Crosstalk between tumor-associated macrophages and neighboring cells in hepatocellular carcinoma

Article information

Abstract

The tumor microenvironment generally shows a substantial immunosuppressive activity in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounting for the suboptimal efficacy of immune-based treatments for this difficult-to-treat cancer. The crosstalk between tumor cells and various cell types in the tumor microenvironment is strongly related to HCC progression and treatment resistance. Monocytes are recruited to the HCC tumor microenvironment by various factors and become tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) with distinct phenotypes. TAMs often contribute to weakened tumor-specific immune responses and a more aggressive phenotype of malignancy. Recent single-cell RNA-sequencing data have demonstrated the central roles of specific TAMs in tumorigenesis and treatment resistance by their interactions with various cell populations in the HCC tumor microenvironment. This review focuses on the roles of TAMs and the crosstalk between TAMs and neighboring cell types in the HCC tumor microenvironment.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for nearly 800,000 deaths worldwide [1]. In 2018, the estimated incidence of HCC in South Korea was 21.2 per 100,000 person-years, representing the fifth and sixth most common cancer in men and women, respectively [2]. HCC is associated with inflammation and stems from chronic hepatic injury [1]. Worldwide, the incidence and mortality of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-related HCC are increasing, reflecting an increasing prevalence of obesity [3]. Although early-stage HCC can be treated with surgical resection and locoregional treatments, such as percutaneous ablation, the disease is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage. HCC is managed by palliative systemic therapy in such cases, which in the past 10 years have relied primarily on the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib [4]. Recently, several TKIs for the first- and second-line management for advanced HCC, including lenvatinib, cabozantinib, and regorafenib, have been approved and are now clinically used [1].

Immune-based HCC treatments have various clinical advantages beyond their high response rates. One benefit is related to the quality of life. Patient-reported outcome data have demonstrated improved quality of life with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab treatment compared to that with sorafenib [5]. Nivolumab was recently approved as a second-line therapy, and atezolizumab plus bevacizumab were shown to be superior to sorafenib as primary treatment for advanced HCC [6]. However, the first approved antiprogrammed death (PD)-1 antibody, nivolumab, has an objective response rate (ORR) of <20% in HCC [7,8]. The Checkmate-040 study of unresectable HCC revealed that programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in >1% of tumor cells is associated with a 28% ORR for nivolumab, compared with a 16% ORR with PD-L1 expression in <1% of tumor cells. These findings need to be validated because the expression of PD-L1 in nonparenchymal cells was not considered [9,10].

The liver has a unique immunological environment comprising various immune cell types, presenting a considerable challenge for immunotherapy in HCC. The responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are critically shaped by the tumor microenvironment (TME). Especially, they are impeded by the activity of immunosuppressive cells, including regulatory T cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs), and neutrophils, which are associated with an unfavorable prognosis [11]. Also, TAMs have central immune-regulatory roles and may limit the efficacy of immune-based therapy via crosstalk with tumor and killer cells [12]. Immune subtyping using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas describes HCC as a C4 subtype associated with an M2 macrophage enrichment [7,13,14]. Single-cell RNA-sequencing analyses identified two important clusters of immune-suppressive cells in the TME of HCC [15]. One corresponds to TAMs and the other is lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 3-positive dendritic cells (DCs) [15]. Another single-cell analysis of primary and early-relapse HCC samples demonstrated that macrophages are enriched in tumors compared with their levels in adjacent nontumors [16]. Analyses of macrophage pro- and antiinflammatory scores demonstrated that infiltrated macrophages have an immunosuppressive phenotype [16]. Collectively, recent single-cell RNA-sequencing reports demonstrate that TAMs constitute a principal immunosuppressive population in the TME of HCC [15-17].

This review focuses on the origin and functional characteristics of TAMs and their crosstalk with other cell types in the TME of HCC.

IMMUNOLOGICAL HETEROGENEITY OF HCC

HCC is typically characterized by the gradual dysfunction of innate-like and adaptive immune cells and an increase in the number of immune-regulatory cells in the TME [14]. Recently, a trajectory from proliferative to exhausted CD8+ T cells was shown in HCC by an RNA velocity analysis [15]. When T cells are exhausted, the expression of several inhibitory receptors, including PD-1, lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), and T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), is upregulated and the effector function is impaired by transcriptional changes mediated by TOX [18]. The exhausted CD8+ T cell population is heterogeneous. Two identified subgroups are PD-1+ TCF1+ cells, capable of self-regeneration, and terminally exhausted PD-1+ TCF1– cells [19-21]. The response to anti-PD-1 improves when PD-1+ TCF1+ cells are dominant, but not when the terminally exhausted PD-1+ TCF1– T cells replace their precursors in the TME [19-21].

