCV infection are relevant to HCV-negative patients receiving HCV-viremic organs. Pangenotypic DAAs, such as GLE/PIB or SOF/VEL for 12 weeks, should be initiated within two weeks of transplantation if the recipients are clinically stable. Prophylactic or pre-emptive treatment with pangenotypic DAAs is also recommended in this patient group [99,144]. However, the ideal pangenotypic regimens remain debatable, as AASLD/IDSA and EASL guidelines have proposed different regimens.

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Since the gold-standard diagnostic criteria for acute HCV infection has not been well-established, to detect de novo infection, reinfection, or superinfection of HCV promptly, clinicians should stay alert to this potential diagnosis, particularly when encountering patients with markedly elevated ALT levels and/or risk factors of HCV transmission. While the guidelines recommend initiating DAA treatment over waiting for spontaneous viral clearance in managing acute HCV infection, it is important to note the DAA regimens are not yet licensed to treat acute HCV infection. Furthermore, the discrepant pricing and payment policies across countries may hinder the universal and early access to DAA treatment. In addition to early identification and timely therapeutic intervention, public health strategies, such as universal precaution, harm reduction, safe sex, and post-SVR12 viral surveillance, should also be implemented to efficiently reduce the risk of HCV transmission [146].

With the high HCV infection rates observed in endemic areas and in high-risk PWID and PLWH, development of prophylactic vaccines against HCV should be prioritized to combat HCV transmission. Despite years of vigorous work, only two candidate vaccines have advanced to human studies. The first one consists of the recombinant full-length E1/E2 glycoprotein of HCV GT1a with an oil-in-water adjuvant (MF59C.1) [147]. This vaccine did not enter further efficiency studies due to failure in generating antibodies that neutralized heterologous HCV pseudo-particles in study volunteers. The second vaccine consists of a chimpanzee adenovirus vector (ChAd3) as prime and a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vector as boost, both of which encode the HCV GT1b non-structural proteins (NS). This vaccine was tested in phase 1–2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in PWID. Although it generated strong HCV-specific T-cell responses and lowered the peak HCV RNA level, it cannot prevent chronic HCV infection [148]. Recently, a bivalent pangenotypic prophylactic vaccine, which consists of a chimpanzee adenovirus vector (ChAdOx1) encoding conserved sequences across HCV GT1-6 and a modified HCV glycoprotein E2 with deletions of hypervariable regions (HVR) 1 and 2, has successfully induced both neutralizing antibody and CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response in mice experiments [149]. Further translational research is needed to confirm this new candidate’s clinical effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

Acute HCV infection remains a threat to global health, despite a decrease of incidence over the past decades. Transmitted through parenteral routes, new cases of HCV infection comprise mainly of people receiving unsafe medical procedures, PWID, and PLWH.

Diagnosing acute HCV infection can be challenging, particularly in immunocompromised, reinfected, and superinfected patients, since it is difficult to detect anti-HCV antibody seroconversion and confirm the presence of HCV RNA from a previously negative antibody response. Therefore, both comprehensive history taking and prudent laboratory assessment are needed in order to more accurately diagnose new cases.

To date, numerous clinical trials and real-world cohort studies have supported the role of DAAs in managing acute HCV infection. Furthermore, early initiation of DAA treatment was found to be cost-saving and cost-effective in patients with acute HCV infection, regardless of the risk of HCV transmission. Although the efficacy of DAAs in treating acute de novo HCV infection and HCV reinfection is excellent, there is not yet a consensus on the optimal DAA regimens and the duration of treatment. In HCV-negative recipients who have received HCV-viremic organs, the transmission of HCV from donors to recipients typically happens within a few days of transplantation. With a well-defined timing and route of HCV transmission, the administration of prophylactic or pre-emptive DAAs during the peri-transplant period almost always eradicate HCV in the organ recipients, although the optimized DAA regimens and treatment duration remain to be determined. Overall, treatment of acute HCV infection with DAAs can improve patient outcomes and reduce HCV transmission. Prophylactic vaccines against HCV are not yet available, and a pangenotypic HCV vaccine is under active development. Patient education and public health practices, such as universal precaution, harm reduction, safe sex, and vigilant post-SVR12 surveillance, may help achieve the WHO goal of HCV eradication by 2030.

Notes

Authors’ contribution

Conception and design: CH Liu, JH Kao; Drafting of the article: CH Liu, JH Kao; Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: CH Liu, JH Kao; Final approval of the article: CH Liu, JH Kao; Administrative, technical, or logistic support: JH Kao; Collection and assembly of data: CH Liu.

Conflicts of Interest

Chen-Hua Liu: advisory board for Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme; speaker’s bureau for Abbott, Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme; research grant from Abbvie, Gilead Science, Merck Sharp & Dohme. Jia-Horng Kao: advisory board for Abbott, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche; speaker’s bureau for Abbott, Abbvie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hui-Ju Lin and Pin-Chin Huang for managing the administrative affairs; the 7th Core Lab of the National Taiwan University Hospital, and the 1st Common Laboratory of the National Taiwan University Hospital, Yun-Lin Branch, for the technical support; Jo-Hsuan Wu for polishing the manuscript writing.

Abbreviations

HCV

hepatitis C virus

PWID

people with inject drugs

PLWH

people living with human immunodeficiency virus

DAA

direct-acting antiviral

SVR

sustained virologic response

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

WHO

World Health Organization

IDU

injection drug use

GDB

global disease burden

DOPPS

Dialysis Outcomes Practice Patterns Study

PY

person-year

IFN

interferon

HBV

hepatitis B virus

HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

CDC

Center for Disease Control

MSM

men have sex with men

PrEP

pre-exposure prophylaxis

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

HLA

human leukocyte antigen

EIA

enzyme immunoassay

PEG-IFN

pegylated interferon

RBV

ribavirin

AE

adverse event

SOF

sofosbuvir

FDA

food and drug administration

ITT

intention-to-treat

PP

per-protocol

LDV

ledipasvir

GT

genotype

PrOD

paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir

EBR

elbasvir

GZR

grazoprevir

GLE

glecaprevir

PIB

pibrentasvir

VEL

velpatasvir

OAT

opioid agonist therapy

DCV

daclatasvir

VOX

voxilaprevir

QALT

quality-adjusted life year

AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

IDSA

Infectious Disease Society of America

EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

PEP

post-exposure prophylaxis

ChAd

chimpanzee adenovirus

MVA

modified vaccinia Ankara

NS

nonstructural protein

HVR

hypervariable region