Development and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with diabetes

Article information

Abstract

The incidence of diabetes mellitus and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been increasing worldwide during the last few decades, in the context of an increasing prevalence of obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Epidemiologic studies have revealed that patients with diabetes have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of developing HCC, independent of the severity and cause of the underlying liver disease. A bidirectional relationship exists between diabetes and liver disease: advanced liver disease promotes the onset of diabetes, and HCC is an important cause of death in patients with diabetes; conversely, diabetes is a risk factor for liver fibrosis progression and HCC development, and may worsen the long-term prognosis of patients with HCC. The existence of close interconnections among diabetes, obesity, and NAFLD causes insulin resistance-related hyperinsulinemia, increased oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation, which are assumed to be the underlying causes of hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with diabetes. No appropriate surveillance methods for HCC development in patients with diabetes have been established, and liver diseases, including HCC, are often overlooked as complications of diabetes. Although some antidiabetic drugs are expected to prevent HCC development, further research on the optimal use of antidiabetic drugs aimed at hepatoprotection is warranted. Given the increasing medical and socioeconomic impact of diabetes on HCC development, diabetologists and hepatologists need to work together to develop strategies to address this emerging health issue. This article reviews the current knowledge on the impact of diabetes on the development and progression of HCC.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and mortality of liver cancer have been continuously increasing during the last decades [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of primary liver cancer, develops in the context of chronic liver disease in 70–90% of the cases. The main causes of the underlying liver diseases are persistent infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol abuse [2,3]. However, in recent years, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its more active form, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), have emerged as new risk factors for HCC and are replacing viral-and alcohol-related liver diseases as major pathogenic promoters, particularly in developed countries [4]. NAFLD is a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome, which is strongly associated with overweight or obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a disease characterized by hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance, with a tremendous impact on human health worldwide. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that patients with diabetes have an increased risk of many kinds of cancer, including breast, pancreatic, lung, colorectal, and kidney cancers [5,6]. In particular, an important relationship between the presence of diabetes and a higher incidence of HCC has been confirmed [7]. This relationship occurs in association with obesity, impaired insulin sensitivity, and NAFLD, which are well-established risk factors for HCC development [8]. Independent of the presence of cirrhosis or the cause of the underlying liver disease, patients with diabetes have a 2- to 3-fold higher risk of developing HCC than individuals without diabetes [9-17]. A longer duration of diabetes may also be associated with an incremental increase in the risk of HCC [18-20], and diabetes is an independent risk factor associated with reduced overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with HCC [14,21,22]. In addition, the proportion of diabetes among patients with HCC of nonviral etiology has continued to increase considerably during the last two decades [23]. Given the rapid increase in the global incidence of HCC and diabetes, hepatologists and diabetologists must recognize the strong link between the two diseases and appropriately manage diabetes to prevent the development of liver diseases and reduce the risk of HCC.

This review article summarizes the current knowledge on the impact of diabetes on the development and progression of HCC from an epidemiologic and pathophysiologic perspective. In addition, the relationship between diabetes medications and the risk of HCC development is also discussed.

IMPACT OF DIABETES ON LIVER DISEASE PROGRESSION

There is a known close relationship between chronic liver disease and diabetes. In a recent meta-analysis involving 58 studies with 9,705 patients with cirrhosis, the overall prevalence of diabetes was 31%, with the highest prevalence in patients with NAFLD (56%), followed by patients with cryptogenic liver disease (51%), HCV infection (32%), and alcoholic liver disease (27%) [24]. Given that the liver plays a pivotal role in energy homeostasis and glucose metabolism, the close link between liver disease and diabetes is convincing.

The most common chronic liver disease observed in patients with diabetes is NAFLD [25]. As a metabolic syndrome component, T2DM can promote NAFLD. According to a recent meta-analysis involving 80 studies from 20 countries, conducted by Younossi et al. [26], the global prevalence of NAFLD and NASH among patients with T2DM was 55.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 47.3–63.7%) and 37.3% (95% CI, 24.7–50.0%), respectively. Given that the overall global prevalence of NAFLD was reported to be approximately 25% [27], diabetes is clearly associated with the incidence and progression of NAFLD. The presence of insulin resistance and diabetes is considered a risk factor for more severe liver disease in NAFLD, even in patients with normal serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) [28]. Meanwhile, NAFLD itself is associated with a 2- to 5-fold increased risk of diabetes development after correcting for various lifestyle and metabolic confounders [29].

