Peliosis hepatis presenting with massive hepatomegaly in a patient with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Article information

Abstract

Peliosis hepatis is a rare condition that can cause hepatic hemorrhage, rupture, and ultimately liver failure. Several authors have reported that peliosis hepatis develops in association with chronic wasting disease or prolonged use of anabolic steroids or oral contraceptives. In this report we describe a case in which discontinuation of steroid therapy improved the condition of a patient with peliosis hepatis. Our patient was a 64-year-old woman with a history of long-term steroid treatment for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura . Her symptoms included abdominal pain and weight loss; the only finding of a physical examination was hepatomegaly. We performed computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver and a liver biopsy. Based on these findings plus clinical observations, she was diagnosed with peliosis hepatis and her steroid treatment was terminated. The patient recovered completely 3 months after steroid discontinuation, and remained stable over the following 6 months.

INTRODUCTION

Peliosis hepatis is a rare vascular disorder that is characterized histologically by blood-filled cystic cavities that range in diameter from less than one to several millimeters; these cavities are scattered throughout the liver parenchyma.1 The cystic lesions are often irregularly shaped and in many cases are incompletely lined with endothelium.2 Peliosis hepatis is found in association with wasting disease, liver and renal transplantation, hematologic malignancy,1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,3 advanced tuberculosis,4 bartonella infection,4 and many drugs including anabolic steroids5 and oral contraceptives.6 Peliosis hepatis varies from minimal asymptomatic lesions to massive lesions that may present with cholestasis, hepatic failure, or spontaneous rupture requiring liver transplantation.78910 As the differential diagnosis of subacute liver masses is complex, and benign and malignant/pre-malignant lesions share overlapping imaging characteristics, peliosis hepatis is very difficult to diagnose.

This case study will discuss and analyze the medical history of a patient diagnosed with peliosis hepatis that was likely caused by long-term steroid exposure. The case illustrates resolution of the condition after withdrawal of the offending medication, fortunately before the development of any serious complications.