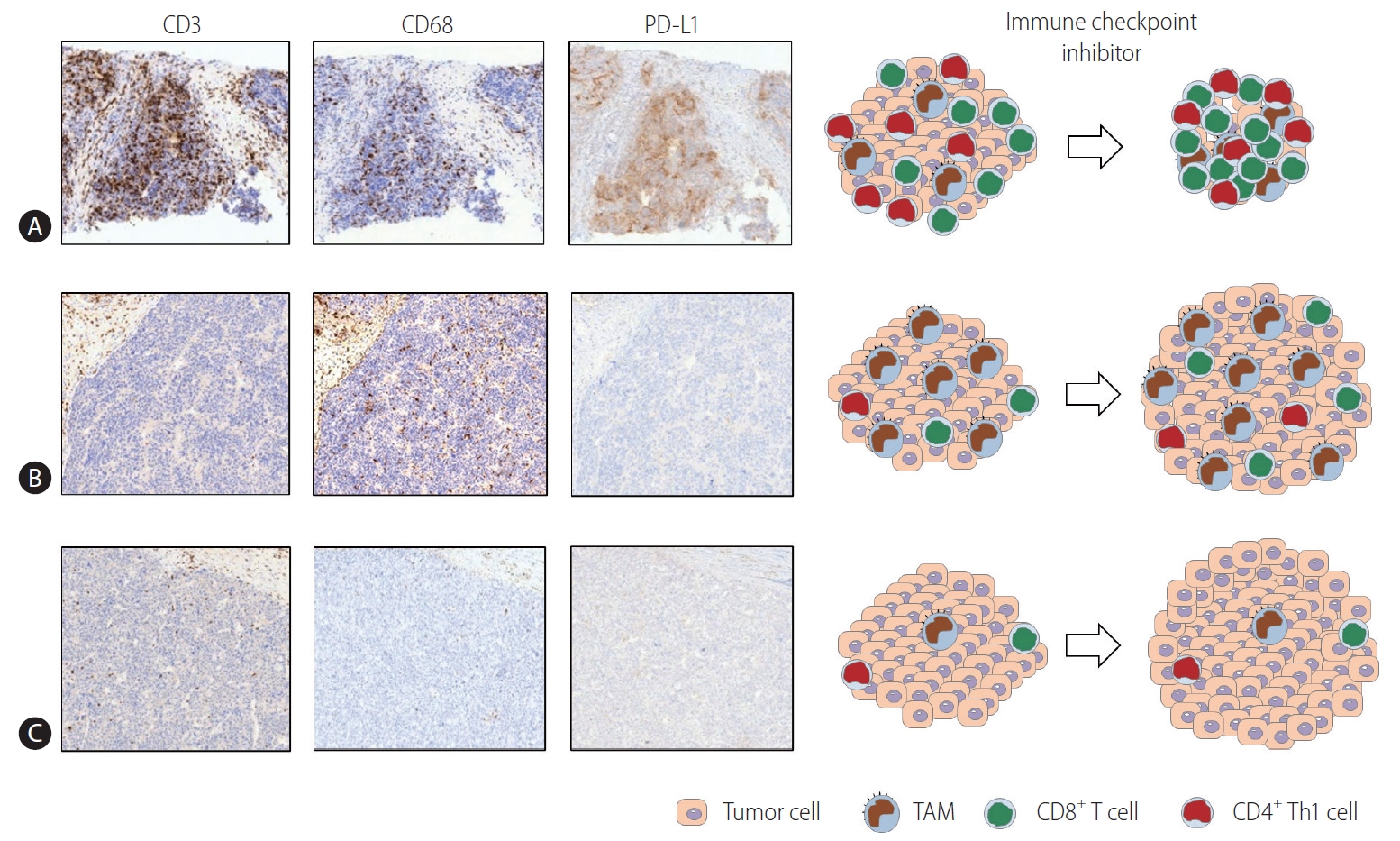

Multiplex immunohistochemistry and gene expression assays of 919 regions of 158 HCC tissues revealed that the immune microenvironment in HCC is heterogeneous and can be classified into three different subtypes: immune-high, -mid, and -low [22]. These “immune classes” are related to patient survival [22]. The immune-high class can be further divided into two TME-based subclasses. The “active immune” subclass is supplemented with T cell effectors, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and granzyme B signatures. The “exhausted immune” subclass includes signatures of exhausted T cells, immunosuppressive TAMs, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling [22]. A subsequent broader multiomics analysis characterized “immunocompetent,” “immunosuppressive,” and “immunodeficient” HCC subtypes [23]. The immunocompetent subtype exhibited a robust T cell infiltration, whereas immunosuppressive cells (including regulatory T cells and TAMs) and molecules such as PD-L1 were abundant in the immunosuppressive subtype [23]. Figure 1 schematically depicts the three HCC immune subtypes [22,23]. Representative immunohistochemistry data using CD3 (T cell marker), CD68 (macrophage marker), and PD-L1 antibodies for three immune subtypes of HCC have been acquired (unpublished data).

Three HCC immune subtypes. The three immune subtypes of HCC described in previous studies [22,23] are schematically depicted. Representative immunohistochemistry using CD3 (T cell marker), CD68 (macrophage marker), and PD-L1 antibodies for three immune subtypes of HCC is also presented (unpublished data). (A) This subtype exhibits a robust infiltration of T cells (CTLs and Th1 cells) and M1-dominant TAM infiltration. The high expression of PD-L1 in TAMs with or without in tumor cells reflects the immunogenic nature of the tumor. This phenotype may respond well to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies. (B) In this subtype, immunosuppressive cells including TAMs are abundantly infiltrated. However, there are few infiltrating T cells. TAMs may show PD-L1 expression, although the level of PD-L1 is not as high as that in cells with an immunocompetent phenotype. This phenotype may not respond well to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies, and immune-based combination treatments for this subtype may be required. (C) This subtype may be referred to as the “immunodeficient” subtype. The infiltration of T cells and TAMs is poor, which may stem from poor tumor immunogenicity. This subtype may not respond to immune-based therapy unless antigen release by the locoregional or systemic therapies results in local inflammation sufficient to cause the infiltration of immune cells. PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Based on the immunohistochemical staining of various immune markers, a myeloid-specific prognostic signature, referred to as the myeloid response score (MRS) for HCC, was developed [24]. MRS has remarkable discriminatory power in predicting survival in HCC [24]. A higher MRS implies a stronger protumoral activity in the TME of HCC, accompanied by an increased CD8+ T cell exhaustion [24]. These findings emphasize the critical contributions of myeloid cells to immune heterogeneity in HCC. A recent study using whole-genome and RNA sequencing and cytometry by time-of-flight analysis with multiple tumor sectors demonstrated a notable immune intratumoral heterogeneity in HCC [25]. Tumors with pronounced immune intratumoral heterogeneity displayed a more immunosuppressive TME associated with worse clinical outcomes [25].