Diabetes is a risk factor for the development and progression of liver fibrosis, and a strong relationship exists between insulin resistance and liver fibrosis progression [30]. Several large cohort studies have shown that diabetes is associated with a 2- to 2.5-fold increased risk of cirrhosis, mainly due to NAFLD, independent of other metabolic syndrome components [19,31,32 ].In contrast, glucose metabolism is altered in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Once cirrhosis is established, hyperglycemia may develop in up to 20% of patients within 5 years [33]. Furthermore, up to 80% of patients with cirrhosis may have insulin resistance, and between 20% and 60% will develop diabetes [34]. In patients with cirrhosis, hepatic insulin uptake and clearance are reduced owing to decreased liver cell mass and portosystemic venous collaterals, leading to impaired glucose tolerance and hyperinsulinemia [25]. In summary, diabetes and chronic liver disease, particularly NAFLD, can affect each other synergistically, causing the other condition to worsen.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC STUDIES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF HCC IN PATIENTS WITH DIABETES

Diabetes and cancer risk

The global prevalence of T2DM in 2019 was estimated to be approximately 9.3%, and the incidence is expected to continue to increase [35]. In parallel, the total number of deaths attributable to cancer is estimated to increase over time [1]. As there is strong evidence of a gradual increase in cancer risk and mortality with increasing incidence of diabetes [36], diabetes is considered a risk factor for the development of various cancers. In an umbrella review of the evidence across metaanalyses of observational studies on the association of diabetes with the risk of cancer development, the relative risk (RR) of HCC was 2.31 (95% CI, 1.87–2.84), the highest of the 20 cancer types [37]. Prediabetes, including impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance, is also associated with an increased risk of cancer. A meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies with 891,426 participants revealed that prediabetes was associated with an increased overall cancer risk (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.06–1.23), with a particularly high risk of HCC (RR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.45–2.79) [38]. These findings suggest that diabetes, and even prediabetic hyperinsulinemia or hyperglycemia, may be strongly associated with the development of HCC.