CASE REPORT

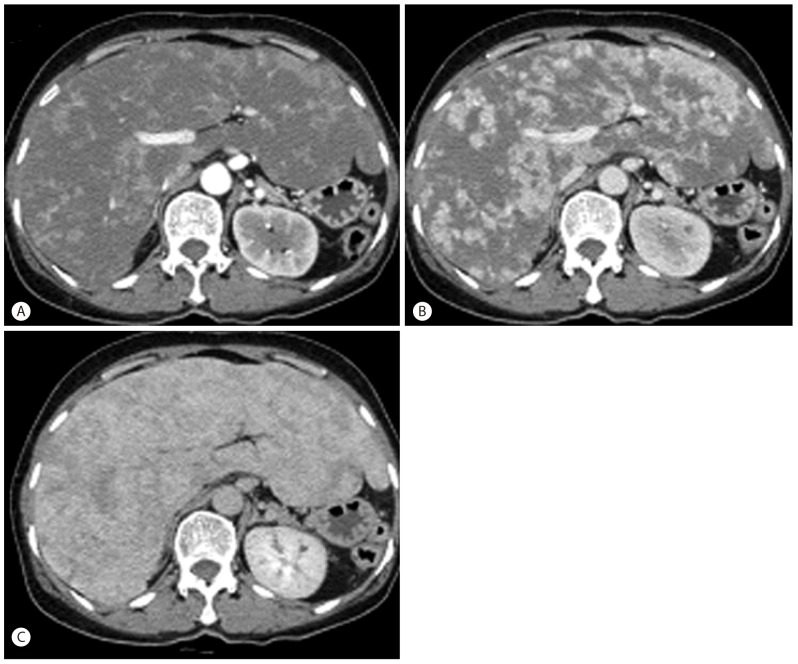

A 64-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for unexplained weight loss of six kg over the past year. Her past medical history included idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) 3 years ago that was treated with long-term corticosteroid therapy. The patient complained of nonspecific epigastric pain and a feeling of abdominal distension. Her vital signs showed a blood pressure of 147/76 mm Hg, a heart rate of 78 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and a temperature of 37℃. Physical examination revealed a firm, non-tender liver edge palpable two cm below the right costal margin. Exam revealed no other findings such as jaundice, cutaneous stigmata of chronic liver disease, ascites, or splenomegaly. Laboratory examination showed a white blood cell count of 5.6 × 109/L (normal 4 × 109-10 × 109), a hemoglobin of 11.2 mg/dL (normal 13.1-17.5 g/L), a hematocrit of 29% (normal 39-52%), a platelet count of 34 × 109/L (normal 140 × 109-400 × 109 /L), an alkaline phosphatase of 163 IU/L (normal <220 IU/L), an alanine aminotransferase of 32 IU/L (normal <43 IU/L), an aspartate aminotransferase of 44 IU/L (normal 38 IU/L), and a prothrombin time of 13.5 seconds (normal 11-15 seconds). Serologic markers and acid fast bacilli (AFB) level were within normal limits. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) images obtained in the late arterial and portal venous phases showed heterogeneous enhancing lesions infiltrating the hepatic parenchyma with a mosaic pattern of perfusion (Fig. 1).

Axial contrast-enhanced CT images. (A, B) Axial contrast-enhanced CT images obtained in the late arterial and portal venous phases show heterogeneous enhancement of the hepatic parenchyma with a mosaic perfusion pattern. (C) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image obtained in the equilibrium phase shows progressive enhancement isoattenuating to vessels.

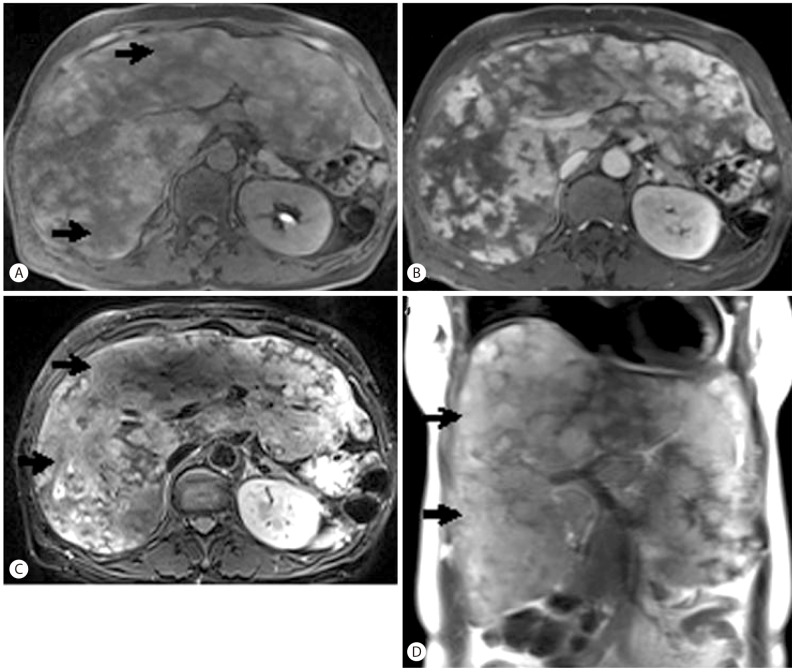

Liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed marked enlargement of the liver, with diffuse infiltrative lesions and collapse of the inferior vena cava and hepatic vein (Fig. 2). This suggested an infiltrative disease of the liver parenchyma such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or multiple abscesses. However, there was no sign of a mass effect or vascular thrombosis despite extensive lesions dominating the liver parenchyma. The lesions with high signal density on T2-weighted images suggested a possible diagnosis of malignancy such as HCC. However, lesions with bright T2-weighted signal intensity and persistent enhancement on delayed-phase CT and MRI instead suggested peliosis hepatis.