Clinically, the maximal tumor diameter is the only significant pretreatment parameter for the prediction of survival outcomes after nivolumab treatment [26]. The response to nivolumab differs according to tumor size in patients with HCC, perhaps stemming from intratumoral heterogeneity in larger tumors [27]. This heterogeneity may be explained by an innate or acquired resistance of tumor cells, or by the frail immune environment, and must be overcome to maximize treatment efficacy. Immune-based combination therapies with synergistic effects may be an inevitable approach [28]. Indeed, bevacizumab plus atezolizumab, lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab, and camrelizumab plus apatinib have achieved promising ORRs in clinical trials for advanced HCC [1,28].

ORIGINS AND FUNCTIONS OF LIVER MACROPHAGES

There is considerable heterogeneity within intrahepatic macrophage pools. Two subgroups of liver macrophages are identified depending on their origin and activity. Kupffer cells (KCs) are derived from erythromyeloid progenitor cells in the fetal yolk sac. KCs are liver-resident, nonmigratory macrophages capable of self-regeneration [29]. They are found in the hepatic sinusoids and differ from circulating monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMfs) stemming from the bone marrow [30]. KCs and MoMfs have overlapping phenotypes and are challenging to differentiate in humans owing to a lack of lineage-specific markers [30]. Multiple MoMfs differentiate and exhibit a phenotype that, under specific conditions, is virtually identical to that of KCs [31,32]. Two markers have been proposed as candidates to distinguish MoMfs from KCs: C-type lectin domain family 4 member F (Clec4F) and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing 4 (Tim4) [33]. Clec4F and Tim4 are expressed in KCs but are not present in infiltrating MoMfs [33,34].

Accounting for approximately 20% of hepatic nonparenchymal cells, KCs have a key role in host defense and coordinate the inflammatory response when they detect pathogens [35]. They are involved in phagocytosis, antigen processing and presentation, and the production of proinflammatory mediators. Initially, they produce cytokines conducive to inflammation, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18 [35]. CCL2 is a representative chemokine produced by activated macrophages, monocytes, and DCs when they are stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines [36]. In the early phase of hepatic inflammation, KCs produce CCL2 to coordinate the mobilization of circulating monocytes to the liver [37]. MoMf mobilization to the liver occurs during inflammation or following the experimental depletion of KCs in a CCL2/CCR2-dependent manner [38].

KCs can also be activated by an interplay with platelets in NASH livers [39]. Hyaluronic acid on the surface of KCs and the glycoprotein 1b alpha (GPIbα) platelet receptor subunit are critical for NASH and subsequent HCC [39,40]. Resident KCs decrease and are replaced by a specific set of MoMfs over time in NASH [41]. One subset of recruited MoMfs in NASH is termed hepatic lipid-associated macrophages. These cells express osteopontin [41]. When inflammation begins in NASH livers, KCs and recruited MoMfs differentiate into proinflammatory macrophages [42]. A recent study of human NAFLD livers demonstrated that gut-derived lipopolysaccharides may increase liver damage by activating macrophages via the toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 pathway [43]. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) is predominantly expressed in a subset of intrahepatic macrophages and inhibits TLR signaling [44]. When chronic inflammation is not resolved, profibrogenic TREM2+ CD9+ scar-associated macrophages differentiate from MoMfs and expand in the fibrotic liver [45].

ORIGINS AND FUNCTIONS OF TAMs IN HCC

A recent cross-tissue, single-cell analysis of human macrophages demonstrated that every cancer type involves the infiltration of conserved TAM populations [46]. The IL4I1+ PD-L1+ IDO1+ and TREM2+ TAM subsets accumulate in various types of human cancers, including HCC. The cells display immunosuppressive phenotypes and promote the infiltration of regulatory T cells [46]. Moreover, recent single-cell RNA-sequencing data for HCC tissues demonstrated that TAM subgroups are not associated with liverresident KCs (MARCO+) or MDSCs (CD33+), suggesting that TAMs mainly originate from circulating monocytes [16]. A recent report based on imaging mass cytometry of 562 highly multiplexed HCC tissue samples demonstrated that regional immunity is determined by resident KCs with a protumor function and infiltrating macrophages with an antitumor function [47]. This suggests that the specific targeting of KCs, rather than overall myeloid cell blocking, should be a novel immunotherapy for HCC.

Monocytes can be recruited by chemokines. The CCL2-CCR2 signaling axis may be a significant target for monocyte recruitment in the TME of HCC. CCR2 antagonist treatment effectively impedes HCC tumor growth in different murine models [48]. This therapeutic approach blocks Ly-6Chigh inflammatory monocyte infiltration, resulting in a reduction in the number of TAMs in the TME of HCC [49]. In addition, the phenotype of residual TAMs reportedly shifts to the M1 phenotype by CCR2 targeting [49]. An antitumor effect of a CCL2-neutralizing antibody through a decrease in the inflammatory myeloid cell population, and the enhanced function of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells was demonstrated in a murine HCC model [50]. Several phase I/II clinical trials using a CCR2/5 inhibitor in combination with ICIs for various solid tumors are expected to provide additional insights toward improving the efficacy of ICIs [51].

Macrophages are classified into M1 or M2 according to their phenotypes [52]. Macrophage polarization is influenced by tumor stage and differs among tumors or areas within a tumor [34]. HCC tumor progression was once considered to be associated with a skew in the macrophage phenotype from M1 to M2 phenotypes [33,53,54]. However, recent single-cell analyses have revealed coexisting M1 and M2 signatures in TAMs, indicating that the TAM phenotype may not be simply defined by using the classical M1/M2 model [16]. The TME of HCC is infiltrated by PD-L1-expressing “activated” monocytes with protumoral features [55,56]. Generally, PD-L1 is expressed at a higher level in macrophages/monocytes with an activated M1 phenotype [12]. Therefore, TAMs in the TME of HCC cannot be defined as a pure M2 phenotype. Rather, they are composed of heterogeneous populations in terms of M1/M2 polarization. The expression of PD-L1 was reported to be higher in macrophages compared to that in cancer cells, providing a potential indicator for the response to immunotherapy in HCC. Additionally, PD-L1+ TAMs from the analyzed HCC samples did not exhibit a complete M2 polarization [12]. Additionally, these TAMs exhibited a high HLA-DR expression, reflecting the potential immunogenic nature of tumor cells and susceptibility to therapy designed to deplete these PD-L1-expressing TAMs [57,58].