Diabetes and HCC risk

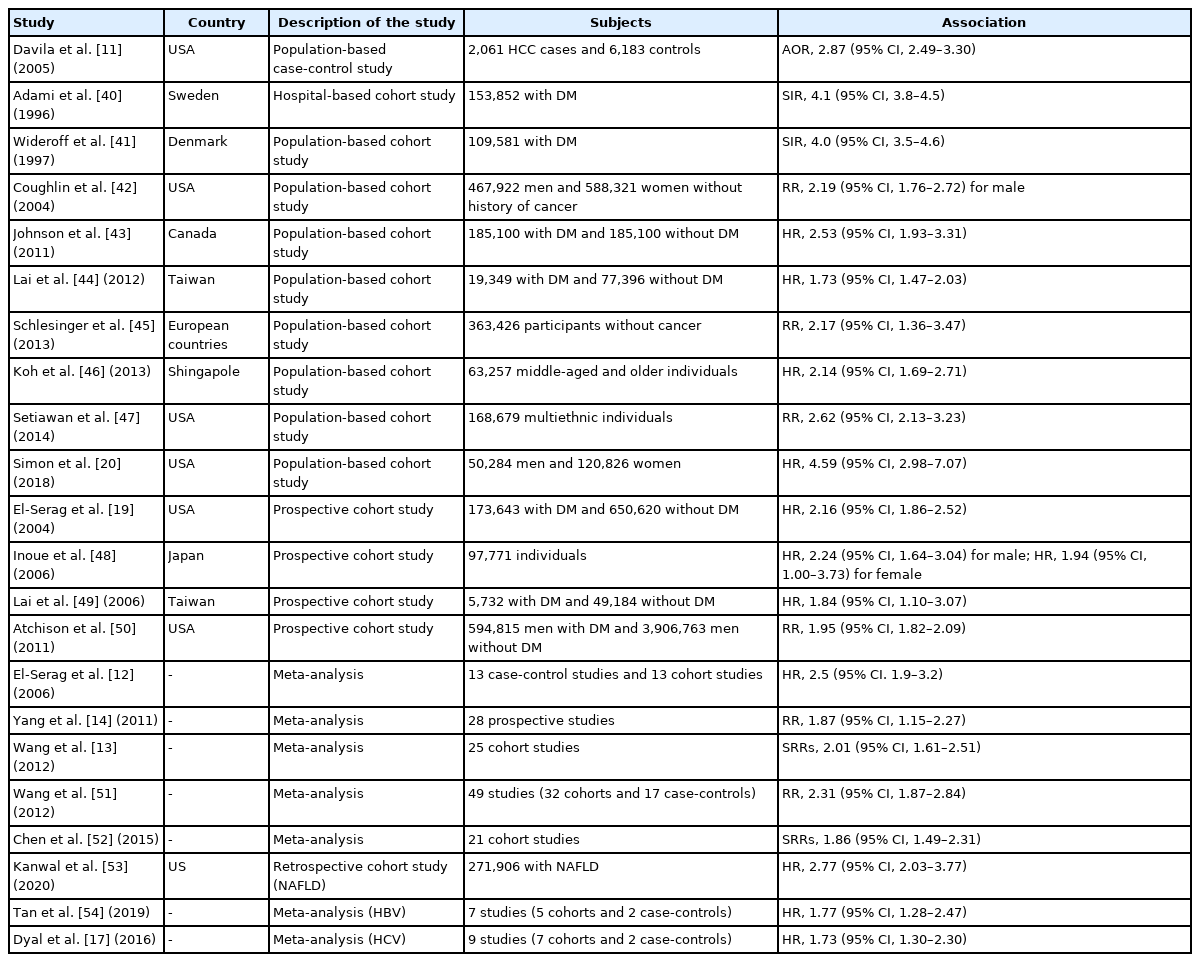

The link between diabetes and HCC was first reported approximately 40 years ago. Lawson et al. [39] observed a 4-fold excess of patients with diabetes among patients with HCC, in a case-control study involving 105 patients with HCC and equal numbers of age- and sex-matched controls. Subsequently, to date, various case-control, prospective cohort, and meta-analysis studies have shown a positive association between diabetes and an increased risk of HCC [11-14,17,19,20,40-54]. The principal observational and meta-analysis studies examining the association between diabetes and the risk of HCC are listed in Table 1. For example, El-Serag et al. [12] demonstrated that diabetes was significantly associated with the risk of incident HCC (hazard ratio [HR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9–3.2) in a meta-analysis of 13 cohort studies. The results were relatively consistent in different populations, different geographic locations, and a variety of control groups, and the association between HCC and diabetes was independent of alcohol use or viral hepatitis. In a meta-analysis of 25 cohort studies, Wang et al. [13] showed that diabetes was associated with an increased incidence of HCC (summary RR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.61–2.51) compared with the absence of diabetes, and the association was independent of geographic location, alcohol consumption, history of cirrhosis, and HBV or HCV infection. In another meta-analysis involving 17 case-control studies and 32 cohort studies, Wang et al. [51] confirmed that the combined risk estimate of all studies showed a statistically significant increased risk of HCC among individuals with diabetes (RR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87–2.84), independent of several confounding factors and metabolic variables. Furthermore, Chen et al. [52] conducted a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies and identified a total of 2,528 HCC cases in 35,202 participants. The summary RR of HCC with diabetes was 1.86 (95% CI, 1.49–2.31) in patients with chronic liver disease and 1.93 (95% CI, 1.35–2.76) in patients with cirrhosis, and subgroup analyses indicated that the positive associations were independent of geographic location, follow-up duration, and confounding factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index. In a recent large population-based cohort study including 50,284 men and 120,826 women enrolled in 1986 and followed up through 2012, Simon et al. [20] documented that diabetes was associated with an increased risk of HCC (HR, 4.59; 95% CI, 2.98–7.07), as was an increasing diabetes duration. Compared with individuals without diabetes, the multivariable HR for HCC was 2.96 (95% CI, 1.57–5.60) in those with a diabetes duration of <2 years, 6.08 (95% CI, 2.96–12.50) in those with a diabetes duration of <10 years, and 7.52 (95% CI, 3.88–14.58) in those with a diabetes duration of ≥10 years. These vast epidemiologic findings strongly suggest that diabetes has a considerable impact on the risk of HCC development, independent of various confounding factors.

