A case of amoxicillin-induced hepatocellular liver injury with bile-duct damage

Article information

Abstract

Amoxicillin, an antibiotic that is widely prescribed for various infections, is associated with a very low rate of drug-induced liver injury; hepatitis and cholestasis are rare complications. Here we present a case of a 39-year-old woman who was diagnosed with abdominal actinomycosis and received amoxicillin treatment. The patient displayed hepatocellular and bile-duct injury, in addition to elevated levels of liver enzymes. The patient was diagnosed with amoxicillin-induced cholestatic hepatitis. When amoxicillin was discontinued, the patient's symptoms improved and her liver enzyme levels reduced to near to the normal range.

INTRODUCTION

Amoxicillin is a rare cause of drug-induced liver injury.1-3 Clinical course of hepatocellular injury by amoxicillin is usually benign. The abnormalities resolve within a few months following discontinuation of amoxicillin treatment.

A retrospective study from the United Kingdom estimated that liver injury from amoxicillin occurs in approximately 0.3 cases per 10,000 treated patients.4,5 When identified early and treated appropriately, the prognosis is excellent. However, because of its low occurrence, amoxicillin-induced liver injury has sometimes been overlooked. In such cases, severe injury and even death have been reported due to progressive liver failure and hepatic bile duct injury.6

We report a case of a 39-year-old woman who developed cholestatic hepatitis with bile duct damage and hepatocellular injury following amoxicillin treatment for abdominal actinomycosis.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old woman with no significant clinical history was admitted to the hospital with a distended abdomen and weight loss. The physical examination revealed abdominal distension, abdominal tenderness, and rebound tenderness affecting the entire abdomen. The hemoglobin level was 7.3 g/dL (12-16 g/dL); white blood cell count, 12,440/mm3 (4,000-1,000/mm3), with 67.4% neutrophils and 7.3% lymphocytes; and platelet count, 605,000/mm3 (150,000-450,000/mm3). Laboratory data showed total bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL (0.2-1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 17 IU/L (10-40 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 12 IU/L (5-40 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 127 IU/L (35-123 IU/L), and C-reactive protein 11.22 mg/dL (0.5 mg/dL ). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 46 mm/h (0-10 mm/h); the prothrombin time was 17.4 s (9.2-13.4 s), with an INR of 1.53 (0.83-1.2); and the total protein level was 6.5 g/dL (6-8.2 g/dL). Air fluid levels and an obstructive ileus were evident by plain abdominal X-ray. Abdominopelvic computed tomography confirmed a mass surrounded by an abscess in the ascending colon. The patient was referred to the Department of Surgery, and a right hemi-colectomy was performed. The pathology showed findings consistent with actinomycotic abscesses containing sulfur granules, and the patient was diagnosed with abdominal actinomycosis. One month later, the patient was discharged from the hospital with oral amoxicillin (2 g per day), and follow-up was planned in the outpatient clinic.

Eight weeks after discharge, the patient returned to the hospital with nausea and abdominal discomfort. The laboratory findings were: AST, 77 IU/L; ALT, 157 IU/L; and ALP, 100 IU/L. A follow-up visit was planned. The patient was re-admitted to the hospital 14 weeks later, with general weakness, abdominal discomfort, and nausea. However, there were no symptoms associated with idiosyncratic reactions, such as pruritus, arthralgia, urticaria. Laboratory tests showed increased levels of total bilirubin 2.9 mg/dL, AST 371 IU/L, ALT 245 IU/L, and ALP 184 IU/L. On admission, the patient had a blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg, a body temperature of 36.7℃, and a pulse rate of 74/min. Mild right upper quadrant tenderness was present, with no signs of hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, upon physical examination.