CROSSTALK BETWEEN TAMs AND TUMOR CELLS IN HCC

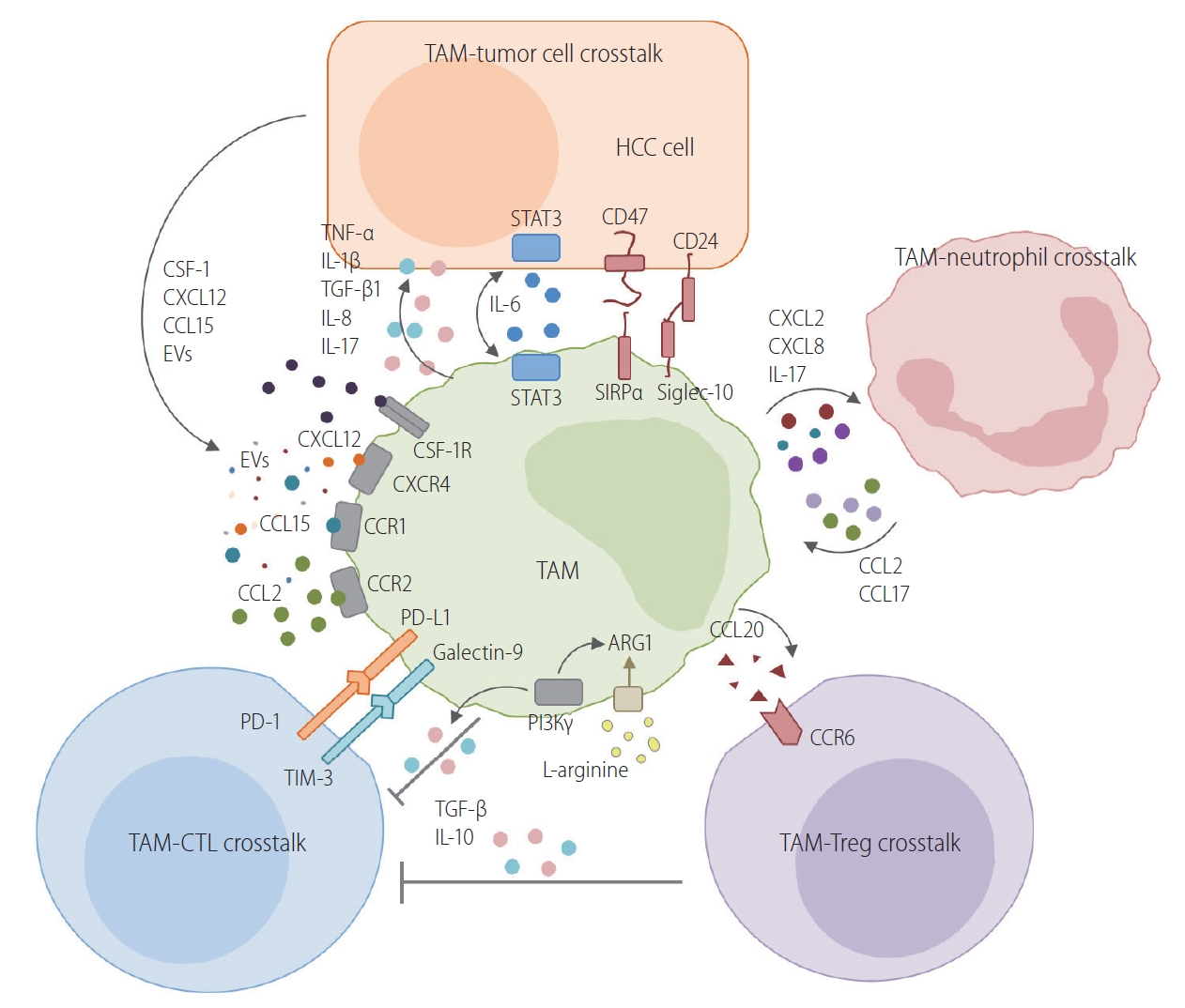

TAMs interact with tumor cells in various ways in HCC. Figure 2 schematically describes the routes of crosstalk between TAMs and neighboring cells in the TME of HCC. The following subsections describe the current evidence for a crosstalk between TAMs and tumor cells.

Crosstalk between TAMs and neighboring cells in the TME of HCC. TAMs interact with tumor cells in various ways in HCC. This figure schematically describes the crosstalk between TAMs and neighboring cells in the TME of HCC. One route is the crosstalk between TAMs and tumor cells. Various cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles are produced by tumor cells. Macrophages are recruited and differentiate into TAMs. TAMs also produce various cytokines that confer a malignant potential to tumor cells. The direct crosstalk between TAMs and HCC tumor cells is mediated by CD47/SIRPα or CD24/siglec-10 pathways. TAMs have a critical crosstalk with CTLs, resulting in the inhibition of anti-tumor activity with the involvement of the PD-1/PD-L1 or TIM-3/galectin-9 pathway. Moreover, PI3Kγ mediates the immunosuppressive activity of TAMs by enhancing arginase-1 activity and the IL-10 secretion of TAMs. L-arginine depletion by an enhanced arginase-1 activity in TAMs also causes the exhaustion of antigen-specific T cells in the TME. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are also recruited to the TME of HCC by CCL20. CCL20 is produced by TAMs and binds to CCR6 in Tregs. Neutrophils are recruited to the TME by chemokines produced by TAMs. They also recruit TAMs by secreting CCL2 and CCL17. Collectively, TAMs usually have central immunosuppressive roles in the TME of HCC, although the phenotype of these macrophages varies significantly because of the heterogeneity of HCC. TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CSF-1, colony-stimulating factor-1; EVs, extracellular vesicles; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL, interleukin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; SIRPα, signal regulatory protein alpha; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TIM-3, T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3; PI3Kγ, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma; TME, tumor microenvironment.

