Primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking acute hepatitis

Article information

INTRODUCTION

Primary hepatic lymphoma is a rare extranodal form of lymphoma. it may initially present as hepatic dysfunction resembling acute hepatitis, and clinical diagnosis of the disease could be delayed and complicated, occasionally progressing to fulminant hepatic failure. Here we report the featured radiologic findings of primary hepatic lymphoma on serial follow-up of ultrasonographic and computed tomography (CT) examinations.

CASE

Case 1

A 57-year-old woman visited the emergency department at our hospital with generalized edema which developed a month previously. Her clinical history did not include any specific disease, and her family history was unremarkable. On physical examination, there was no abnormal finding except splenomegaly. The initial results of laboratory investigations were as follows: serum total bilirubin level of 3.0 mg/dL (normal range: 0.2-1.2 mg/dL), direct bilirubin level of 1.5 mg/dL (normal range: 0-0.4 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 54 U/L (normal range: 0-37 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 10 U/L (normal range: 0-40 U/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γGT) of 177 U/L (normal range: 11-43 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 240 U/L (normal range: 42-98 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) by 842 U/L (normal range: 211-423 U/L). Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thrombin time (aPTT) were initially within normal range. On peripheral blood cell count, all of the blood cell counts declined: red blood cell count of 3.12×106/mL (normal range: 4.2-6.3×106/mL), white blood cell count of 1.5×103/mL (normal range: 4-10×103/mL), and platelet count of 80×103/mL (normal range: 130-400×103/mL). The test for peripheral blood cell morphology also showed normocytic, normochromic anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Serological tests for hepatitis A, B and C viruses, Ebstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus were all negative.

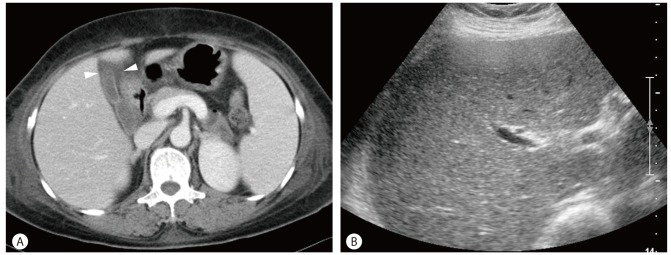

Initial abdominal CT demonstrated hepatosplenomegaly, edematous wall thickening of the gallbladder, and effusion in the pleural and pericardial spaces. The initial diagnosis was acute hepatopathy with unknown cause. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy in the abdomen (Fig. 1A). On the abdominal ultrasonography (US) performed 3 days after the CT study, the echogenicity of the liver parenchyma was mildly coarse, supporting the CT diagnosis of parenchymal disease (Fig. 1B).

A portal phase CT scan of a 57-year-old woman shows hepatosplenomegaly and diffusely edematous wall thickening of the gall bladder (arrowheads). (A) There is no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. (B) After 3 days, abdominal ultrasonogram shows mild coarseness of the hepatic parenchymal echogenecity.

On the 10th hospitalized day, the laboratory evaluation showed deteriorating hepatic function: the international normalized ratio (INR) of PT was elongated to 1.81. The levels of total and direct bilirubin were also elevated to 27 and 16 mg/dL, respectively. As the next step, US-guided liver biopsy was performed using an automatic biopsy gun (Tru-cut, TSK laboratory, Japan). Two pieces of specimen were obtained, and histopathology showed numerous lymphocytes infiltrating into the periportal space and hepatic sinusoid. On high-power field of microscopy, variably sized, hyperchromic nuclei with mitotic activity in the lymphocytes were seen. The results of immunochemical profiles of this specimen revealed B cell lineage. The final pathologic diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

The patient refused to receive any treatment for the lymphoma and expired 27 days after initially being hospitalized due to hepatic failure.

Case 2

A 59-year-old man visited the gastroenterology department at our hospital with abdominal bloating. His clinical history did not reveal any specific disease, and his family history was also unremarkable. On physical examination, no abnormality was found, and the results of laboratory investigations were also normal. Initial abdominal US demonstrated mild coarseness of the liver without any focal lesion (Fig. 2A).

Initial hepatic ultrasonography of a 59-year-old man shows normal parenchyma echogenicity of the liver (A). On the 9th day from the initial ultrasonography, decreased background echogenicity of the hepatic parenchyma with diffuse periportal tracking (arrow) are noted (B). On the 17th day, ascites is seen in the perihepatic space (arrow), and the parenchymal echogenicity is coarser than in the previous study (C). The thickened gall bladder is completely collapsed (D).

