INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis A is caused by infection with the hepatitis A virus (HAV). The HAV is a non-enveloped, positive-stranded RNA virus that was first identified using electron microscopy in 1973, and is classified within the genus hepatovirus of the picornavirus family.1 Hepatitis A occurs predominantly in children, where it is a self-limiting and usually asymptomatic infection. However, in adults, 75-95% of cases develop jaundice symptoms. The majority of adult patients completely recover within 2 months of disease onset.

While almost all acute hepatitis A infections subside spontaneously without severe complications, some infections can be relapsing, prolonged, and involve cholestasis and acute kidney injury. HAV-induced fulminant hepatitis is rare, with a reported incidence rate of below 0.5%.2 Recently, the incidence of hepatitis A in Korean adults has increased rapidly due to the decreased seroprevalence of anti-HAV. Thus, there is an increasing number of symptomatic adult hepatitis A patients with an unusual clinical course.3

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), is a severe idiosyncratic reaction to drugs, mainly antiepileptics and antibiotics, and can occasionally result in acute liver failure.4 The characteristics of DRESS syndrome include skin rash, fever, lymph node enlargement, and internal organ involvement. Although the pathophysiology of DRESS syndrome remains unclear, it may be due to a defect in detoxification of the causative drug, immunological imbalance, or infections such as human herpes virus type 6 (HHV6).5

The present report describes the case of a 22-year-old male with hepatitis A involving prolonged cholestasis and renal injury who developed DRESS syndrome due to antibiotic and/or antiviral treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of histopathologically confirmed DRESS syndrome following severe relapsing hepatitis A in an adult.

CASE REPORT

In January 2010, a 22-year-old male presented with acute renal failure at another hospital, and was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A. He was treated conservatively at that hospital for one month, during which time the symptoms and laboratory findings improved. At that time he didn't receive any antibiotics. Three days prior to the end of treatment, he developed a sudden fever and liver enzyme levels began rising again. Oseltamivir was prescribed empirically due to the possibility of pandemic swine influenza. One day after the administration of oseltamivir, he developed a whole body skin rash with intense itching. Records from the previous hospital admission indicated a persistent fever accompanied by a skin rash, and an abdomino-pelvic CT showed gall bladder wall thickening. Consequently, cefotaxime and metronidazole antibiotics were prescribed due to the suspicion of acute cholecystitis just one day before his arrival at our hospital.

The patient was referred to our hospital on February 9th due to the cholestatic hepatitis A, fever and skin rash symptoms. The initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 112/72 mmHg, heart rate 113/min, respiratory rate 20/min, and body temperature 38.0℃. Laboratory findings showed a white blood cell count of 15,900/mm3, a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL, a platelet count of 321,000/mm3, an eosinophil count of 2,150/mm3 (8% [upper limit of normal (ULN) 7%]), a serum protein level of 5.0 g/dL, a serum albumin level of 1.9 g/dL, a serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 152 IU/L (ULN 40 IU/L), a serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 187 IU/L (ULN 40 IU/L), a serum creatinine level of 1.3 mg/dL (ULN 1.4 mg/dL), a serum total bilirubin level of 25.8 mg/dL (ULN 1.2 mg/dL), a serum direct bilirubin level of 15 mg/dL (ULN 0.5 mg/dL), and a prothrombin time (PT) (%) level of 22.4% (normal, 70-140%). The patient tested negative for herpes virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B and C, and positive for IgG antibodies against the Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and HAV. The patient also tested positive for anti-HAV IgM.

The patient was treated using conservative management for the hepatitis A with prolonged cholestasis, including the administration of cefotaxime for 4-5 days for the persistent fever and jaundice.

By the 4th day after admission to our hospital, the fever and skin rash symptoms worsened, prompting a skin biopsy (Fig. 1A, B). The biopsy revealed perivascular lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltration, consistent with drug eruption (Fig. 1C). After the 8th day of admission, a liver biopsy was performed to identify a possible cause of the fever. That biopsy revealed an eosinophilic microabscess (Fig. 1D). The peripheral blood eosinophil count was 32.4% (6,059/mm3), and laboratory findings showed a total bilirubin level of 23 mg/dL, an AST level of 110 IU/L, an ALT level of 142 IU/L and a serum creatinine level of 4.4 mg/dL.