Principal observational studies and meta-analysis on the association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma

Diabetes has a significant impact on hepatocarcinogenesis, particularly in patients with NAFLD. In a recent retrospective cohort study in patients with NAFLD diagnosed at 130 facilities of the Veterans Administration, Kanwal et al. [53] reported that 253 of the 271,906 patients developed HCC during a mean follow-up period of 9 years, and diabetes conferred the highest risk of progression to HCC among the metabolic factors (HR, 2.77; 95% CI, 2.03–3.77). On the other hand, diabetes also plays an important role in HCC associated with viral hepatitis. In a meta-analysis of five cohort studies and two case–control studies in patients with HBV, Tan et al. [54] demonstrated that the diabetes cohort had a higher incidence of HCC (pooled HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.28–2.47) than individuals without diabetes. In a meta-analysis of nine studies (seven cohort studies and two case-control studies) in patients with HCV, Dyal et al. [55] found that diabetes was closely associated with an increased risk of HCC (HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.30–2.30), independent of age, sex, obesity, hypertension, smoking, alcohol intake, serum liver enzyme levels, albumin, lipids, platelet count, and presence of cirrhosis or hepatic steatosis. Furthermore, Arase et al. [56] documented that diabetes caused a 1.73-fold increase in the HCC risk even after the termination of interferon therapy, in a retrospective cohort study involving 4,302 patients with HCV treated with interferon. In addition, in a recent meta-analysis involving 30 cohort studies, Váncsa et al. [15] demonstrated that diabetes was a significant risk factor for HCC in patients with HCV treated with direct-acting antivirals (adjusted HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.06–1.62). These findings indicate that diabetes is an independent risk factor for viral hepatitis-related HCC, even after viral elimination.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC MECHANISMS LINKING DIABETES WITH HCC RISK