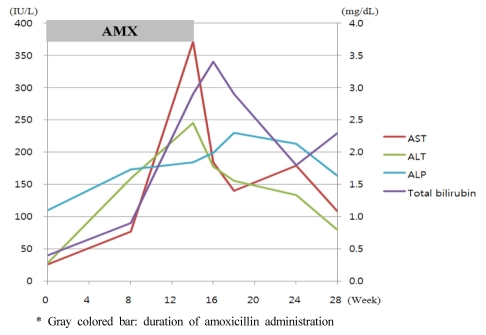

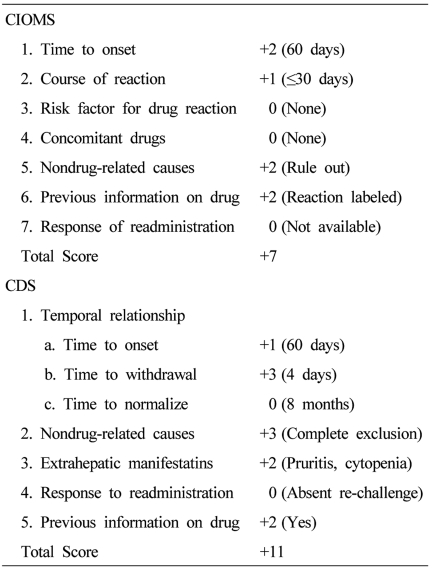

A complete blood count revealed the following: hemoglobin, 11.4 g/dL; white blood cell count, 3,360/mm3; and platelet count, 51,000/mm3. The serum total bilirubin, AST, ALT, and ALP were 2.0 mg/dL, 192 IU/L, 216 IU/L, and 199 IU/L, respectively. The levels of viral hepatitis markers (HBsAg, HBsAb, HBcAb, HAV IgM/IgG, HCV Ab), autoimmune markers (ANA, anti-LKM, AMA, anti-SLA, IgG) were all within normal ranges, and other viral markers were; CMV IgG,, positive; CMV IgM, negative; EBV IgG, positive; EBV IgM, negative; HSV IgG, positive; HSV IgM, negative, suggesting no evidence of viral or autoimmune hepatitis The patient displayed a Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) score were: time to onset, 60 days (+2); course of reaction, within 30 days (+1); non drug-related causes, rule out (+2); previous information on drug, reaction labeled in the product characteristics (+2), making a total of 7 and a Clinical Diagnostic Scale (CDS) score were: time to onset, 60 days (+1); time to withdrawal, 4 days (+3); non drug-related causes, complete exclusion (+3); extrahepatic manifestations, pruritis and cytopenia (+2); previous information on drug, yes (+2), making a total of 11, indicating probable and possible liver damage (Table 1). A liver biopsy was performed, and the pathology showed cholestasis, hepatocellular inflammation, and bile duct damage and loss (nearly 50% in 11/24 portal tracts) (Fig. 1). The patient was diagnosed with cholestatic hepatitis associated with amoxicillin. After discontinuation of amoxicillin, we prescribed Ursodeoxycholic acid 600 mg per day (10 mg/kg) to her. The patient was discharged from the hospital with improved symptoms and laboratory findings. The patient was followed for 14 weeks after discontinuation of the amoxicillin, and all symptoms resolved. The final laboratory findings in the outpatient clinic were: total bilirubin, 2.3 mg/dL; AST, 108 IU/L; ALT, 79 IU/L; and ALP, 163 IU/L (Fig. 2).

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and Clinical Diagnostic Scale (CDS) scores of the patient

Pathology of liver biopsy. (A) Portal inflammation with bile-duct injury. Note the presence of vacuolar degeneration (arrowhead) and necrosis (arrows) of the bile duct epithelial cells (H&E, ×400). (B) Portal tract displaying the absence of the bile duct (H&E, ×400). (C) Hepatic lobule showing mildly fatty changes and cholestasis (H&E, ×400).

DISCUSSION

Drug-induced hepatitis is a common cause of liver injury and acute liver failure, particularly in patients treated with antibiotics.7,8 Amoxicillin causes liver injury in 0.3 of 10,000 prescriptions. However, when prescribed in combination with clavulanate, the incidence of amoxicillin-induced liver injury increases to 1.7 in 10,000 prescriptions.5 The mechanism of amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate hepatotoxicity is unknown. However, the clavulinic acid of amoxicillin/clavulanate combination therapy has been implicated as the cause of hepatotoxicity, as re-challenge with amoxicillin alone is typically well tolerated compared with amoxicillin/clavulanate.5 Furthermore, clavulanic acid combined with other β-lactams can also lead to liver injury.9 Thus, liver injury with these therapies is most likely an idiosyncratic reaction to amoxicillin.