Upon consideration of the overall findings, we made a diagnosis of DRESS syndrome and prolonged cholestatic hepatitis A with renal azotemia. Therefore, cefotaxime administration was immediately ceased, and high-dose steroid (hydrocortisone 80 mg tid daily) and immunoglobulin (1 g/kg/day for 2 days) were administered. After a week of high-dose steroid administration, the fever and skin rash improved, and prednisolone was then continued at a maintenance dose.

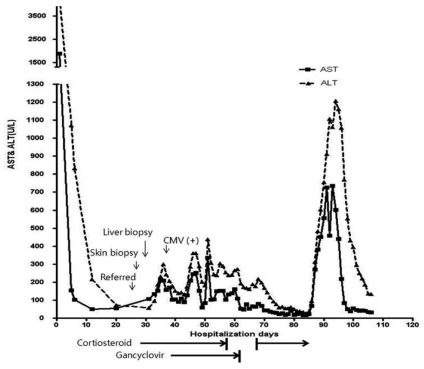

After 20 days of treatment, the fever recurred. A CMV antigenemia test returned positive findings (41/200,000 WBC), and a CMV PCR showed 1,097,500 copies/mL. The steroid dose was rapidly reduced and ganciclovir was administered (Fig. 2). The steroid was discontinued on March 28th, and ganciclovir was ceased on April 7th.

Approximately 10 days after steroid discontinuation, the serum ALT level rapidly rose to 1,200 IU/L. The patient developed another fever and the PT level decreased to 53.9%. We performed further blood cultures and PCR assays for the detection of HAV, CMV and EBV, yet these tests all returned negative findings. This led us to suspect recurrent DRESS syndrome. Therefore, we commenced steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) on April 14th. The patient improved and the steroid dose was tapered gradually such that it was 20 mg daily in the form of oral prednisone by the time of discharge on April 28th. The prednisone was further tapered to 10 mg/day at the outpatient clinic. A review in July 2010 showed that liver functions had normalized.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of acute hepatitis A in adults has increased rapidly during the past 10 years in Korea. The clinical manifestations of this infection range from asymptomatic to fulminant hepatitis. Less than 30% of infected children are symptomatic, while approximately 80% of infected adults manifest severe hepatitis with markedly elevated liver enzymes. Most patients recover uneventfully. However, recently in Korea, the incidence of unusual patterns of severe hepatitis and renal insufficiency has increased as the age of patients with acute hepatitis A has increased.3

The unusual clinical manifestations of acute hepatitis A include protracted cholestasis, relapse and complications involving renal failure.6 Relapsing hepatitis A occurs in 3-20% of acute hepatitis A patients,7 and is characterized by a biphasic or polyphasic peak of liver enzyme elevation. Relapses occur some weeks or months after the apparent recovery, and are marked by the return of symptoms and liver enzyme abnormalities. It generally takes less than 3 weeks for a patient to recover from a recurrent episode. In most cases, transaminases and bilirubin levels usually show a marked decrease but not a complete normalization during this period. The symptoms are usually milder in a relapse episode, although cholestasis can occur.8,9

The current patient first presented at another hospital with renal azotemia, and was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A. Over a treatment period of 4 weeks, the transaminase levels showed marked improvement, although they never completely returned to normal levels. This patient's recurrent episode developed with more severe symptoms than the initial episode, possibly due to the development of DRESS syndrome.