Direct crosstalk

Liver cancer stem cells are the cause of the aggressiveness and treatment resistance in HCC [59]. CD24 is preferentially expressed in a subset of liver cancer stem cells [60]. Generally, CD24-expressing tumors can be protected from phagocytosis because CD24 interacts with siglec-10, an inhibitory receptor expressed by TAMs [61]. Therefore, it can be inferred that CD24-expressing liver cancer stem cells can also evade macrophage phagocytosis.

Signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) is an inhibitory receptor molecule expressed on macrophages. SIRPα interacts with CD47 on tumor cells [62]. It is considered a key immune-modulatory checkpoint of macrophages [62]. SIRPα expression in macrophages is correlated with poor survival in HCC [63]. In tumor cells, the CD47-SIRPα interaction acts as a protective signal to evade macrophage surveillance and phagocytic removal [64]. Treatment with anti-CD47 antibodies promotes the phagocytosis of tumor cells via activated macrophages [65]. Anti-CD47 treatment combined with doxorubicin further enhances macrophage phagocytosis, suggesting that anti-CD47 antibody treatment could be complementary to transarterial chemoembolization in HCC [66].

Cytokines/chemokines

CD133+ liver cancer stem cells secrete IL-8 [67], which stimulates M2 polarization of TAMs to enhance the tumor’s malignant potential [68,69]. TAMs are a principal source of paracrine IL-6 [70]. IL-6 generated by TAMs stimulates tumor cells [71], resulting in the intracellular activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway to increase the proliferation of liver cancer stem cells [71]. M2 polarization is reportedly stimulated by the activation of IL-6/STAT3 signaling in macrophages [70]. Therefore, anti-IL-6 treatment may have direct and indirect antitumor effects in HCC. TNF-α derived from TAMs promotes cancer stemness in HCC by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [72]. Within a hypoxic microenvironment, the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in HCC cells could be induced by IL-1β produced by TAMs via the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α)/IL-1β/TLR4 pathway [73]. Furthermore, the EMT of tumor cells may also be triggered by IL-8 secreted from TAMs via the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/STAT3/Snail pathway [74,75]. The EMT of tumor cells is also activated by TGF-β1 produced by TAMs [76].

Tumor cell autophagy can be induced by cytokines produced by TAMs and may also confer resistance to cytotoxic stimuli [77]. Oxaliplatin cytotoxicity in SMMC-7721 and Huh-7 cell lines and HCC xenografts may be suppressed by tumor cell autophagy activated by TAMs [78]. When HCC is treated with oxaliplatin, M2-TAMs produce more IL-17, promoting autophagy in cancer cells [79]. The autophagy of macrophages themselves also has a critical impact on HCC development and progression [33]. Autophagy-deficient KCs promote inflammation and HCC development by enhancing the activity of the mitochondrial reactive oxygen species/nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)/IL-1α/β signaling axis [80]. A recent study using mice with a myeloid-specific knockdown of ATG5 demonstrated an increased hepatocarcinogenesis and altered antitumoral immune response compared to wild-type mice [81]. Collectively, these findings suggest that various cytokines produced by TAMs critically influence tumor cells and macrophages.

CCL15 is one of the most abundantly expressed chemokines in HCC cells. It recruits CCR1+ cells to the TME of HCC [82]. The recruited CCR1+ CD14+ monocytes express significantly higher levels of immune checkpoint molecules, including PD-L1 and TIM-3 [82]. The activated CCL15-CCR1 axis indicates an inflammatory microenvironment infiltrated with CCR1+ monocytes and tumor cells with high metastatic potential and may become a target for HCC therapy [82].

CSF-1/CSF-1R axis

Differentiation and functioning of macrophages can only be achieved by stimulation with colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and its receptor, CSF-1R. Tumor cells can directly recruit TAMs via the CSF-1/CSF-1R axis. In HCC tumor cells, SLC7A11, whose expression is positively associated with worse tumor differentiation, upregulates the expression of CSF-1 and PD-L1 via the alpha-ketoglutarate-HIF1α cascade [83]. SLC7A11 overexpression in tumor cells promotes TAM infiltration in the TME of HCC via the CSF-1/CSF-1R axis [83]. The CSF-1 pathway is activated by miR-148b depletion in HCC cells, which promotes TAM recruitment into the TME of HCC [84]. Another microRNA, miRNA-26a, suppresses macrophage recruitment by downregulating CSF in HCC cells [85].

The use of a competitive CSF-1R inhibitor substantially impedes tumor growth in murine xenograft models. TAMs in CSF-1R inhibitor-treated tumors are polarized toward an M1-like phenotype, as determined by gene expression profiling [86]. In mouse models of HCC, two possible consequences of blocking the CSF-1/CSF-1R signaling pathway were identified: TAM reprogramming from the M2 phenotype to the M1, and the suppression of PD-L1 expression, potentiating the response to PD-1/PD-L1 therapy [86,87].

Crosstalk by extracellular vesicles

Exosomes from TAMs may promote tumor growth and cancer stemness in HCC. A recent study showed that the exosome-mediated transfer of functional CD11b/CD18 protein from TAMs to tumor cells enhances the migratory potential of HCC cells [53]. miR125a/b in exosomes inhibited the activity of liver cancer stem cells by targeting CD90, although TAM-derived exosomes had decreased levels of miR-125a/b to increase tumor cell stemness [88]. Conversely, emerging evidence indicates that tumor cell-derived exosomes or exosomal miRNAs contribute to HCC progression by enhancing macrophage infiltration or activation. Endoplasmic reticulum stress causes tumor cells to secrete exosomal miR-23a-3p [89]. The exosomal transfer of miR-23a activates the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-AKT pathway and increases PD-L1 expression in macrophages [89]. Exosomes of tumor cells are also enriched in miR-146a-5p, which results in the M2-polarization of TAMs and may cause T cell exhaustion [90].

