A case of emphysematous hepatitis with spontaneous pneumoperitoneum in a patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma

Article information

Abstract

An 80-year-old woman with hilar cholangiocarcinoma was hospitalized due to sudden-onset abdominal pain. Computed tomography revealed hepatic necrosis accompanied with emphysematous change in the superior segment of the right liver (S7/S8), implying spontaneous rupture, based on the presence of perihepatic free air. Although urgent percutaneous drainage was performed, neither pus nor fluids were drained. These findings suggest emphysematous hepatitis with a hepatic mass. Despite the application of intensive care, the patient's condition deteriorated rapidly, and she died 3 days after admission to hospital. Liver gas has been reported in some clinical diseases (e.g., liver abscess) to be caused by gas-forming organisms; however, emphysematous hepatitis simulating emphysematous pyelonephritis is very rare. The case reported here was of fatal emphysematous hepatitis in a patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

INTRODUCTION

Emphysematous change in the liver can be seen in several clinical situations, such as liver abscesses caused by gas-forming bacteria, after sphincterotomy, and bowel infarction.1-3 Hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation can sometimes lead to gas gangrene of the liver.4,5 Except for these incidental cases, there have been few reports of hepatic parenchymal emphysematous change. Futhermore, clinical outcome is reported to be very poor despite application of aggressive management. Radiologically, the features are similar to those of emphysematous pyelonephritis.6 We recently experienced an extremely rare case of emphysematous hepatitis accompanied in a patient with hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

CASE REPORT

An 80-year-old woman was admitted to Gachon Gil Medical Center due to severe right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain of 2 days, before which she had been diagnosed as hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Fig. 1). An endoscopic retrograde biliary stent was placed for biliary drain-age 2 months prior to the current admission. She had no medical history, such as diabetes mellitus or biliary surgery. Symptoms related to cholangitis were resolved with biliary stenting and her general condition showed improvement. Because of her refusal to undergo surgical treatment, radiotherapy was applied after palliative biliary stenting. Computed tomography (CT) performed for simulating a radiation therapy taken 17 days prior to admission revealed ideal placement of an endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage stent (Fig. 2). She received 9 times of radiotherapy with a total dose of 16.2 Gy (1.8 Gy×9 fractions).

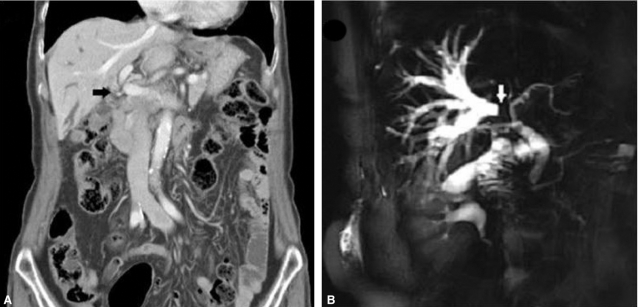

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings on initial diagnosis. (A) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan showing ductal wall thickening with enhancement in the hilar portion of the extrahepatic bile duct (black arrow). Dilatation of the right intrahepatic bile duct without separation of the second-order branch of the right intrahepatic duct was noted, suggesting a type IIIa Klatskin tumor. (B) Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrated severe narrowing of both common hepatic ducts and the right first-order intrahepatic duct (white arrow), with marked dilatation of the right intrahepatic duct, as seen on CT.

CT performed for simulating radiation therapy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan revealing dilatation of the right intrahepatic bile duct without separation of the second-order branch of the right intrahepatic duct. There was no evidence of liver infection. Endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage is also visible (black arrow).

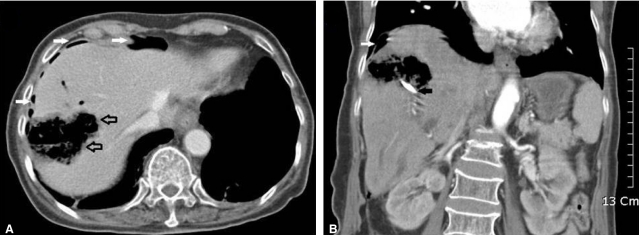

On admission, she was conscious and acutely ill in appearance. Her vital signs included a temperature of 36.7℃, a heart rate of 100 beats/min, a blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 94% on room air. Her sclera was icteric and her liver was palpable approximately 2 cm below the right costal margin. Right upper quadrant tenderness of the abdomen was present. The spleen was not palpable. Initial complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 36,130 mm3, hematocrit of 28.2%, and hemoglobin of 9.3 mg/dL. Blood urea nitrogen was 34.9 mg/dL and creatinine was 1.4 mg/dL. C-reactive protein was 26.56 mg/dL. On liver function tests, aspartate transaminase of 882 IU/L, alanine transaminase of 257 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase of 464 IU/L, and total bilirubin of 17.9 mg/dL. Prothrombin time was normal. Abdominal CT scan demonstrated hepatic parenchymal emphysema measuring approximately 6.3×4.4 cm in the superior segment of the right liver (S7/S8) with pneumoperitoneum finding in the perihepatic space (Fig. 3). Urgent percutaneous drainage was attempted under the peritonitis impression; however, no fluid was drained. A diagnosis of emphysematous hepatitis with spontaneous rupture into the peritoneal cavity was made.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan images taken on emergent admission. (A) Horizontal section. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the upper abdomen demonstrating hepatic necrosis with emphysematous change (open arrow)-a totally emphysematous lesion in the right lobe of the liver. (B) Coronal section. CT scan showing pneumoperitoneum in the perihepatic space (white arrows). The black arrow shows an endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage tube.