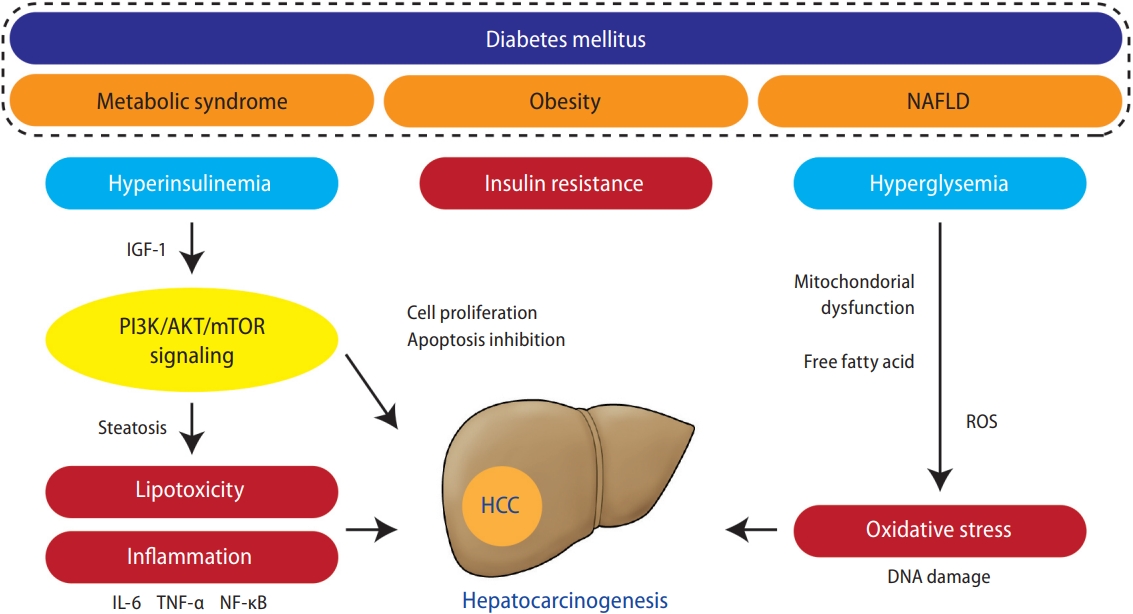

Although the detailed mechanisms of carcinogenesis in patients with diabetes remain unclear, insulin resistance-related hyperinsulinemia and DNA damage due to increased oxidative stress are assumed to be the main causes [57]. Persistent hyperinsulinemia increases the production of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding proteins, which, in turn, increase the bioavailability of IGF-1 produced by the liver. Elevated blood insulin and IGF-1 levels activate phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling, a key pathway involved in fatty liver-related carcinogenesis [58,59], which promotes hepatic cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis [60]. Furthermore, hyperglycemia increases oxidative stress production through excess glucose oxidation in mitochondria. Many patients with diabetes have metabolic factors (e.g., obesity or dyslipidemia) and develop fatty liver, in which fatty acid oxidation facilitates the generation of reactive oxygen species and increases oxidative stress production. Oxidative stress is a known cause of vascular damage in diabetes and also induces genetic mutations through oxidative DNA damage, leading to carcinogenesis [57]. Furthermore, liver fat accumulation induces chronic inflammation and increases the production of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and nuclear factor-κB, which may be involved in hepatocarcinogenesis [61]. In addition, alterations in the gut microbiota in patients with obesity and diabetes have also been implicated in NASH development and hepatocarcinogenesis [62]. Thus, a complex combination of direct and indirect mechanisms is postulated to promote hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with diabetes. The putative pathophysiologic mechanisms that may link diabetes and HCC are schematically summarized in Figure 1.

Putative key pathogenic factors that may link diabetes to HCC development. Metabolic syndrome, obesity, and NAFLD are strongly associated with diabetes. These factors induce insulin resistance-related hyperinsulinemia, leading to increased IGF-1, which promotes hepatocyte proliferation and inhibits apoptosis via activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, key pathway involved in diabetes and obesity-related hepatocarcinogenesis. Activation of PI3K signaling promotes lipogenesis, which acts on hepatocarcinogenesis directly via lipotoxicity and indirectly via the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and NF-κB. Hyperglycemia and liver fat accumulation induce mitochondria dysfunction and free fatty acid release, which promotes ROS generation and leads to oxidative stress production. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3-kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome may accelerate the progression of liver disease in patients with viral hepatitis as well as NAFLD. Diabetes and hepatitis virus infection synergistically induce the development of HCC. HCV infection itself is known to be associated with insulin resistance, which contributes to the progression of underlying liver fibrosis and the development of HCC by accelerating necroinflammation and oxidative stress in the liver [27]. Mechanistically, the core protein of the virus promotes insulin resistance by inducing the degradation of insulin receptor substrate-1 [63]. In addition, HCV proteins directly associate with mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, promoting oxidative stress [64]. On the other hand, the link between HBV and metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance remains inconclusive; HBV infection itself appears to protect against steatosis, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance [65].

INFLUENCE OF DIABETES ON HCC PROGNOSIS

Impact of HCC as a cause of death in patients with diabetes

Diabetes is an important risk factor for HCC development, whereas HCC is an important cause of death in patients with diabetes. In an analysis of individual-participant data on 123,205 deaths among 820,900 people in 97 prospective studies, the risk of HCC mortality was 2.16 times higher in patients with diabetes (95% CI, 1.62–2.88) than in those without diabetes, and the mortality risk from HCC of patients with diabetes was higher than that from all other cancers [66]. In addition, Nakamura et al. [67] investigated the principal causes of death among 45,708 patients with diabetes who died in 241 hospitals throughout Japan during 2001–2010 and found that the most frequent cause of death was malignant neoplasms (38.3%), with liver cancer (6.0%) being the second leading cause of cancer death after lung cancer (7.0%). Therefore, HCC should be recognized as both an important cause of death and an important comorbidity that cannot be overlooked in patients with diabetes.

Impact of diabetes on the prognosis of patients with HCC

Various studies have been published on the impact of diabetes on the prognosis of patients with HCC, most of which state that diabetes itself worsens the prognosis of HCC. In a nationwide prospective study including 512,869 adults from 10 regions in China, Bragg et al. [68] documented that the presence of diabetes was associated with increased mortality from liver cancer (RR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.28–1.86). In a meta-analysis of six studies reporting the risk of HCC-specific mortality, Yang et al. [14] indicated that preexisting diabetes was significantly associated with HCC-specific mortality (RR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.39–2.55) and even all-cause death (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.13–1.48), compared with the absence of diabetes. In another meta-analysis, diabetes was positively associated with HCC mortality (summary RR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.30–1.87) [13]. In addition, a meta-analysis of seven cohort studies found a statistically significant increased risk of HCC mortality (RR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.66–3.55) in individuals with diabetes [51]. In another meta-analysis involving 20 studies with a total of 9,727 patients with HCC, Wang et al. [21] demonstrated that diabetes was associated with poor overall survival (adjusted HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.27–1.91). They also revealed that diabetes was associated with poor overall survival even in patients with HCC who have undergone curative therapy, including hepatic resection or nonsurgical treatment such as radiofrequency ablation. In addition, Liu et al. [69] demonstrated that diabetes was an independent risk factor for time to progression (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.04–1.60) and cancer-specific mortality (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02–1.52) in 1,052 patients with intermediate-stage HCC who underwent transarterial chemoembolization.

However, some reports claim that the impact of diabetes on the prognosis of HCC varies depending on the clinical setting. In a meta-analysis involving 10 studies, Wang et al. [22] investigated the prognostic role of diabetes with HCC after curative treatments and demonstrated that the coexistence of diabetes impaired overall survival in patients with HCC with a tumor diameter of ≤5 cm (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.25–2.12), but not in those with a tumor diameter of >5 cm (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.39–1.15). Ho et al. [70] analyzed the prospective dataset of 3,573 patients with HCC and revealed that diabetes was not an independent prognostic predictor in all patients but was associated with decreased survival in patients within the Milan criteria (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.155–1.601) and in those with a performance status of 0 (HR, 1.213; 95% CI, 1.055–1.394).

These data suggest that diabetes worsens long-term prognosis, at least in patients with early and treatable HCC, probably owing to decreased residual liver function due to diabetes after curative treatment. Presumably, tumor factors may be more prognostic in advanced liver cancer. As non-viral HCC tends to be diagnosed at an advanced stage [71], the poor prognosis of DM-related HCC may be partly due to the lower chance of undergoing curative therapy. With recent advances in pharmacotherapy for advanced liver cancer [72], future investigations are needed to determine how diabetes affects patients with HCC who are receiving systemic treatment.

HCC SURVEILLANCE IN PATIENTS WITH DIABETES

The current regional guidelines recommend HCC surveillance only in patients with cirrhosis [73-75]. However, up to 50% of cases of NAFLD-driven HCC, which is closely associated with metabolic syndrome including diabetes, occur in patients without cirrhosis, possibly owing to its unique nature of arising from lipotoxicity-mediated chronic inflammation [4]. Some reports suggest that an annual incidence of 1.5–2.0% would guarantee the cost-effectiveness of HCC surveillance. As mentioned above, diabetes may increase the risk of HCC by approximately 2- to 3-fold; however, this is much lower than the 24-fold increased risk caused by HBV or HCV [74]. In addition, the annual incidence of HCC in patients with diabetes is estimated to be <0.1% [19], which is far below the threshold for efficient surveillance. Therefore, establishing strategies for efficient HCC surveillance in patients with diabetes has been challenging. As nonviral HCC tends to be diagnosed at an advanced stage [76] and diabetes is a factor associated with HCC detection over the Milan criteria [77], there is an urgent need for a method for detecting HCC while the disease is in a treatable state in patients with diabetes.

To date, several HCC risk prediction models have been reported. Si et al. [78] established the Korean DM-HCC risk score using data from 3,544 patients with diabetes without viral hepatitis or alcoholic liver disease. In their study, three parameters (age >65 years, low triglyceride levels, and high gamma-glutamyl transferase levels) were independently associated with an increased risk of HCC, and the weighted sum of the scores from these three parameters predicted the 10-year incidence of HCC with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.86. Li et al. [79] developed an HCC risk scoring system considering age, sex, smoking, hemoglobin A1c level, ALT level, presence of cirrhosis or viral hepatitis, antidiabetic or antihyperlipidemic medications, and total/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, using the Taiwan National Diabetes Care Management Program database including 31,723 Chinese patients with T2DM. The AUROC for the 3-, 5-, and 10-year HCC risk was 0.81, 0.80, and 0.77, respectively. These two models were based on the Cox proportional hazard model. Meanwhile, Rau et al. [80] developed an artificial neural network model for predicting HCC occurrence within 6 years of diabetes diagnosis by considering age, sex, hyperlipidemia, and chronic liver diseases, with an AUROC of 0.873. They analyzed 515 patients with diabetes who developed HCC after the diabetes diagnosis and compared them with matched 1,545 controls from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan.