CROSSTALK BETWEEN TAMs AND NK CELLS IN HCC

In the TME of HCC, NK cells are less abundant and dysfunctional [59]. A major mechanism regulating NK cell function is the crosstalk between various immune cell populations, such as TAMs, in the TME of HCC [91]. TAMs indirectly inhibit NK cells via cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β [91]. Additionally, TAMs express CD48 in the TME of HCC and may directly interact with 2B4 on NK cells, resulting in NK cell dysfunction [92]. Conversely, M1 macrophages may increase the total number of activated intrahepatic NK cells in chronic liver diseases [93]. This suggests that when TAMs are repolarized to the M1 phenotype, they may stimulate NK cells to kill tumor cells.

CROSSTALK BETWEEN TAMs AND T CELLS IN HCC

TAMs can regulate the tumor cell killing ability of T and NK cells. This TAM-mediated suppression, rather than tumor cell-mediated suppression, may be the principal mechanism underlying tumor-specific T cell dysfunction in the TME of HCC. A decade ago, two studies independently demonstrated that macrophages are the principal nonparenchymal cells in the TME that express PD-L1 in HCC [94,95]. These findings were confirmed in several subsequent studies. A recent spatial analysis revealed a positive correlation between the number of infiltrating PD-1highTIM3+ CD8+ T cells and the number of PD-L1+ TAMs and a lack of correlation with the number of PD-L1+ tumor cells [96]. Likewise, our group obtained similar results showing that PD-L1+ TAMs, but not PD-L1+ tumor cells, are located near infiltrating CD8+ T cell subsets [96]. A recent study confirmed that PD-L1 on TAMs suppresses tumor-specific T cell responses in HCC [97]. Using a myeloid-specific pdl1-knockout mouse model, the authors demonstrated that PD-L1 on TAMs directly suppresses intratumoral CD8+ T cells [97]. They also found that tumor-derived Sonic hedgehog causes the upregulation of PD-L1 in TAMs [97].

Arginine metabolism is critically related to TAM polarization [98]. The production of nitric oxide (NO) from arginine in M1 macrophages causes cytolysis of tumor cells, although M2 macrophages have increased enzymatic activities of arginase with a reduction in arginine levels and NO production [98]. Arginine is a critical amino acid involved in antitumor immunity involving the activation of T cells via T cell receptor upregulation [99]. Arginase produced by TAMs and MDSCs depletes extracellular arginine and suppresses T cell activation [100]. Supplementation with arginine normalizes T cell metabolism from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation and promotes survival and antitumor activity, suggesting that arginine deficiency by M2 macrophages is a target for immunotherapy in HCC [101].

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma (PI3Kγ) stimulates the activation of the “immunosuppressive program” in TAMs [102]. Macrophage PI3Kγ suppresses T cell activation, while the lack of its activity in TAMs reduces the production of immunosuppressive molecules, including IL-10 and arginase, and enhances antitumor T cell responses [102]. Another study demonstrated the potential value of targeting myeloid-intrinsic PI3Kγ to overcome ICI resistance [103]. These critical roles of PI3Kγ in TAMs need to be confirmed in HCC.

In chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, rapid viral eradication by direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) changes the phenotype of infected hepatocytes and intrahepatic monocytes/macrophages while contributing to HCC [20,104,105]. The inflammatory activity of intrahepatic macrophages, which is closely associated with mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cell activity, is markedly attenuated after rapid viral clearance by DAAs [106]. MAIT cells are activated by IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18, which are usually produced by activated macrophages/monocytes [107]. Usually, DAA therapy causes an immediate reduction in IL-18 levels in chronic HCV infection, resulting in a rapid decrease in intrahepatic inflammation and MAIT cell cytotoxicity [108,109]. The decreased cytotoxicity of MAIT cells with the reduction in proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages after DAA treatment may be related to HCC recurrence after DAA-mediated HCV clearance.

CROSSTALK BETWEEN TAMs AND REGULATORY T CELLS IN HCC

Regulatory T cells are a major immunosuppressive cell population and have various effects on tumor progression [110]. A recent study in which the CIBERSORT algorithm was used to estimate the relative frequencies of 22 subsets of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in 1,090 HCC cases revealed four tumor clusters [111]. Tumors with increased regulatory T cells and decreased M1 macrophages were associated with a worse prognosis [111]. However, M2 TAMs, and not M1 macrophages, tend to promote the recruitment of regulatory T cells to the TME. The infiltration of TREM-1+ TAMs in the TME of HCC is critical for resistance to anti-PD-L1 within the hypoxic TME by the recruitment of CCR6+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via CCL20 production [112]. The recruited or induced regulatory T cells can further enhance the immunosuppressive properties of TAMs. Regulatory T cells promote the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1)-mediated metabolic processes of M2 TAMs by repressing the production of IFN-γ by CD8+ T cells [113]. Therefore, regulatory T cells indirectly sustain M2 TAM survival, forming a positive feedback pool [113].

CROSSTALK BETWEEN TAMs AND T FOLLICULAR HELPER CELLS/PLASMA CELLS IN HCC

HCC is a typical example of inflammation-associated cancer [114]. TAMs also cause cancer-related inflammation, resulting in the generation of an inflammatory helper T cell subset, such as T follicular helper cells, in the TME of HCC [115]. TLR4-induced monocyte activation is critical for the generation of IL21+ T follicular helper cells with a CXCR5– PD-1– BTLA– CD69high tissue-resident phenotype in the TME of HCC. These cells induce plasma cells, leading to the ideal conditions for M2 TAM induction and cancer progression [115].