On the second day of admission, aggravated laboratory tests were noted as follows: WBC 26,000 mm3, aspartate transaminase 978 IU/L, alanine transaminase 257 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 367 IU/L, total bilirubin 27.4 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 50.2 mg/dL, creatitine 1.2 mg/dL, prothrombin time INR 1.19. Clostridium perfringens and Escherichia coli were grown on blood culture. She was empirically treated with cefotaxime and metronidazol. Despite intensive therapy in the ICU, the patient's condition did not show improvement and she expired on the third day of admission.

DISCUSSION

Intra-abdominal emphysematous infections have not been uncommonly found in many organs, including the urinary tract, gallbladder, uterus, stomach, and pancreas1; however, a few have been found in the liver or biliary system. In liver, emphysematous condition can be seen in pyogenic liver abscesses by gas-forming abscess or after invasive procedures, such as transarterial embolization, radiofrequency ablation, and percutaneous ethanol injection in hepatocellular carcinoma,2,3,7,8 of which cases have been seen only in the portion of the affected lesion. Therefore, emphysematous replacement of a liver is an extremely rare clinical condition.

The usual CT finding of pyogenic liver abscess is clustered or multi-septated lesion with fluid collection of surrounding parenchymal edema.6,9,10 In few cases of gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess, air bubbles or an air-fluid level can be revealed with localization in the involved area. On the other hand, in our case, the affected liver was totally replaced by air with no fluid content.

Another differentiating disease, gas gangrene in the liver, which requires compromise of the both hepatic arterial and portal venous supplies, has been reported in the clinical setting of hepatic trauma or liver transplantation.4,5,11,12 Although parenchymal gas bubbles can be found in these conditions, like our case, parenchymal necrosis with emphysematous change is not feasible and pneumobilia is usually accompanied in cases of gas gangrene. Since both hepatic artery and portal veins were patent on CT scan and there was no history of diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis, differentiation is easily possible.

In addition, our case differs from radiation induced liver disease (RILD). RILD, often called radiation hepatitis, typically occur between 2 weeks to 3 months after therapy.13 Broad guidelines for normal liver dose constraints, for 5% or less risk of RILD, is a whole liver dose of 28-30 Gy in 2 Gy per fraction or a mean normal liver dose (liver minus gross tumor volume) of 28-32 Gy in 2 Gy per fractions.14 The CT findings that favor RILD were seen in areas of low attenuation resulting from either edema or vascular congestion in the target volume that corresponded to the irradiated portion of the liver, a sharp line of demarcation corresponding to the external beam port, usually with an anteroposterior or oblique orientation.15 Our patient received a total dose of 16.2 Gy in 1.8 Gy per fraction and a mean normal liver dose of 6.0 Gy. The last radiation therapy was administrated in the hospital three days ago. In this regard, the possibility of RILD in our case is very rare.

Of particular interest, spontaneous pneumoperitoneum caused by ruptured hepatic lesions in this case was observed in the perihepatic space. Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum of infection in an intra-abdominal organ is extremely rare, and only a few cases have been reported.16

As mentioned in another report, emphysematous hepatitis is similar to the findings of emphysematous pyeolonephritis.6 Empysematous pyelonephritis is classified into two subtypes (types I and II) according to findings on CT scan.17,18 Type I emphysematous pyelonephritis refers to renal parenchymal necrosis with either absence of fluid content or the presence of a streaky or mottled gas pattern and type II refers to the presence of renal or perirenal fluid accompanied by a bubbly gas pattern or gas in the collecting system.17,18 Considering these findings, our case appears to be equivalent to type I emphysematous pyelonephritis and we can diagnose as emphysematous hepatitis.

Late stent blockage by biliary sludge is a major complication. In one study, adherence of Clostrium sp. to the stent occurred as few as 6 days after stent placement and the bacterial density appeared to be proportional to the length of time the stent remained.19 However, the authors reported that though few enrolled patients had symptoms of fever, pain, and leukocytosis at the time of stent removal, most of the patients in their study had no clinical symptoms of biliary infection. Inhibition of growth of Clostridium perfringens by bile acids has been reported.20 In another study of patients who received chemotherapy with a biliary stent, the incidence of stent related complications, such as infection and stent blockage, was not significant.21 Therefore, it is our cautious conclusion that the role of the biliary stent in this case may be very limited.

The clinical outcome of emphysematous hepatitis appears to be fatal, as seen in our case and in other reports.6 Therefore, an aggressive therapeutic modality is emphasized and surgical intervention should not be delayed in patients with emphysematous hepatitis who do not show substantial improvement after intensive medical therapy. Unfortunately, in our case, the rapidly aggravating condition did not provide an opportunity for rescue. In conclusion, we have described a very rare case of emphysematous hepatitis featuring total emphysematous replacement of hepatic prarenchyme, leading to death.

Abbreviations

CT

computed tomography

ICU

intensive care unit

MRCP

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

RILD

radiation induced liver disease

RUQ

right upper quadrant