Transverse contrast-enhanced MRI. (A) Transverse T1-weighted MRI image obtained before injecting contrast material depicts ill-defined hypointense lesions in both liver lobes (arrows). (B) Transverse contrast-enhanced MRI image obtained in the portal venous phase shows heterogeneous enhancement of the hepatic parenchyma. (C) Axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted MRI image and a coronal heavily T2-weighted MRI image show hepatomegaly and multiple ill-defined lesions with heterogeneous signal intensities in both liver lobes (arrows).

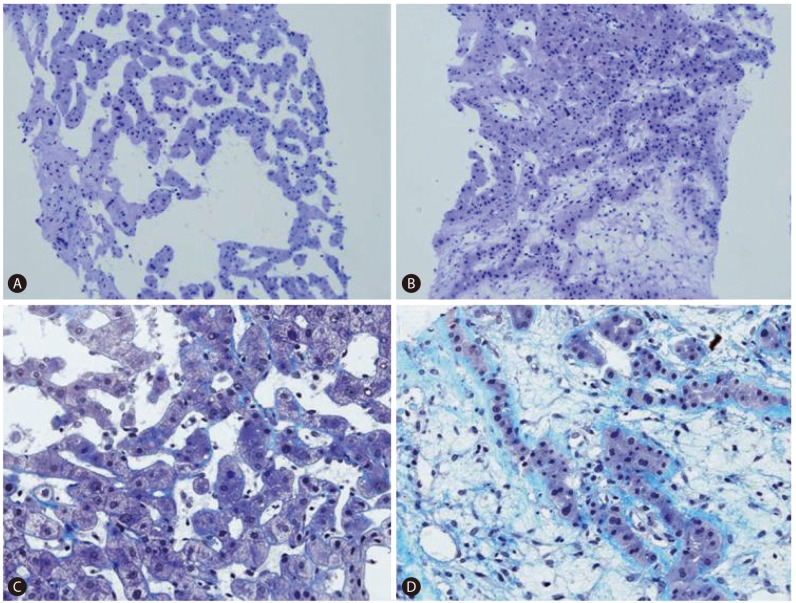

To verify the diagnosis, we performed an ultrasound-guided gun biopsy. Histological examination of the biopsy specimen showed marked sinusoidal dilation and focal sinusoidal occlusion with loose fibrous tissue (Fig. 3). Histologically, the disease process resembled focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) of the telangiectatic type. However, the lesion's diffuse infiltrative features on imaging made the diagnosis of FNH unlikely. There was no evidence of veno-occlusive disease or hepatocellular adenoma.

Microscopy findings of a biopsied liver specimen: (A) Severely dilated sinusoids (×40, HE), (B) Sinusoidal occlusion with loose fibrous tissue (×40, HE), and (C, D) Perisinusoidal fibrosis (blue, ×100, TRC).

The sum of clinical, imaging, and pathologic findings supported the diagnosis of peliosis hepatis. Possible etiologic factors included her history of ITP and corticosteroid use. Given that her platelet count remained stable around 30,000/µL, her steroid therapy was terminated. The patient recovered completely three months after steroid discontinuation, and remained stable without clinical symptoms or abnormal liver function tests over six months.

DISCUSSION

Peliosis involves parenchymatous organs and appears in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, lungs, parathyroid gland, kidneys, spleen, and liver.11 Peliosis hepatis is a rare vascular disorder in the liver that is associated with several drugs and chronic illnesses such as chronic wasting disease,1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,3 and bartonella infection.4 Drugs that have been associated with peliosis hepatis include oral contraceptives6 and anabolic steroids.5 It has been previously reported that untreated hematologic disorders including ITP can cause peliosis hepatis.12 However, the causes of peliosis hepatis are unknown in 20-50% of patients.13 Peliosis hepatis was first found by Wagner in 1861, and was later named by Schoenlank in 1916.1 Although the pathogenesis is unknown, several hypotheses have been studied. Some researchers reported that toxic or viral substances induce hepatocellular necrosis with a sinusoidal dilatation, while others proposed a congenital vascular malformation or an active vessel proliferation.11