Amoxicillin is an oral semi-synthetic penicillin with a broader spectrum of activity than other penicillins. Amoxicillin distributes to the liver, lungs, gallbladder, and prostate, where it can mildly elevate liver enzyme levels and produce jaundice and abnormalities of bile secretion. Liver injury is a rare side effect of amoxicillin treatment.10,11 Pathology evaluation is helpful for the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury. Severe cases of amoxicillin-induced liver injury, some resulting in death, have been associated with progressive liver failure and the vanishing bile duct syndrome.12,13

In 1996, García Rodríquez et al5 performed a retrospective study of 422,646 individuals to assess liver injury in patients treated with amoxicillin compared with patients treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate in the United Kingdom. Of these individuals, 62,313 received amoxicillin/clavulanate, and 329,213 received amoxicillin alone. Thirty-five individuals presented with acute liver injury: 14 of these cases (0.003%) were among users of amoxicillin alone, and 21 cases (0.017%) were among the users of amoxicillin/clavulanate. Salvo et al14 analyzed a database of the Italian Inter-regional Group of Pharmacovigilance during 2007 to determine the side effects associated with amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate. Amoxicillin/clavulanate-related adverse drug reactions had occurred in 1088 cases; with amoxicillin alone, there were 1095 cases. The percentage of hepatobiliary injury was higher for amoxicillin/clavulanate than for amoxicillin alone. Serious liver injury related to amoxicillin occurred in four cases, which included two with cholestatic hepatitis, one with hepatitis, and one with hepatic necrosis.

In the present case, the patient had no significant medical history and was not receiving any other drug except amoxicillin; there were no significant abnormalities on laboratory testing. There are no specific guidelines for the clinical evaluation to diagnose drug-induced liver injury, but the scales often used for causality include the CIOMS and CDS. In the present case, these scales indicated "probable" and "possible" liver injury, in support of the diagnosis. In addition, the findings of hepatocellular injury, cholestasis, and the loss of bile duct were identified on liver biopsy. Consequentially, the patient was diagnosed with cholestatic hepatitis associated with amoxicillin. The symptoms and laboratory findings improved after the amoxicillin was discontinued.

Compared with the amoxicillin/clavulanate regimen, treatment with amoxicillin alone as a cause for liver injury is rare. In addition, diagnosing drug-induced liver injury is problematic because of its vague symptoms and lack of definite diagnostic guidelines. Amoxicillin is well known as a safe drug even when administered to patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.15 Therefore, amoxicillin-induced liver injury may not be suspected at an early stage, as in the present case. However, when liver injury occurs, hepatocellular liver injury is common.5 In the case reported here, liver biopsy and laboratory findings showed significant bile duct injury and cholestatic hepatitis. The vanishing bile duct syndrome has been reported as a cause of death in a patient with amoxicillin-induced liver injury.6 For most cases of drug-induced hepatotoxicity, the prognosis is good when the drug is discontinued. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that liver failure and death can occur with inappropriate patient management. Thus, patients receiving amoxicillin should be closely monitored for signs of bile duct injury or cholestatic hepatitis resulting from amoxicillin-induced liver injury.

Several current and newly developed drugs can lead to liver injury, but studies investigating drug hepatotoxicity are rare. In the majority of cases, the prognosis is good when administration of the drug is discontinued. However, the administration of well-tolerated drugs such as amoxicillin can lead to liver failure and death in rare cases. Physicians should continue to monitor the potential hepatotoxicity of drugs, even drugs with a very low prevalence of liver toxicity.

Abbreviations

AMX

amoxicillin

AST

aspartate aminotransferase

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

ALP

alkaline phosphatase

INR

international normalized ratio

ANA

antinuclear antibody

LKM

liver-kidney microsome

AMA

antimitochondrial antibody

SLA

soluble liver antigen

CMV

cytomegalovirus

EBV

epstein-barr virus

HSV

herpes simplex virus

CIOMS

Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences

CDS

Clinical Diagnostic Scale