INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality in the world.

1 HCC mainly occurs in patients with high risk factors including hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and liver cirrhosis (LC).

2 In Korea, where about 5-6% of general population has HBV infection, HCC is one of top three cancers, imposing a significant health problem nationwide.

3

Elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and typical enhancement pattern during dynamic imaging provide critical clues for the diagnosis of HCC.

4,

5 Although sensitivity and specificity of serum AFP as a tumor marker is being challenged, high level or steady-increasing level of serum AFP strongly suggest development of HCC.

6 Arterial hyperattenuation and washout in the portal or delayed phase at contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been accepted as typical enhancement patterns of HCC.

7,

8

Clinical diagnosis of HCC without biopsy is a routine clinical practice,

9 since guidelines by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)

10 and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)

11 have proposed clinical diagnosis of HCC based on a typical enhancement pattern during dynamic imaging and/or elevated serum AFP level in high-risk groups. Usefulness of the clinical diagnostic criteria by Western guidelines has not been fully evaluated in HBV endemic area like Korea except one latest report about validation of AASLD guideline in HBV endemic area.

12 In addition to EASL and AASLD guidelines, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines

13 and the Korean Liver Cancer Study Group and the National Cancer Center (KLCSG/NCC) guideline

14 are also used for management of HCC in Korea. These four clinical diagnostic criteria differ in details of risk factors, cut-off value of serum AFP level, and definition of typical image pattern according to their population of interest. However, there is little data comparing the accuracy of various non-invasive diagnostic criteria for HCC.

Herein, we compared the accuracy and usefulness of these clinical diagnostic criteria in a HBV endemic area.

DISCUSSION

Most guidelines recommend non-invasive criteria for diagnosing HCC. Their usefulness was not fully verified in HBV endemic areas. Moreover, there have been no attempts to compare the accuracy of these guidelines until now. Hence, we compared the usefulness of non-invasive diagnostic criteria by four representative guidelines for management of HCC by EASL, AASLD, KLCSG/NCC, and NCCN. We further analyzed their accuracy according to HBsAg status, accompanying LC, and tumor size in a HBV endemic area.

