INTRODUCTION

During the paracentesis, left lower quadrant of abdomen, especially the site 4 or 5 cm medially apart from anterior superior iliac spine, is a common site used for needling.1,2 If the paracentesis is performed under the sterile condition with appropriate manner, complications such as infection, bleeding and perforation rarely occur and usually have relatively good prognosis which need only supportive care.3,4 Inferior epigastric arteries originated from external iliac artery go up to umbilicus and across the inguinal ring. It can be often injured by invasive procedure, like as paracentesis, retension suture, or peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion or removal. Once the inferior epigastric arteries and its branches are injured by invasive devices, direct hematoma or hemoperitoneum can occur in an instant or late pseudoaneurysm formation and its rupture. Although the paracentesis is considered a less invasive method comparing with other procedures, it is the second most common reason for inferior epigastric artery injury following abdominal retension suture.5 Main reasons can be suspected following two; first, paracentesis is performed repetitively at the similar site, left lower quadrant which might be the course of inferior epigastric artery. Second, paracentesis is mainly indicated for the patients with advanced liver cirrhosis who could have sufficient collateral vessels with increased chance of injury and coagulopathy with thrombocytopenia.

To date, the cases of the injury and rupture of inferior epigastric arterial pseudoaneurysm owing to repetitive paracentesis have been reported. However, the case of bleeding by direct injury of native inferior epigastric artery without aneurismal formation has not been reported.6 We here report a case of patient with advanced liver cirrhosis who was developed a huge abdominal wall hematoma by therapeutic paracentesis and was treated successfully with transcatheter coil embolization of left inferior epigastric artery.

CASE REPORT

A 46 year-old-female patient with advanced liver cirrhosis and refractory abdominal ascites visited Hepatology Department because of progressive abdominal distension and 4 kg weight gain accompanying orthopnea. She was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis 8 years ago. In recent years, according to progression of liver cirrhosis, ascites could not be easily controlled by intensive diuretics and low salt diet. She had drunk 80g of alcohol per day. At the admission, the vital signs were stable with 120/70 mmHg of blood pressure, 80 beat per minute of heart rate, 20 per minute of respiration rate and 36.2Ōäā of body temperature, in spite of chronically ill looking appearance. Physical examination showed icteric sclera and jaundiced face and body and inspiratory rale on chest. Abdomen was severly distended with the shifting dullness and easily restored omphalocele. Tenderness on epigastrium and pretibial pitting edema were also observed.

Laboratory findings showed white blood cell 4,070 /mm3, hemoglobin 11.1 g/dL, platelet 54,000 /mm3, prothrombin time INR 1.66. Biochemical tests showed sodium 136 mEq/L, potassium 3.8 mEq/L, aspartate aminotransferase 201 IU/L, accelerated life test 53 IU/L, total bilirubin 7.14 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 4.42 mg/dL, total protein 8.0 g/dL, albumin 2.7 g/dL, and ammonia 44 umol/L. Roentgenograms of chest and abdomen showed mild pulmonary congestion and abdominal distension.