Patients with peliosis hepatis can be either asymptomatic or present with various clinical features including hepatomegaly,7 portal hypertension,10 fatal intraperitoneal hemorrhage,8 or liver failure10 requiring liver transplantation.9 Although the incidence of peliosis hepatis is comparatively low, at 0.13%, it has high risks.14 The size of the peliotic cavity and the extent of liver involvement predict clinical features. Patients with small cavities and sinusoidal dilatations are usually asymptomatic, but patients with large cavities often have more prominent clinical manifestations.7

The diagnosis of peliosis hepatis is often missed or delayed because it is usually asymptomatic, and its radiologic appearance closely resembles a hepatic malignancy or multiple abscesses. In reality, the imaging findings of peliosis hepatis vary depending on the underlying disease and the various stages of the blood components.15 On contrast-enhanced CT, peliosis lesions typically show early globular enhancement and multiple small, central accumulations of contrast material during the arterial phase, with a centrifugal progression of enhancement during the portal venous phase.16 On MRI, the signal intensities of the lesions largely depend on the stage and the status of the blood components.16 On T1-weighted images, lesions are hypointense or heterogeneously hypointense if complicated by hemorrhage. On T2-weighted images, they are usually hyperintense compared to the liver parenchyma. Hemorrhagic parenchymal necrosis and thrombosed cavities manifest as non-enhancing areas. The differential diagnosis of peliosis hepatis may differ according to the actual imaging findings. On T2-weighted images, high signal together with early lesion enhancement can mimic HCC or hypervascular metastasis,17 while a bright T2-weighted signal and persistent delayed-phase CT or MRI may help distinguish peliosis hepatis.

Histology is used to further elucidate imaging findings and confirm the diagnosis. A percutaneous needle biopsy can be used to obtain a specimen. In this case, our patient's liver biopsy was characterized by several histologic findings, including massive dilation of the sinusoids, peliosis lesions, and sinusoidal occlusion by loose fibrosis. Few studies address histological changes in the liver of patients with ITP. In a 1988 study by M.E. Lafon, wedge liver biopsies were performed on 10 patients with ITP during splenectomy.1819 The study found histological evidence of sinusoidal fibrosis with accumulation of collagen types I, III, and IV, and laminin. They also found transformation of perisinusoidal cells to fibroblasts or myelofibroblasts. These changes are similar to those mentioned above as secondary changes in peliosis hepatis. In Lafon's study, he found no peliotic liver changes. The patients in his study had been treated with corticosteroids for over 3 months, so one cannot rule out steroid effects on the liver, although we could find no reports of steroid therapy causing liver fibrosis. We were also unable to find a case report with combined severe fibrosis and peliosis hepatis, which co-occurred in our own patient. We hypothesize that her peliosis hepatis first developed in association with corticosteroid therapy, leading to ECM accumulation secondary to the combined effect of ITP and perisinusoidal fibrosis.

On review of the literature, no authors reported an evidence-based treatment for peliosis hepatis, although several reported spontaneous resolution after treatment of associated conditions or withdrawal of the precipitating drug.20 One article described hepatic artery embolization and partial hepatectomy in a case of hepatic rupture or hemorrhage,3 stating that emergency liver transplantation is the ultimate treatment in cases of impending hepatic failure. Despite the lack of imaging follow-up in our patient, we consider her peliosis hepatis resolved, as she has remained stable without clinical symptoms or abnormal liver function tests over 6 months.

This case is an important contribution to the literature on peliosis hepatis, as it is a rare disease that is not often diagnosed in living patients.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

AFP

acid fast bacili

CT

computed tomography

FNH

focal nodular hyperplasia

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HIV

human immuodeficiency virus

ITP

idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging