Hepatogastric fistula caused by direct invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization and radiotherapy

Article information

Abstract

A 63-year-old man with a history of hepatitis-B-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the left lateral portion of the liver received repeated transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) and salvage radiotherapy. Two months after completing radiotherapy, he presented with dysphagia, epigastric pain, and a protruding abdominal mass. Computed tomography showed that the bulging mass was directly invading the adjacent stomach. Endoscopy revealed a fistula from the HCC invading the stomach. Although the size of the mass had decreased with the drainage through the fistula, and his symptoms had gradually improved, he died of cancer-related bleeding and hepatic failure. This represents a case in which an HCC invaded the stomach and caused a hepatogastric fistula after repeated TACE and salvage radiotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer and is now the fifth most common cancer worldwide.1 In South Korea, HCC is the fourth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related death.2 With recent improvements in diagnostic and treatment strategies, survival of patients with HCC had been prolonged significantly.1 Consequently, the incidence of extrahepatic metastases by HCC is increasing, which currently accounts for 37~64% of all.1 Of various organs, the lung is the most common site for metastasis, followed by regional lymph nodes and bones.3 In contrast, metastasis to gastrointestinal (GI) tracts by HCC rarely occurs, being found in only 0.7 to 2% of all HCC patients.4-6 Previous case reports proposed that metastasis of HCC mainly occurred through direct invasion, hematogenous spread, or peritoneal seeding.3,5,7 Among them, direct invasion of HCC was known to be the most common route of metastasis to the GI tract.3,8,9 Although most metastases of HCC to the GI tract are incidentally found through imaging study or autopsy because of their asymptomatic presentation,9,10 hemorrhage from the GI tract is the most frequent manifestation in case of direct invasion to GI tract by HCC.7,11,12 In this report, we described a case of hepatogastric fistula caused by HCC after repeated transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and salvage radiotherapy with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

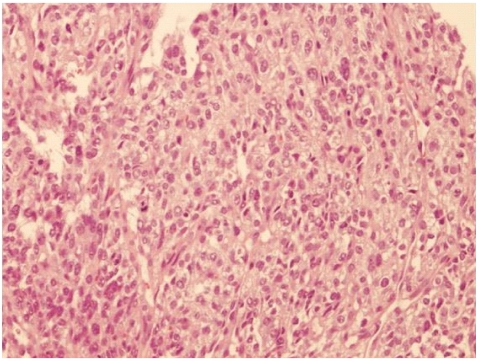

A 63-year-old man visited our institute, complaining of dysphagia and postprandial epigastric pain. Physical examination revealed palpable abdominal mass in the epigastric area and laboratory findings were not remarkable except high alkaline phosphatase (118 IU/mL) and bilirubin (1.6 mg/dL) levels. Two years ago, he was diagnosed as having hepatitis B virus-related HCC based on computed tomography (CT) and hepatic angiography results demonstrating two hepatic masses compatible with HCC (8.0×8.0 cm in segment III and 3.0×2.5 cm sized in segment VIII) with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein concentration of 50,202 IU/mL. Follow-up CT scan after three sessions of TACE revealed that HCC in the right lobe was completely filled with lipiodol, but HCC in the left lobe still showed viability in spite of size reduction. Thereafter, he was found with ruptured HCC in the left lobe and underwent additional three sessions of TACE. However, HCC in the left lobe did not respond to repeated TACE, but grew in size. Moreover, it also revealed additional suspicious features indicating direct invasion to the adjacent stomach wall on CT scan. Therefore, local salvage radiotherapy for HCC in the left lobe was administered using tumor dose of 4,500 cGy with a daily fraction of 180 cGy. In this visit with dysphagia and postprandial epigastric pain, two months after the end of radiotherapy, we noted that bulging HCC in the left lobe was still directly invading the adjacent stomach (Fig. 1). Upper GI endoscopy showed the opening of fistula to HCC which was covered with exudates (Fig. 2). Endoscopic biopsy through hepatogastric fistula revealed poorly differentiated HCC (Fig. 3). His symptoms were thought to be caused by extrinsic compression of the stomach by bulging HCC in the left lobe and we consulted with a surgeon for palliative resection. However, the resection could not be performed as the patient had poor liver reservoir (indocyanine green retention at 15 minutes [ICG 15], 39.1%). Two weeks later when he re-visited our institute for follow-up, he did not complain about previous symptoms of dysphagia and postprandial epigastric pain. Physical examination showed that the palpable abdominal mass considerably decreased, and CT scans also indicated marked reduced size of the bulging HCC with necrosis in the left lobe (Fig. 4). The patient was managed for three months in a conservative manner, and was referred to the emergency room of our institute with massive hematemesis. Emergency upper GI endoscopy confirmed cancer bleeding into the stomach via fistula. Because of incomplete hemostasis with argon plasma coagulation, he underwent emergency left gastric arterial embolization with successful hemostasis. However, his clinical course was unfavorable and finally he died of hepatic failure on the 14th day of admission.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed protrusion of a tumor into the gastric lumen and opening of a hepatogastric fistula.