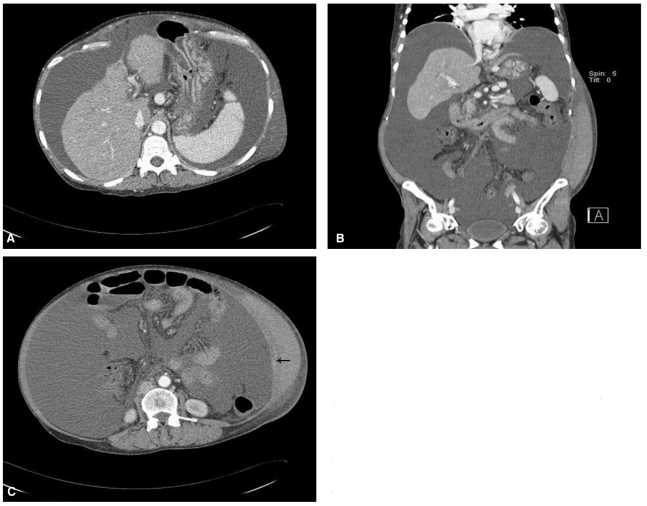

She was diagnosed with diuretics refractory ascites and planned to be performed the therapeutic paracentesis on the day of visiting. After the percussion and palpation of left lower abdomen, the site medially 4 to 5 cm apart from the anterior superior iliac spine was punctured by 18 gauge needle catheter which is inserted with drawing imaginary Z-line, following the runs of abdominal muscle fibers. Initially approximately 20 mL was aspirated by syringe, after the assurance of the serous ascites, catheter was connected with infusion set, and about 6 liters of ascites were naturally drained. Right after the drainage, vital signs were stable and there was no complication including bleeding. For stabilization of hemodynamics, a bottle of 20 percent albumin solution 100 cc was infused, immediately. At the one day after the paracentesis, the patient complained the severe lower abdominal pain. The left lower quadrant of abdomen was discolored to slight bluish and huge abdominal mass like lesion around the puncture site was palpated without pulse or tenderness. Vital signs were blood pressure 100/60 mmHg, pulse rate 100 beat per minute, respiration rate 24 per minute, body temperature 36.7Ōäā. Laboratory findings revealed hemoglobin down to 7.1 g/dL, suggesting the acute bleeding. Under the suspicion of paracentesis induced hemoperitoneum or hematoma of abdominal wall, abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed with transfusion of packed red cells and fresh frozen plasma. The abdominal CT showed massive ascites without the evidence of hemoperitoneum (Fig. 1A). About 22 cm ├Ś 16 cm sized hematoma at left lower abdominal wall was detected (Fig. 1B). A contrast enhancement seen in the abdominal wall suggested muscular arterial injury with contrast leak (Fig. 1C).

Two days after paracentesis, despite massive transfusion, with the 3 pints of packed red blood cells and 2 pints of fresh frozen plasma, hemoglobin was still 7.2 g/dL and the abdominal hematoma seemed to be more expanded than the day before. An urgent transcatheter angiography with embolization was performed. After the puncture of right femoral artery, the introducer sheath was located on abdominal aorta. When the contrast media passed the left external iliac artery and its daughters, left inferior epigastric artery and left circumflex artery via the pig tailed catheter (Fig. 2A), the extravasation from left inferior epigastric artery and its branches was detected (Fig. 2B). Through the superselection with microcathter, two of 3 mm ├Ś 2 cm sized coils, one of 5 mm ├Ś 2 cm sized coil and one of 6 mm ├Ś 2 cm sized coil were implanted at the branches of left inferior epigastric artery. The leak of contrast media was not observed after the procedures (Fig. 2C).

Two days after the coil embolization, the vital signs and hemoglobin level were stabilized, and the size of the hematoma was decreased. However, total bilirubin increased up to 10.0 mg/dL, serum ammonia was 66 umol/L, the grade I hepatic encephalopathy was developed and the patient was treated with lactulose enema and nutritional support. At the 13th day after embolization, the patient was discharged with improvement of hepatic encephalopathy.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of ascites in liver cirrhosis is mainly a medical therapy, such as salt restriction and diuretics. Refractory ascites in advanced stage of liver cirrhosis is indicated for repetitive therapeutic paracentesis, transjugular intrahepatic shunt (TIPS), or liver transplantation. However, under the donor limitation for liver transplantation and the risk of hepatic encephalopathy of TIPS, repetitive paracentesis is a practical option for the control of a refractory ascites.1-2,7,8

The left lower quadrant of abdomen 4 or 5 cm medially apart from anterior superior iliac spine is commonly used for needling in paracentesis. Besides left lower quadrant of abdomen, the center of median line from umbilicus to pubis and right lower quadrant of abdomen would be used for puncture site, but left lower quadrant is more preferred than the other sites owing to low vascularity of the lesion and relatively thin abdominal wall, comparing with the right side.1-2,7-10 Needling should be entered according to the direction of abdominal muscle fiber, with drawing a imaginary Z-line.11 After the large volume paracentesis above 6 liter, parenteral fluid should be resuscitated as volume expander, such as albumin. Generally, under the sterile condition and appropriate manner, paracentesis induced complications are rare with relatively good prognosis. Only in extremely rare cases, complications can be progressed scathingly. The incidence of fatal bleeding defined as the situation needs special procedure, intervention or urgent operation is approximately 0.2 percent per procedures, and the incidence of mortality due to bleeding complication is lower than 0.01 %.7 In a prospective study of De Gottardi et al1, the incidence of massive bleeding was approximately 1.0% (5/515), the patients of massive bleeding was treated with embolization or emergent operation. In univariate analysis, most important factor for massive bleeding is the disease status of patient with liver cirrhosis, especially Child-pugh class C and thrombocytopenia lower than 50,000 /mm3. In our case, the Child-pugh class of the patient was also class C and platelet count was initially 54,000 /mm3.

Anatomically inferior epigastric arteries are originated from external iliac artery and across the inguinal ring and go up to umbilicus. Within abdominal muscle, inferior epigastric arteries go by transversalis fascia and linea semicircularis, ultimately arrived between rectus abdominis muscle and posterior lamella.11 Because the inferior epigastric arteries locate in a relatively superficial layer of abdominal muscle, these are fragile to injury by invasive procedures of abdomen, such as suture, paracentesis. Distinctively the paracentesis is usually performed based on physician's subjective decision under own physical examination, erroneous procedure and malposition of catheter can occur. Therefore one of the efforts to minimize the complications should be "awareness of run of epigastric artery and consideration about the possible injury of inferior epigastric arteries".

Before paracentesis, careful physical examination should be conducted; by palpation of the rectus abdominis muscles, the runs of epigastric arteries should be estimated and by inspection, grossly larger ones of collateral vessels putted superficially should be avoided. Besides, in the patients with prior abdominal wall hematoma or hemoperitoneum, as the paracentesis complications, ultrasound guided paracentesis would be more proper procedure for the avoidance of large, torturous inferior epigastric arteries and pre-formed pseudoaneurysm.6

In the situation that either inferior epigastric arteries or preformed pseudoaneurysms are injured, typically pulseless abdominal mass with tenderness would appear accompanying the significant change of hematocrit, suggesting the vessel injury and hematoma. However, in the majority of the cases, specific signs for bleeding would not appear except nonspecific abdominal pain and often make the clinicians misdiagnose subcutaneous hematoma which is simply developed. For diagnosis of injury of inferior epigastric arteries including pseudoaneurysm, Doppler ultrasonography (US), spiral abdomen CT, and transcatheter angiography are available. Doppler US has several advantages for excluding the pseudoaneurysm by estimation of the blood flow velocity, its origin. Moreover, Doppler US is used for treatment by compression of the lesion during sonographic examination. However, the objective information for hematoma, pseudoaneurysm might not be offered by Doppler US, it would be indicated in limited cases. Comparing with Doppler US, spiral abdomen CT has much of strength for the assessment of size and status of hematoma or hemoperitoneum and for excluding other complications. Transcatheter angiography is usually performed after other noninvasive imaging modality such spiral CT or Doppler US for achieving of both of diagnosis and therapeutic goal. However, when the single modality among spiral abdomen CT, Doppler US and transcatheter angiography is even performed, it is often difficult to diagnose the atypical case or small sized pseudoaneurysm. Therefore several modalities including Doppler US, spiral CT and transcatheter angiography are needed for accurate diagnosis.6

Depending the severity of bleeding, inferior epigastric arterial injury and pseudoaneurysmal bleeding can be treated with all of vessel ligation under the open laparatomy, transcatheter coil embolization, percutaenous thrombin injection via Doppler US and US guided compression against the lesion.6 In the treatment of relatively small sized hematoma of pseudoaneurysm, Doppler US guided thrombin injection or direct compression seemed to be safe and efficient. Virtually the risk for failure is relatively high due to the difficulty of targeting and insufficient compression. Ferrer et al11 recommended vessel ligation under the open laparatomy for the case of huge hematoma with massive bleeding and transcathter coil embolization for the case of small sized hematoma. However in such our case of advanced liver cirrhosis, risk for operation would be high due to deterioration of liver function even if huge hematoma or hemoperitoneum.

Seo et al12 has reported the case of pseudoaneurysm of circumflex iliac artery and inferior epigasatric artery induced by paracentesis in a patient with advanced liver cirrhosis and recommended that the the transcatheter coil embolization is proper for therapeutic modality. Unlike that case, we report the case of huge hematoma induced by injury of native inferior epigastric artery and its branches was treated with transcatheter coil embolization. Even a few cases of inferior epigastric artery related bleeding, in the cases of massive bleeding in the patient with advanced liver cirrhosis, transcatheter coil combolization is more useful and safer than open laparatormy in the view of complications from general anesthesia, exploration failure, operation related infection.

In this case, a huge abdominal wall hematoma developed by therarpeutic paracentesis in the patient with advanced liver cirrhosis, was diagnosed with spiral abdomen CT and treated with transcatheter coil embolization. Our case suggests the importance of anatomical information and run of abdominal wall vessels. The prognosis of the complication can be poor depending the coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia and degree of the portal hypertension, even the risk of procedure related complication is relatively low. In conclusion, physicians performing paracentesis should be aware of its bleeding complication would manifest fatal condition and should struggle for prompt diagnosis and adequate treatment like as transcathter embolization.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print