Liver IgA+ plasma cells directly suppress cytotoxic T cell activation in vitro and in vivo, inducing their exhaustion [116]. Moreover, recent data have demonstrated that IgA complex-stimulated monocytes/macrophages also show an inflammatory phenotype and express higher PD-L1 levels in the TME of HCC [117]. These IgA+ TAMs may be a target for improving the efficacy of immune-based therapy in HCC.

CROSSTALK BETWEEN TAMs AND NEUTROPHILS IN HCC

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) might support the progression of tumors by hampering antitumor immunity [118]. Monocyte-derived CXCL2 and CXCL8 play critical roles in recruiting neutrophils into the TME of HCC [119]. A recent study demonstrated that the glycolytic switch in monocytes mediates the upregulation of CXCL2 and CXCL8 via the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3-NF-κB pathway [119]. Moreover, the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17 contributes to TAN recruitment to the TME [118]. Neutrophils also have critical functions in the recruitment of macrophages and regulatory T cells to the TME of HCC via the production of cytokines or chemokines [120]. Besides, a positive correlation has been observed between the extent of TAN infiltration and angiogenesis at the tumor-invading margin in patients with HCC [121]. CCL2 and CCL17 are the chemokines robustly produced by TANs and peripheral blood neutrophils, which strongly recruit macrophages into the TME of HCC [120]. Therefore, the infiltration of TANs is a poor prognostic factor, because they further recruit TAMs and block tumor-specific immunity in HCC.

MODULATION OF THE TAM POPULATION BY CURRENT HCC THERAPIES

Although many innovative approaches to modulate TAMs are now being developed, no specific methods targeting TAMs in HCC are currently being clinically implemented. The following sections focus on the effects of current HCC therapies on TAMs in the TME. Figure 3 schematically describes various HCC treatments and their immune-modulating effects.

Modulation of the TAM population in the TME of HCC by current standard therapies. This figure schematically describes the various HCC treatments and their effects on TAMs. Transarterial therapy, such as transarterial chemoembolization or transarterial radioembolization and radiation therapy, may activate TAMs in the TME of HCC to exhibit an M1-like phenotype and enhance their antigen presentation. In response to TAM activation, the number and cytolytic function of infiltrated CTLs may be increased by these therapeutic modalities. One of the multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitors for HCC, lenvatinib, is known to have robust immune-modulating effects for HCC. Lenvatinib decreases the number of infiltrated TAMs and activates CTLs in the TME. Conversely, intratumoral hypoxia caused by sorafenib, another multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for more than a decade, may increase the number of TAMs in the TME of HCC, resulting in decreased CTL activity. In immunogenic HCC, PD-L1 is preferentially expressed in TAMs, rather than in tumor cells. ICI treatment in HCC activates these PD-L1+ TAMs, resulting in enhanced CTL activity. TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TME, tumor microenvironment; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Locoregional treatments/radiotherapy (RT)

There is strong evidence that the combinatorial approach of locoregional therapies with ICIs enhances the immune-modulatory effect of locoregional therapies in HCC [122]. Transcriptomic analysis and the deep immunophenotyping of tissues from patients undergoing Y90-radioembolization demonstrated strong immune activation in the TME and peripheral blood of patients with prolonged responses [123]. Interestingly, a significantly higher proportion of peripheral CD14+ HLADR+ monocytes was observed 3 months after therapy in patients with sustained responses, suggesting that the number of antigen-presenting cells is higher in these patients [123]. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated the local immune-boosting effects (CTL infiltration with enhanced cytotoxicity) of transarterial chemoembolization [124]. Future studies should reveal the precise effects of locoregional treatments, such as transarterial chemoembolization, transarterial radioembolization, radiofrequency ablation, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, on TAMs in the TME of HCC.

RT has local immune-modulatory effects in HCC. Some studies have reported that irradiation hinders tumor growth and triggers the ongoing mobilization of F4/80+ CD68+ macrophages to irradiated tumors [125]. This stimulates TNF-α and IL-6 production and an inflammatory response [125]. In murine models, lung metastasis was reportedly prevented and survival improved when irradiation was delivered with intravenously administered recombinant macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1α) [126]. Further research is required to determine the effect of RT on TAMs in the TME.

The synergistic effects of RT and ICIs are highlighted by numerous preclinical studies. Many ongoing clinical trials are testing the efficacy of this combined approach [127]. The abscopal effect, which describes the regression of tumors outside the RT field, may be boosted by the combined use of ICIs [128]. A recent study using a syngeneic murine model of HCC demonstrated potential abscopal effects with the increased infiltration of CTLs in both irradiated and nonirradiated tumors [128]. The RT-ICI combination is also identified as a potential HCC treatment based on an observed correlation between soluble PD-L1 levels after RT and patient prognosis [129].

Multi-TKIs

For patients with stage C or B BCLC who are not suitable for local or surgical treatment, systemic therapies are recommended as a first-line treatment [1]. The recent randomized phase 3 trial REFLECT demonstrated that lenvatinib is noninferior to sorafenib in overall survival in treatment-naïve unresectable HCC [130,131]. Additionally, lenvatinib had better progression-free survival compared to sorafenib as a salvage therapy for transarterial treatment [132]. This result may be due to the immune-modulatory effects of lenvatinib [57]. The immune-regulatory activity of lenvatinib is an important determinant of its antitumor effect. This activity is mediated by a reduction in TAMs and an increase in intratumoral CD8+ T cells [133]. Lenvatinib also improves the therapeutic impact of ICIs by a localized reduction in TAMs [134]. PD-L1-expressing macrophage infiltration was recently demonstrated to be a potential predictor of the response to lenvatinib in unresectable HCC [57]. PD-L1+ TAMs may represent tumor immunogenicity and may be targeted by ICIs and lenvatinib [57].

