The effects of moderate alcohol consumption on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Article information

Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is accepted as a counterpart to alcohol-related liver disease because it is defined as hepatic steatosis without excessive use of alcohol. However, the definition of moderate alcohol consumption, as well as whether moderate alcohol consumption is beneficial or detrimental, remains controversial. In this review, the findings of clinical studies to date with high-quality evidence regarding the effects of moderate alcohol consumption in NAFLD patients were compared and summarized.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic liver disease characterized by serial progression from isolated steatosis to steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis [1]. NAFLD is associated with the metabolic conditions of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity [2]. Mirroring the obesity epidemic, the global prevalence of NAFLD among adults is estimated to be 23–25%, and has become a major global concern as a dominant cause of chronic liver disease with increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes [3–5]. In particular, as the proportion of young patients is increasing, the burden of disease is expected to rise, and long-term management strategies are needed [6,7].

NAFLD is defined as hepatic steatosis occurring in over 5% of hepatocytes without excessive use of alcohol, viral hepatitis, or autoimmune liver disease. NAFLD is considered the counterpart of alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD) [8-10]. NAFLD and ARLD share a common pathophysiological basis involving gut dysbiosis and subsequent changes. In addition, single nucleotide polymorphisms in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3), transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7 (MBOAT7), and 17-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 13 gene (HSD17B13) are significant genetic risk factors for NAFLD and ARLD [11-15]. These two entities are difficult to distinguish because both histologically include a certain degree of steatosis, lobular inflammation, and ballooning [16]. However, NAFLD and ARLD are distinguished by excessive alcohol consumption based on history taking and questionnaires, however, the amount of safe alcohol consumption accepted as “non-alcoholic” is disputed. In previous studies, conflicting evidence on whether moderate alcohol consumption is protec tive or detrimental for development of NAFLD was reported [17,18].

In this review, the clinical results to date on the effects of moderate alcohol consumption in NAFLD patients were compared and summarized.

DEFINITIONS FOR MODERATE ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

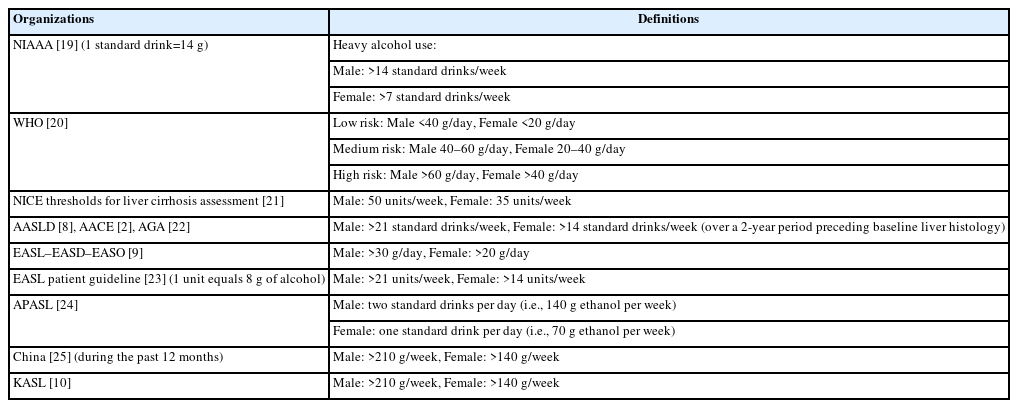

The effects of alcohol on patients appear over a long period of time, and because randomized control trials are difficult to perform, the effects can only be estimated using observational studies. Several definitions for significant alcohol consumption to date exist (Table 1).

The definition of moderate alcohol consumption adopted by most guidelines and previous studies is <21 units of alcohol per week for males and <14 units of alcohol per week for females. Some researchers adopt other definitions based on their needs [26-28], however, many experts recommend the above definition for comparison and objectivity of studies [29,30]. One unit of alcohol is usually 10 mL of pure alcohol but standard drink definitions vary worldwide from 8–20 g of alcohol [31]. Therefore, the definition used should be confirmed when reviewing previous research.

DETERMINING WHETHER MODERATE ALCOHOL DRINKING IS BENEFICIAL OR DETRIMENTAL

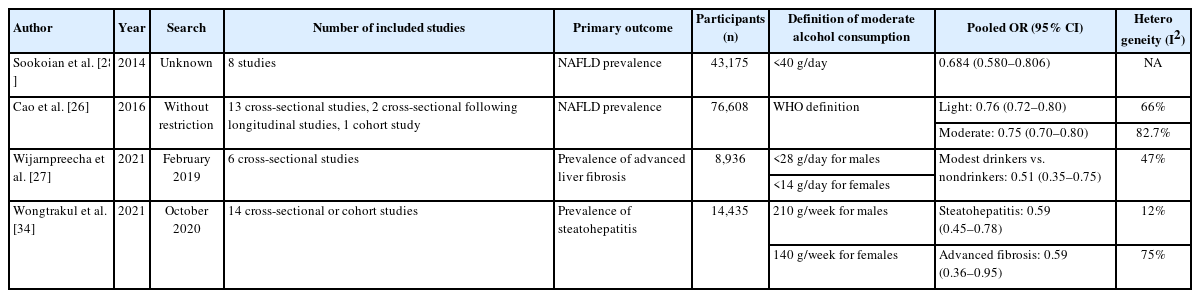

Although alcohol is a carcinogen with a well-known doserisk relationship [32,33], meta-analyses based on many previous studies have published results that moderate alcohol consumption showed a protective effect against NAFLD (Table 2).

Comparison of previous meta-analyses in which the effects of moderate alcohol consumption in NAFLD patients were assessed

Notably, Sookoian et al. [28] suggested that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a significant protective effect against NAFLD (Table 2). Body mass index (BMI) was not a statistically significant confounding factor in meta-regression analysis (slope=0.01, P<0.44) but moderate alcohol consumption was more protective in women than men (53% in women, 30% in men). This result was consistent with the odds of having steatohepatitis (odds ratio [OR]=0.501, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.340–0.740, P<0.0005, I2=0%) without heterogeneity [28]. Cao et al. [26] showed similar results. In pooled ORs for the prevalence of NAFLD, low- and moderaterisk alcohol consumption consistently showed a protective effect regardless of sex or BMI (≥25 vs. <25). A similar conclusion was presented in a recent meta-analysis. The risk of alcohol consumption in advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD was evaluated in recent meta-analyses. In Wijarnpreecha et al. [27] and Wongtrakul et al. [34], moderate alcohol consumption was associated with a lower risk of advanced fibrosis and steatohepatitis with lower-to-intermediate heterogeneity, although their definitions of alcohol consumption differed (Table 2). Furthermore, NAFLD patients with moderate alcohol consumption had a lower mortality risk than lifelong abstainers (hazard ratio [HR]=0.85, 95% CI: 0.75–0.95, I2=64%).

Despite the above results, alcohol consumption does not guarantee a protective effect against the progression of cirrhosis [35-37]. In a large NAFLD cohort study in Korea, patients with low fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) progressed to intermediate or high FIB-4 with light alcohol drinking (<10 g/day, adjusted HR=1.06, 95% CI: 0.98–1.16) and moderate alcohol drinking (10 to <20 g/day for women, 10 to <30 g/day for men, adjusted HR=1.29, 95% CI: 1.18–1.40) [38]. In a recent NAFLD cohort study, moderate amounts of alcohol intake in NAFLD patients increased the risk of type 2 diabetes and of advanced fibrosis with the synergistic effect of insulin resistance [39,40]. The longitudinal association between moderate use of alcohol (≤2 drinks/day) and histology findings on follow-up liver biopsy more than 1 year apart were evaluated in a previous study; non-drinkers had a greater mean reduction in steatosis grade (0.49 reduction) than moderate drinkers (0.30 reduction, P=0.04) and moderate drinkers had significantly lower odds of steatohepatitis resolution compared with nondrinkers (adjusted OR=0.32, 95% CI: 0.11–0.92, P=0.04) [41].

Alcohol is also a well-known primary cause for developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [42,43]. In a previous meta-analysis, the dose-risk curve indicated a linear relationship with the amount of alcohol consumed, estimated excess risk of 46% for 50 g/day and 66% for 100 g/day [44]. Furthermore, in a meta-analysis, the risk of HCC was reported to decrease after alcohol cessation by 6% to 7% a year [45]. In another meta-analysis, Wongtrakul et al. [34] narrowed the analysis target to only NAFLD patients with moderate alcohol consumption, showing a significant HR of 3.77 (95% CI: 1.75–8.15, I2=0%) for developing HCC.

Several disadvantages should be considered when interpreting the conflicting research results discussed above. Previous meta-analyses had several inherent limitations due to the design of the included studies. Almost all studies were cross-sectional in design, thus limiting establishment of causality of the observed factors associated with selection bias and reverse causality issues [46]. Even if the researchers used a well-designed survey tool such as Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye, the results may be associated with recall bias. Population surveys can underestimate alcohol consumption by approximately 40–50% [47]. Drinking patterns as well as quantity can have an effect. For example, binge drinking affects lipid profile and liver function tests and aggravates liver fibrosis compared with non-binge drinking [48,49]. In several studies, moderate alcohol drinkers tended to have higher socio-economic status (SES) and were less obese than lifelong abstainers which may confound the association between alcohol consumption and NAFLD through interference from the interaction between NAFLD and obesity [50,51].

POTENTIAL CONFOUNDING FACTORS REMAIN UNMEASURED

Gut microbiota

Confounding factors may exist that are not identified through history-taking or blood tests in routine clinic visits. In recent studies, consumption of alcohol and alcohol produced by the gut microbiome were shown to affect development of NAFLD. When blood alcohol concentration increases without significant alcohol consumption, autobrewery syndrome can be suspected. Some microbiota, particularly Proteobacteria (especially Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli) can ferment dietary sugars into ethanol [52]. Engstler et al [53]. reported that patients with NAFLD, even children, have increased blood ethanol levels due to endogenously produced ethanol. Recently, Yuan et al. [54] found high-alcohol-producing K. pneumoniae (HiAlc Kpn) in the gut microbiome of up to 60% of NAFLD patients. When clinically isolated HiAlc Kpn was transferred into mice via fecal microbiota transplant, the recipient mice were observed to have NAFLD [54]. In another in vivo study using proteome and metabolome analyses, researchers showed that HiAlc Kpn catabolizes carbohydrates via the 2,3-butanediol fermentation pathway and a potential causative agent of NAFLD [55]. Therefore, the fecal microbiome in NAFLD patients should be considered a confounding factor.

Types of alcoholic beverages

Whether beer or wine is safer than liquor or distilled spirits regarding NAFLD has been questioned. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed the amount of alcohol consumed is the most influential factor rather than the type of alcoholic drink [56]. In a cross-sectional study utilizing data from the NHANES III conducted in the United States from 1988 to 1994, suspected NAFLD (alanine transaminase >43 IU/L) was observed in 3.2% and 0.4% among 7,211 nondrinkers and 945 moderate wine drinkers (alcohol consumption <10 g/day), respectively, and the adjusted OR was 0.15 (95% CI: 0.05–0.49) [57]. In a recent study in which the association between fibrosis and type and pattern of alcohol consumption in a biopsy-proven NAFLD cohort was evaluated, moderate (<70 g/week) alcohol consumption, particularly wine in a non-binge manner, was associated with lower fibrosis in NAFLD patients. In an animal study using a NAFLD mouse model fed a high-fat diet, extended-maceration wine improved glucose tolerance and reduced hepatic fat accumulation. Pomace also improved insulin sensitivity and reduced hepatic triglycerides [58].

Recently, a randomized controlled trial was announced to evaluate the effects of beer on human gut microbiota. Marques et al. recruited 22 healthy men in Portugal who were assigned to drink 1 can of alcoholic or non-alcoholic lager each day for 4 weeks. Intestinal microbial diversity improved as determined based on the Shannon index [59], indicating that drinking beer once a day can improve intestinal microbiome diversity regardless of alcohol content. That result is simultaneously consistent and contradictory to previous studies in which the effects of beer on the microbiome were investigated. In a study in Mexico, an increase in gut microbiome diversity, especially the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes, was observed in healthy men and women who consumed 355 mL of non-alcoholic beer a day for 30 days. However, the same improvement was not observed in a separate group who drank 355 mL of beer with 4.9% alcohol content [60]. The above positive effects of fermented alcoholic beverages are presumably due to polyphenols, although additional evidence is needed.

CONCLUSION

Clinical data have not conclusively proven the effects of moderate alcohol consumption and the amount of safe alcohol consumption for NAFLD patients has not been determined. Moderate alcohol consumption in patients with NAFLD has various effects and conflicting results have been reported. Unregulated factors such as sex, age, ethnicity, obesity, comorbidities, genetic factors, incomplete study design, unclear endpoints, economic and social aspects, and underreporting alcohol use confound the results. Based on the basic medical principle of “first, do no harm”, recommending moderate drinking to NAFLD patients, especially those with comorbid diseases or advanced liver fibrosis, is premature. Additional longitudinal studies are expected to demonstrate the interactions between moderate alcohol consumption, effect of type/pattern of alcohol use, and SES based on NAFLD stage.

Notes

Authors’ contribution

HO, WS, and YKC contributed to the design and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

ARLD

alcohol-related liver disease

BMI

body mass index

OR

odds ratio

CI

confidence interval

HR

hazard ratio

FIB-4

fibrosis-4 index

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

SES

socio-economic status

AUDIT

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

CAGE

Cut

HiAlc Kpn

high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

ALT

alanine transaminase