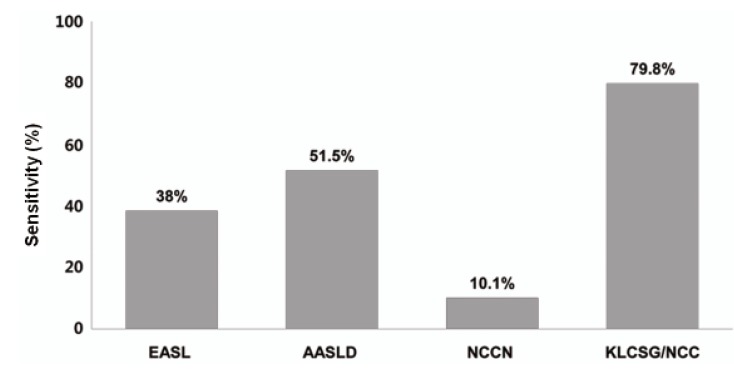

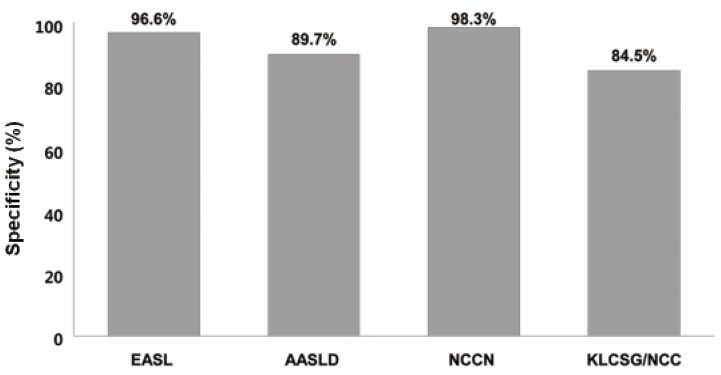

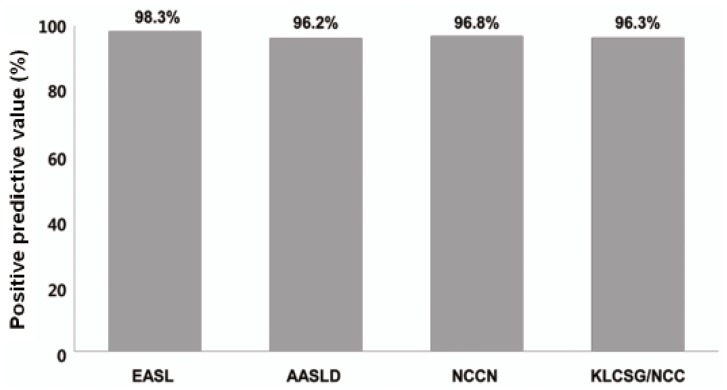

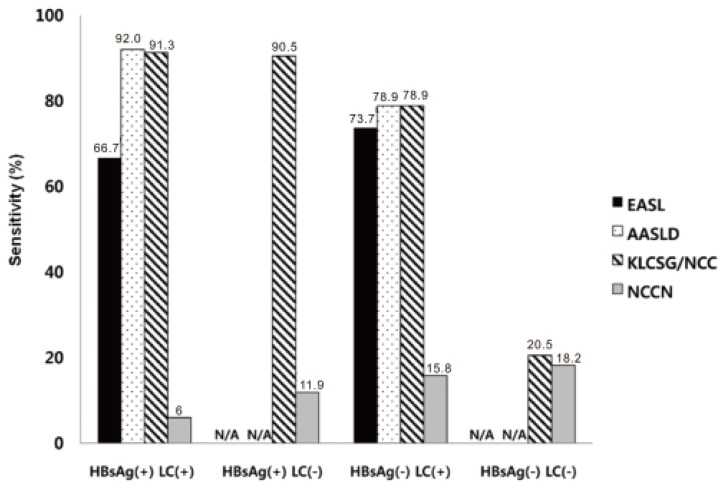

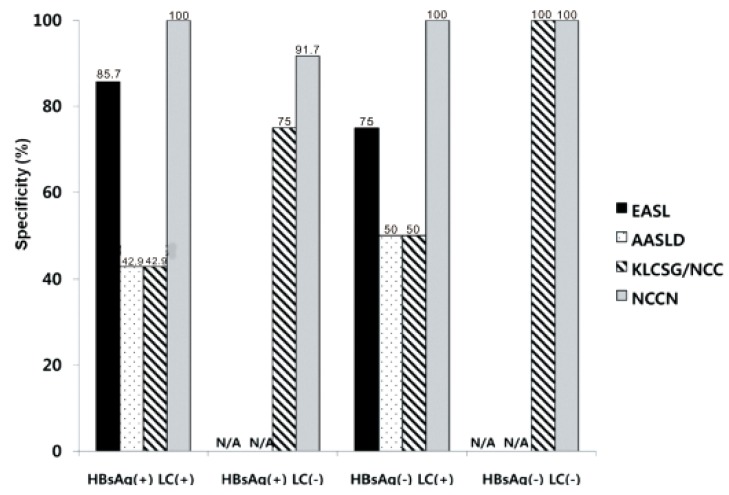

Our study revealed that sensitivity was the highest in KLCSG/NCC criteria (79.8%), followed by AASLD (51.5%), EASL (38.4%), and NCCN criteria (10.1%, P<0.001), whereas specificity (84.5-98.3%) and PPV (96.2-98.3%) were quite similar in the whole patients. Subgroup analysis showed that EASL and AASLD criteria were more sensitive (42.7% vs. 22.2%, P=0.03 for EASL; 59.0% vs. 23.8%, P<0.001 for AASLD) and similarly specific in HBsAg (+) patients than in HBsAg (-) patients. KLCSG/NCC criteria showed higher sensitivity (91.0% vs. 38.1%, P<0.001) but lower specificity (63.2% vs. 94.9%, P=0.03) in patients with HBV infection, compared to those without. Similarly, sensitivity of KLCSG/NCC was higher (89.9% vs. 66.4%, P<0.001) but its specificity was lower (45.5% vs. 93.6%, P<0.001) in LC group than non-LC group. Notably, its sensitivity was 90.5% and specificity was 75% in HBsAg (+) patients without LC. NCCN criteria showed high specificity but very low sensitivity throughout the subgroups.

For all evaluable diagnostic criteria, accuracy was not different according to tumor size.

Three published studies explored the accuracy of non-invasive diagnostic criteria for HCC by comparing pathologic and clinical diagnosis.

12,

18,

19 Kim et al

12 validated AASLD criteria in 206 patients with liver nodules larger than 2 cm. According to this report, diagnosis by AASLD criteria revealed that sensitivity, specificity, and PPV were 89.2%,76.2%, and 93.6%.

Park et al

18 evaluated the accuracy of KLCSG/NCC criteria for clinical diagnosis of HCC in 232 patients with liver nodules of variable sizes (LC=49.1%, HBV infection=73.3%). They reported that overall sensitivity, specificity, and PPV were 95.1%, 73.9%, and 93.7%, repectively. The accuracy was not significantly affected by lesion size or the presence of clinical cirrhosis.

18 Forner et al

19performed a prospective validation of the AASLD criteria in the diagnosis of 89 hepatic nodules Ōēż20 mm in cirrhotics (HCV infection= 76.4%).

19 They reported that sensitivity, specificity, and PPV were 33%, 100%, and 100%, repectively.

In addition, two other studies are noteworthy. Leoni et al

20 evaluated 75 liver nodules in patients with LC (HCV infection=55%, size=10-30 mm). However, biopsy was done only if clinical diagnostic criteria were not fulfilled. Sangiovanni et al

21 explored de novo 67 liver nodules in LC patients (HCV infection=62%). Although histologic findings were available in all patients, fulfillment of the clinical criteria was not evaluated. Hence, accuracy of the non-invasive criteria could not be gained in the previous two studies.

20,

21

While HCC was confirmed in 284 (80.0%) of 355 patients enrolled in this study, final histologic diagnosis were CC in 23 (6.5%), HCC-CC in 13 (3.7%), focal nodular hyperplasia in 10 (2.8%), eosinophilic abscess, abscess, and regenerating nodule. Forner et al

19 reported that 67.4% of patients with liver nodule Ōēż20 mm detected during ultrasound surveillance were proven to be HCC, whereas others were diagnosed with CC (1.1%), regenerative nodules/dysplastic nodules (27.0%), hemangioma (3.4%), and focal nodular hyperplasia (1.1%). According to Sangiovanni et al

21 among 67 liver nodules (1-2 cm in size), 44 (66%) nodules were finally confirmed as HCC, two (3%) as CC, three (4%) as low grade dysplastic nodules, and 18 (27%) as macroregenerative nodule.

21 According to Park et al

18 12 of 189 patients (6.3%) were falsely diagnosed as HCC using KLCSG/NCC criteria; six cases of CC, two of dysplastic nodules, one of focal nodular hyperplasia, two of hamartoma, and one of angiomyolipoma.

18

Among all enrolled patients in this study, KLCSG/NCC criteria showed the highest sensitivity, followed by AASLD, EASL, and NCCN criteria, whereas the specificity of these criteria were quite high and not significantly different between these criteria. The EASL and AASLD criteria were more sensitive and similarly specific in HBsAg (+) patients than in HBsAg (-) patients. KLCSG/NCC criteria showed high sensitivity but low specificity in patients with HBV infection or LC. Different sensitivity and specificity among these criteria according to HBsAg status and presence of LC can be explained by disagreement on detailed clinical definition of HCC among the guidelines as well as unique characteristics of patients included in this study (LC=50.7%, HBV infection=71.3%). EASL, AASLD, and KLCSG/NCC guideline shares common elements for non-invasive diagnostic criteria of HCC but their detailed definition was quite different among the guidelines (

Table 1). First of all, patients with LC are defined as the only risk group in EASL and AASLD criteria, whereas those with HBV and HCV infections are also regarded as a risk group in the KLCSG/NCC criteria. Actually, 84 (87.5%) of 96 HBsAg (+) patients without LC in this study were proven to have HCC, which led to increased sensitivity of KLCSG/NCC criteria. In addition, the cut-off level of serum AFP and image findings required for non-invasive diagnosis are most strict in EASL criteria (except NCCN criteria), followed by the AASLD and KLCSG/NCC criteria. To a certain extent, tendency toward high sensitivity and low specificity of KLCSG/NCC and AASLD criteria might be explained by relatively loose standard for serum AFP level and image findings.