Because liver fibrosis is the most important predictor of HCC development in patients with chronic liver disease, noninvasive fibrosis markers are a potential tool for risk stratification of HCC. Grecian et al. [81] tested the ability of individual fibrosis scores, including the enhanced liver fibrosis test, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index, AST-to-ALT ratio, NAFLD fibrosis score, and fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, to predict 11-year incident cirrhosis/HCC in a community cohort of 1,066 people with T2DM aged 60–75 years. All scores were significantly associated with incident liver-related events; however, they showed poor ability as a risk stratification tool, with low positive predictive values (5–46%) and high false-negative and false-positive rates (up to 60% and 77%, respectively). Recently, we investigated the best criteria for identifying candidates for HCC surveillance among patients with diabetes [82]. The study included 239 patients with T2DM and nonviral HCC with >5 years of follow-up at diabetes clinics in 81 hospitals in Japan before the HCC diagnosis and 3,277 patients with T2DM without HCC from a prospective cohort study as controls. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that the FIB-4 index was an outstanding predictor of HCC development, with an AUROC of 0.811 for predicting the 5-year HCC incidence. Furthermore, an FIB-4 cutoff value of 3.61 helped identify high-risk patients, with a corresponding annual HCC incidence rate of 1.1%. These findings suggest the importance of setting appropriate cutoff values to identify high-risk cases and the utility of the simple calculation of the FIB-4 index as the first step toward HCC surveillance in patients with diabetes. A prospective study is warranted to validate the efficacy of an FIB-4-based surveillance strategy.

MEDICATIONS FOR DIABETES MELLITUS AND HCC RISK

As previously described, diabetes has been epidemiologically proven to increase the risk of HCC development; however, whether appropriate glycemic control can prevent HCC development is controversial. Recently, Luo et al. [83] found that a higher dietary diabetes risk reduction score, reflecting better adherence to a dietary therapy for T2DM prevention, was independently associated with a significantly lower risk of HCC among 137,608 USA participants after adjusting for major known risk factors for HCC, indicating that diabetes prevention may lead to a reduced risk of HCC development. Similarly, increasing evidence has suggested the potential hepatoprotective effects of some antidiabetic drugs [84,85].

Metformin is a biguanide compound that improves insulin resistance by targeting the enzyme adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, which induces the muscle uptake of glucose from the blood. In 2005, it was first reported that the use of metformin in patients with T2DM may reduce their risk of cancer [86]. Since then, numerous studies have been conducted on the preventive effect of metformin on the development of various cancers, including HCC [87-95]. Singh et al. [90] conducted a meta-analysis involving 10 studies with 22,650 cases of HCC in 334,307 patients with T2DM and showed an overall 50% reduced risk of incident HCC among metformin-treated patients (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.50; 95% CI, 0.34–0.73). Importantly, the protective effect of metformin remained significant after adjusting for the effect of other antidiabetic medications. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis by Li et al. [92] showed that metformin use was significantly associated with a decreased risk of HCC in patients with T2DM (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.51–0.68) and even with a decreased all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes and HCC (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.66–0.83). In another meta-analysis, Zhou et al. [95] also documented that metformin significantly prolonged the survival of patients with HCC and T2DM even after the curative treatment of HCC. Considering these results, metformin use may reduce the risk of HCC development by approximately 50%. However, in these studies, metformin was not administered for the prevention of HCC but for the treatment of diabetes, leading to various biases. Home et al. [87] and Ma et al. [91] reported that two randomized controlled trials in their meta-analysis did not show a protective effect of metformin against HCC development. Singh et al. [90] also conducted a post hoc analysis of randomized controlled trials, and their results did not reveal any significant association between antidiabetic medication use and the risk of HCC. Thus, further validation based on evidence from randomized clinical trials is warranted.

Insulin is a potent mitogen associated with the upregulation of various growth factors that stimulate several signaling pathways related to cell proliferation and apoptosis inhibition [84]. Epidemiologic evidence indicates that the insulin secretion rate influences cancer risk or prognosis, and patients with diabetes treated with insulin have a higher risk of HCC [60]. Singh et al. [90] found in their meta-analysis that insulin use was associated with an increased risk of HCC (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.46–4.65). Schlesinger et al. [45] conducted a prospective analysis involving 363,426 patients with diabetes and demonstrated that treatment with insulin conferred the highest risk of HCC (RR, 5.25, 95% CI, 2.93–9.44), whereas no association was observed in participants without insulin treatment. Likewise, in a large population-based study from Italy conducted by Bosetti et al. [96], an increased risk of HCC was found with insulin use (OR, 3.73; 95% CI, 2.52–5.51), with a higher risk associated with a longer treatment duration. Although further validation is needed to clarify the true relationship between insulin use and hepatocarcinogenesis, epidemiologic and biological evidence suggests that insulin may have some hepatocarcinogenic effect.