Extrahepatic manifestations are unusual in hepatitis A, and renal manifestations are even less common. Acute kidney injury complicating non-fulminant hepatitis A is reported to occur in only 1.5-4.7% of hepatitis A patients.2 Kidney injury may be the result of direct renal toxicity due to increased bilirubin levels, cryoglobulinemia, alterations in renal blood flow due to endotoxemia, and peripheral immune complex-mediated damage. In the cholestatic variant of hepatitis A, while transaminase levels reduce to normal levels, bilirubin levels increase to above 15 mg/dL, and may persist in that range for more than 8 weeks. This variant can be characterized by pruritus, persistent anorexia, diarrhea and weight loss.10 Although corticosteroids hasten the resolution of prolonged cholestatic hepatitis A, they may predispose to hepatitis relapse.11

In the current patient, the bilirubin level decreased and normalized after the administration of corticosteroid. However, symptoms returned following the cessation of steroid treatment, which is not generally observed when corticosteroids are used to treat recurrent hepatitis A.8 Hence, we considered that the patient was experiencing DRESS syndrome recurrence rather than hepatitis A recurrence. The DRESS syndrome recurrence accompanied an increase in transaminases but not bilirubin levels.

The detection of HAV RNA in the plasma after 20 days of illness is a predictor of prolonged cholestasis, but it is not a predictor of relapsing hepatitis.12 Acalculous cholecystitis may often be a hepatitis A complication, as in the present case, and often manifests transiently with spontaneous recovery.2 The current patient presented with various forms of atypical manifestations associated with acute hepatitis A, including cholestasis and renal injury.

DRESS syndrome is a severe delayed hypersensitivity drug reaction that manifests 2-8 weeks after exposure to the triggering drug. Our patient was diagnosed with DRESS syndrome according to the definition of Bocquet et al.13 The diagnostic criteria include the simultaneous presence of 3 conditions: 1. Drug-induced skin eruption. 2. Eosinophilia (>1,500/µL). 3. At least one of the following systemic abnormalities: enlarged lymph nodes, hepatitis (transaminases >2 ULN), interstitial nephropathy, interstitial lung disease or myocardial involvement. The hypersensitivity reaction is associated with high levels of IL-5 and eosinophil accumulation, and may justify the use of steroids. A recent report suggests that certain drugs may stimulate a massive expansion of drug-specific cytotoxic T cells that destroy hepatocytes via a cell-contact-dependent mechanism.14 Liver involvement in DRESS syndrome is common and may range from a transitory increase in liver enzymes to liver necrosis with fulminant hepatic failure.4 The overall mortality in DRESS syndrome is approximately 10%.15 DRESS syndrome occurs frequently with concomitant viral infection, especially HHV6.16 It may be that viruses interfere with the clearance of the triggering drug and thus induce accumulation of a metabolite.

In the present case, it is still unclear whether DRESS syndrome followed acute hepatitis A or developed simply after receiving the antibiotics and antiviral agent. The association of hepatitis A virus and DRESS syndrome has not been reported elsewhere. However, hepatitis A virus infection appeared to have triggered DRESS syndrome development by reducing the hepatic clearance of drugs, leading to an accumulation of drugs and their metabolites. In a type of feedback loop, it then appeared that the DRESS syndrome caused the recurrent hepatitis symptoms to be worse than the initial symptoms. At this stage we are unable to identify which drug triggered the DRESS syndrome. Our future plan is to perform patch tests using oseltamivir, cefotaxime and metronidazole to identify the causative drug once prednisone treatment is ceased. The in vitro lymphocyte toxicity assay and lymphocyte transformation test also might be helpful. We have recommended that the patient avoid exposure to those drugs.

A recent report showed that the most common causes of DRESS syndrome in Korea were antibiotics, followed by anticonvulsants.17 This may reflect that antibiotics may be being over-prescribed in Korea. To date, the only undisputed treatment for DRESS syndrome is prompt withdrawal of the offending drug. Systemic corticosteroid administration is particularly recommended in patients with life-threatening visceral manifestations that do not respond to drug withdrawal.18 As in the present patient, others have reported cases where DRESS syndrome recurred after a short period of steroid treatment, which has led some investigators to suggest that high-dose systemic steroid may be helpful, and that tapering should then be performed slowly.4

The final diagnosis in the present case was DRESS syndrome due to antibiotic and/or antiviral treatment following hepatitis A with cholestatic features and renal injury. There has been only one previous report of a histopathologically confirmed case of DRESS syndrome following hepatitis A, and that was in a child.19 To our knowledge, the present report is the first to describe a histopathologically confirmed case of DRESS syndrome following severe cholestatic hepatitis A in an adult.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print