The microscopic appearance of the interface between the gastric wall and the tumor was indicative of a poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×100).

DISCUSSION

Invasion of the GI tract by HCC is rare and is associated with poor prognosis. Chen et al. reported the first such case which occurred in 2% (8 out of 396 patients) during the course of disease with the median survival of one month (range, two to eight weeks) after the diagnosis.5 Lin et al. reported that 11 out of 2,237 patients (0.5%) with HCC showed the GI tract involvement, and none of them survived longer than nine months.13 Although the incidence of hepatogastric fistula in patients with HCC has not yet been reported in South Korea, prognosis after the diagnosis of hepatogastric fistula was grave with survival time of four months in our case.

The sites invaded by HCC were mainly the stomach, duodenum, and colon. Besides two case reports about colonic invasion by HCC14,15 and one case report on duodenal invasion HCC,10 there were a few case reports about gastric invasion by HCC in English language literature from Pubmed, limited to the past 30 years.7-9,11,16,17 The mode of metastasis was presumed to be hematogenous or direct invasion by contiguous neoplasm.3,5,11,13

Although most cases were asymptomatic, hemorrhage was frequent initial manifestation of direct invasion of HCC to the GI tract in previous reports.7,11,12 However, Yo et al indicated that gastric perforation was the initial manifestation of gastric invasion by HCC, not hemorrhage.16 In our patient, dysphagia and postprandial epigastric pain was the first presentation, and the symptoms disappeared with a sudden shrinkage of the protruding HCC on physical examination and CT scan. It might be attributable to the passage of necrotic materials associated with HCC through hepatogastric fistula. In addition to dysphagia and postprandial epigastric pain, GI tract hemorrhage also developed as a delayed complication four months after the diagnosis of hepatogastric fistula.

HCC invasion of the GI tract can be diagnosed based on radiologic and histologic proofs. Although endoscopic biopsy is still the mainstay method to detect GI tract metastasis in patients with HCC,13 Park et al suggested that hypervascular GI tract lesion on arterial-phase imaging similar to HCC could be one of the criteria used to document metastatic lesion rather than primary tumor of the GI tract.3 However, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate metastatic HCC in the GI tract from synchronous stomach cancer. This is particularly true where patients have documented HCC but lack available tumor tissue or have poorly differentiated tissue seen on endoscopic biopsy.3,13 In our case, hepatogastric fistula was confirmed by radiologic, endoscopic, and histologic examination.

Since HCC invasion of the GI tract is rare, the exact predisposing factors have not been known yet. Several factors with possible association with the development of such invasion have been suggested. Several reports suggested that direct invasion of HCC to the stomach had a tendency to develop in patients with a history of loco-regional treatment such as TACE or intra-arterial chemotherapy.5,14,15 Accordingly, it could be hypothesized that the mode of direct invasion might be initiated by the adhesion of exophytic HCC after loco-regional treatment. That is, TACE for such exophytic HCC might induce an inflammatory reaction in the contiguous GI tract, which causes the serosal side of GI tract to become adherent to tumor capsule.5,13 However, Park et al reported that seven out of 12 patients with direct invasion of GI tracts by HCC had no previous treatment, and assumed that the main factors for the direct invasion were growth pattern, tumor size, and location rather than a previous history of loco-regional treatment.3 In the current study, the patient was treated with repeated TACE and radiotherapy on huge, and exophytic HCC located in left lobe and the stomach was firmly attached to liver. All these factors might have contributed to direct gastric invasion by HCC and resulted in the formation of hepatogastric fistula.

Some viewed gastrointestinal fistula as a complication after radiofrequency ablation therapy,10,18,19 few reported about hepatogastric fistula formed by direct invasion of HCC to the stomach after repeated TACE and salvage radiotherapy. Recently, Wang et al reported a case of delayed spontaneous formation of hepatogastric fistula nine years after TACE and radiotherapy treatment.20

Although, as mentioned above, hepatogastric fistula formed by HCC invasion is rare, it should be considered in patients with huge and protruding HCC adjacent to GI tract. Patients should be investigated more carefully with extra attention, especially if they are scheduled for repeated TACE or radiotherapy as treatment for HCC closed to the GI tract. That is because complications such as fistula, hemorrhage, and perforation might develop, which could lead to rapid deterioration of liver function, limiting the chance of treatment, and eventually shortening the survival. HCC invasion of the GI tract is expected to become more common based on the recent increase in the incidence of HCC and more frequent utilization of TACE and radiotherapy to treat unresectable HCC.