Considerable resistance to sorafenib is afforded by TAMs with an M2 phenotype via the production of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and activation of HGF/c-Met, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, and PI3K/AKT pathways in tumor cells [135]. In turn, this exacerbates the infiltration of M2-TAMs and generates a positive feedback loop [135]. The number of CCL2+ or CCL17+ TANs correlates with tumor development, progression, and sorafenib resistance, as mediated by TAMs and regulatory T cell recruitment by TANs in HCC [120]. As previously mentioned, monocyte/macrophage mobilization and TAM M2 polarization depend on the CCL2/CCR2 pathway in HCC [49]. Interestingly, blocking this pathway with a specific chemical inhibitor can potentiate the effects of sorafenib by activating the antitumor activity of CTLs [48]. CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 are critical mediators between TAMs and tumor cells in various cancer types [98]. Increased hypoxia after sorafenib treatment results in the increased accumulation of M2 TAMs and regulatory T cells, which is partly mediated by CXCR4 [136,137]. In a murine HCC model, anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was effective only when administered alongside CXCR4 inhibitors when intratumoral hypoxia was caused by sorafenib [136].

Regorafenib and cabozantinib were recently approved as second-line treatments for unresectable HCC. A study recently demonstrated that regorafenib also enhances antitumor immunity by reversing the M2 polarization of TAMs [138]. This provides a theoretical background supporting the use of the regorafenib and ICI combination treatment for HCC [139]. However, for cabozantinib, the combined administration of anti-PD-L1 did not exert synergistic effects in mouse models [140]. The future discovery of novel therapeutic combinations of TKIs and ICIs is expected to improve patient outcomes by regulating the TAM population in the TME of HCC.

Immune-based therapy

Clinical outcomes in HCC have been significantly improved by ICIs. However, the monotherapy has not elicited a response in a large proportion of cases owing to TME heterogeneity in HCC, as mentioned in previous sections. In an analysis of the single-cell landscape of HCC in response to immunotherapy, an increase in tumor heterogeneity was strongly linked to patient survival [141].

As mentioned earlier, compared to M2 macrophages, M1 macrophages display an elevated expression of PD-L1/HLA-DR [52,142,143]. CD68+ CD11b+ (M1) macrophages create an antigen-presenting niche for the differentiation of stem-like, tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, which is necessary to sustain the CD8+ T cell response in human cancers [144]. The expression of PD-L1 in macrophages may act as a marker for an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 response in HCC. The enrichment of PD-L1+ macrophages in the TME is associated with an activated immunity in TME with a considerable CD8+ T cell infiltration and immune-related gene expression, indicating that the tumor may be responsive to immune-based therapy [12,57,110]. TAM activity in HCC is also regulated by the immune checkpoint molecule TIM-3, which is highly expressed on the surface of macrophages and activated by TGF-β in the TME [145]. Other checkpoint ligands are also expressed on TAMs, including PD-L2 and B7-H4, galectin-9, and V-domain Ig-containing suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA) [145,146]. Collectively, TAMs express many checkpoint molecules in the TME of HCC and may be targeted by immune-based therapies.

There are several putative ways to directly deplete TAMs in the TME of HCC. In mouse models of HCC, the proportion of TAMs decreased by the injection of nanoliposome-loaded C6-ceremide, stimulating CD8+ T cells to exert an antitumor immune response [147]. In a murine Hepa1-6 syngeneic tumor model, the number of M2-like TAMs decreased to some extent by the administration of liposome-encapsulated clodronate, leading to a decrease in tumor size, with no impact on the number of M1-like TAMs [148]. Zoledronate is a third-generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate with selective cytotoxicity toward matrix metalloproteinase-9-expressing TAMs and with the ability to impair the differentiation of monocytes into TAMs [110]. Zoledronate treatment enhanced the effects of transarterial chemoembolization by inhibiting TAM infiltration in HCC rat models [149]. However, there is a concern that the general depletion of macrophages in the liver causes a loss of tissue-resident macrophages mediating immune homeostasis and bacterial clearance [110].

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Various clinical trials and real-world data for HCC indicate that immune-based therapy achieves encouraging clinical responses with manageable toxicity profiles. To maximize the therapeutic efficacy of immune-based therapies, TAMs in the TME of HCC are principal targets, because these cells have various crosstalk routes between tumor and other immune cells, resulting in more aggressive tumors unresponsive to treatments. Future HCC immunotherapy strategies should identify new combination approaches using current or potential treatment options targeting TAMs in the TME of HCC for optimal antitumor efficacy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the financial support of the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation in the program year of 2020. This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2021R1C1C1005844). This work was also partly supported by a Young Medical Scientist Research Grant through the Daewoong Foundation (DY20204P).

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

Clec4F

C-type lectin domain family 4 member F

CSF-1

colony-stimulating factor-1

DAA

direct-acting antivirals

DCs

dendritic cells

EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

GPIbα

glycoprotein 1b alpha

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV

hepatitis C virus

HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

HIF1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

ICIs

immune checkpoint inhibitors

IFN-γ

interferon-gamma

IL

interleukin

JAK2

Janus kinase 2

KCs

Kupffer cells

LAG3

lymphocyte activation gene 3

MAIT

mucosal-associated invariant T cell

MDSCs

myeloid-derived suppressive cells

MIP-1α

macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha

MoMfs

monocyte-derived macrophages

MRS

myeloid response score

NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

NK

natural killer

NO

nitric oxide

ORR

objective response rate

PD-L1

programmed death ligand 1

PD

programmed death

PI3Kγ

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma

PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

RT

radiotherapy

STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

SIRPα

signal regulatory protein alpha

SREBP1

sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

TAMs

tumor-associated macrophages

TANs

tumor-associated neutrophils

TGF-β

transforming growth factor-beta

TIGIT

T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains

TIM-3

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

Tim4

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing 4

TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

TLR

toll-like receptor

TME

tumor microenvironment

TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

TREM2

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

VISTA

V-domain Ig-containing suppressor of T cell activation