KLCSG/NCC criteria showed higher sensitivity (91.0% vs. 38.1%,

P<0.001) but lower specificity (63.2% vs. 94.9%,

P=0.03) in patients with HBV infection, compared to those without. These findings are constant with the previous reports showing that its sensitivity were 97.3% and 86.8% in the HBsAg potisitive group and non-HBV group, respectively (

P<0.001), and the specificity were 56.5% and 91.3%, respectively (

P<0.001).

19 Remarkably, KLCSG/NCC criteria showed high sensitivity in the HBsAg (+) group regardless of combined LC (91.3% with LC vs. 90.5% without LC). Furthermore, specificity of KLCSG/NCCN criteria in HBsAg (+) LC (-) group is quite acceptable (75.0%) in this study. Hence, it should be positively considered to include HBV-infected patients in risk group for clinical diagnostic criteria of HCC irrespective of LC status in HBV endemic areas.

Expanded risk group and inclusion of small tumors in KLCSG/NCC criteria can explain its high sensitivity in the overall patients and high FPR in HBsAg (-) patients and those with tumor <2 cm. KLCSG/NCC criteria should be applied with caution in those subgroups. In addition, further studies are warranted for evaluation of its accuracy in patient with tumor <1 cm.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing the usefulness of non-invasive diagnostic criteria by the representative guidelines in a HBV endemic area. We showed high sensitivity of KLCSG/NCC and AASLD criteria, compared to EASL criteria, and excellent specificity of all criteria. While EASL and AASLD criteria were more sensitive and similarly specific in HBsAg (+) patients, KLCSG/NCC criteria showed higher sensitivity but lower sensitivity in those with HBV infection or LC. Notably, the KLCSG/NCC criteria showed high sensitivity and acceptable specificity in HBsAg (+) patients without LC. When we compared the usefulness of clinical diagnostic criteria based on sensitivity and FPR, KLCSG/NCC criteria showed acceptable FPR and the highest sensitivity in the overall patients, HBsAg (+) group, LC (-) group, and patients with tumor Ōēź2 cm. Its sensitivity is similar to that of AASLD in LC (+) group (89.9% vs. 90.5%). Hence, inclusion of HBV infection in a risk group of clinical diagnostic criteria for HCC would be reasonable to improve sensitivity with acceptable FPR in HBV endemic areas.

We acknowledge that our study had some limitations as a retrospective study. To a certain degree, our data might be affected by selection bias and personal preference of physicians, even though a concerted effort had been put into keeping consistent diagnostic and therapeutic strategy in our institution. Patients with typical image findings and elevated serum AFP who did not underwent surgery were most likely to be excluded in this study since biopsy were rarely performed for those patients. In addition, patients with multiple tumors were excluded in this study since we can not identify which tumor contributes to elevation of serum AFP level. Despite a few limitations, we investigated a considerable number of patients recruited from a single institution during recent two years, which gives a homogeneous character to this study. Standardized up-to-date techniques for measurement of serum AFP and dynamic imaging

22 and coherent strategy to make decision were adopted for the enrolled patients.

In conclusion, overall sensitivity was high with KLCSG/NCC and AASLD criteria, specificity was excellent with all criteria. Based on sensitivity and FPR, KLCSG/NCC criteria was the most useful one in the overall patients; especially in HBsAg (+) group, LC (-) group, and patients with tumor Ōēź2 cm. Inclusion of HBV infection as a risk factor in clinical diagnostic criteria for HCC would be reasonable to improve sensitivity with acceptable FPR in HBV endemic areas.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print