The evidence for other classes of antidiabetic medications is limited and often inconsistent. Thiazolidinediones induce insulin sensitization and enhance glucose metabolism by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. In a randomized controlled trial, pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione, has been shown to improve the pathogenesis of NASH, a common complication of diabetes [97]. However, according to several recent meta-analyses, the potential impact of thiazolidinediones on the development of HCC remains controversial [90,98]. Similar to insulin, sulfonylureas (oral insulin secretagogues) are associated with an increased risk of cancer, including HCC. Although sulfonylureas are known to potentially increase the risk of HCC, different drug generations have shown inconsistent results [96,99,100]. In a large cohort study including 108,920 Taiwanese patients with newly diagnosed T2DM, Chang et al. [101] observed a significantly increased risk of HCC in users of first- and second-generation sulfonylureas (adjusted OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.19–1.66), but no increased risk of HCC in users of the third-generation drug glimepiride. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors work by increasing the circulating levels of incretins, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, leading to the enhancement of insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon secretion. Although experimental data indicate that DPP-4 inhibitors may reduce the risk of HCC development [102], clinical evidence on the relationship between DPP-4 inhibitors and HCC development remains scarce. GLP-1 receptor agonists such as liraglutide and semaglutide have been reported to reduce body weight and improve hepatic histology in NASH [103,104]. However, no clinical evidence exists on whether GLP-1 receptor agonists can prevent the occurrence of HCC. A new class of oral hypoglycemic agents, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, can attenuate glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule, leading to plasma glucose reduction. SGLT2 inhibitors have been reported to reduce hepatic fat content in patients with NAFLD [105]; however, there are no clinical data on whether they have a protective effect against hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with diabetes.

CONCLUSIONS

Diabetes mellitus, a disease characterized by hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance, has attracted large attention for its systemic complications. Although liver diseases, including NAFLD, NASH, cirrhosis, and HCC, are important complications of diabetes, they are often overlooked. To date, extensive epidemiologic and preclinical evidence has supported a robust association between diabetes and liver diseases, including HCC. In addition, a bidirectional relationship exists in that advanced liver disease may induce the onset of diabetes and diabetes is a recognized risk factor for the development and progression of liver disease and HCC. The association between these two diseases is complex, and further research is needed to clarify the causal relationship. Mechanistically, diabetes and liver cancer share common pathologies, including insulin resistance-related hyperinsulinemia, DNA damage due to increased oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation or lipotoxicity induced by liver fat accumulation.

In recent decades, diabetes and HCC have both become socioeconomic problems with high incidence rates worldwide, in the context of a growing population of individuals with obesity and an increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome. However, there is no established method for appropriate HCC surveillance in patients with diabetes, and HCC is often detected at an incurable stage. Although some antidiabetic drugs are expected to prevent HCC development, further research on the optimal use of antidiabetic drugs aimed at hepatoprotection is essential. In summary, diabetologists and hepatologists need to work together to study liver diseases in patients with diabetes, and further evidence on the prevention and early detection of HCC occurring in association with diabetes is desired.

Notes

Authors’ contributions

TN and RT contributed to the literature review and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 21K15989 (TN) and 20K08352 (RT), Program on Hepatitis from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP21fk0210090 (RT) and JP21fk0210066 (RT), and the Health, Labour, and Welfare Policy Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Laboure, and Welfare of Japan H30-Kansei-Shitei-003 (RT).

Abbreviations

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

AST

aspartate aminotransferase

AUROC

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

CI

confidence interval

DDP-4

dipeptidyl peptidase-4

FIB-4

fibrosis-4

GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

HBV

hepatitis B virus

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV

hepatitis C virus

HR

hazard ratio

IGF

insulinlike growth factor

IL-6

interleukin-6

NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

OR

odds ratio

PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-kinase

RR

relative risk

SGLT2

sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

TNF

tumor necrosis factor