Five days after the initial abdominal US, he revisited the emergency department with newly developed symptoms including high fever over 39.5℃, general weakness, cough and sputum. On physical examination performed on his second visit, mild hepatomegaly and tenderness on the right upper quadrant were identified. There were no palpable lymph nodes. The laboratory evaluation showed deteriorated hepatic function: AST of 200 U/L, ALT of 20 U/L, γGT of 223 U/L, ALP of 477 U/L, LDH of 1,060 U/L. The levels of total and direct bilirubin were highly elevated to 27 and 16 mg/dL, respectively. On peripheral blood cell count, all of the blood cell counts declined: red blood cell count of 3.31×106/mL, white blood cell count of 5.5×103/mL, and platelet count of 110×103/mL. Serological tests for hepatitis A, B and C viruses, Ebstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus were all negative. Abdominopelvic CT scans taken at the emergency department showed hepatosplenomegaly with collapsed gallbladder, suggestive of acute hepatitis.

Follow-up abdominal US performed 9 days after the initial study revealed a further decrease in the background echogenicity of the hepatic parenchyma as well as hepatomegaly. The gallbladder was collapsed and accompanied by diffuse wall thickening (Fig. 2B). Eight days later, the hepatic echogenicity had become coarser and hepatosplenomegaly was markedly aggravated. Moreover, the gallbladder wall was more thickened and the amount of ascites was increased (Fig. 2C, Fig. 2D). The changes observed on serial US and CT imaging resembled those observed in progressively worsening acute hepatitis, leading to the diagnosis of idiopathic fulminant hepatopathy.

As the next step, US-guided liver biopsy was performed using an automatic biopsy gun. Two pieces of specimen were obtained, and the histopathology demonstated numerous lymphocytes mainly infiltrating into the periportal space. On the high-power filed of microscopy, lymphocytes with nuclei of variable size and mitotic activity were seen. The result of immunohistochemical profiles of this specimen revealed peripheral T-cell lymphoma. However, the special stain for γδ T-cell receptor was negative, and the final pathologic diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, was reached.

The disease was not responsive to chemotherapy using cyclophosphamide hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (CHOP), and rapidly progressed to multiple organ failure with severe sepsis and pancytopenia. The patient eventually expired three weeks after admission.

DISCUSSION

Hepatic involvement of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma can be divided into primary hepatic lymphoma, secondary involvement of systemic lymphoma, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Secondary involvement is the most common form of lymphoma in the liver, appearing in 16-40% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Primary hepatic lymphoma is defined as a lymphoma that is limited to the liver, without extrahepatic involvement.1 Most primary hepatic lymphoma originates from B cell lineage, with only few cases of T-cell lineage reported in the literature. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma is a very rare variant of mature T-cell lymphoma independently classified by the 2008 WHO classification.2 For the differential diagnosis, a liver biopsy should be performed along with immunohistochemistry studies.

Clinically, primary hepatic lymphoma is characterized by hepatosplenomegaly without lymphadenopathy. Systemic (B-type) symptoms are also common. The predominant laboratory findings are abnormal liver enzymes (elevation of AST, ALT, bilirubin, GGT, ALP, and LDH), especially, elevation of LDH and ALP and normal level of tumor markers such as alpha-feto protein (AFP) and carcinoembryogenic antigen (CEA). Diagnosis of the disease may be difficult at times due to the presence of misleading symptoms. There was a delay in the diagnosis in the cases reported herein because the clinical and laboratory features were similar to acute hepatitis.3-5 The presence of fever, hepatomegaly, elevated liver parameters and pancytopenia led to the false diagnosis of acute hepatitis or viral infection. Since the serologic tests were all negative, the possibility of viral infection could be excluded. The patients underwent radiologic evaluation to search for supportive evidence of acute hepatitis. Abdominal sonography and CT demonstrated features of hepatitis. Serial follow-up of US demonstrated a progressive course of the disease, which happens to be one of the characteristic findings of hepatic lymphoma. Finally, the liver biopsy was performed to evaluate unexplained downhill courses of the patients' status.

Although the major role of US in hepatitis is to exclude biliary obstruction as the cause of liver disease, the sonographic findings correlate fairly well with the clinical and histologic severity of disease in patients with hepatitis. In acute hepatitis, the liver and spleen are frequently enlarged. When parenchymal damage is severe, the parenchymal echogenicity is decreased and the portal venule walls are brighter than normal, making up a feature that has been named as the "starry night liver". However, these typical findings were relatively uncommon.6 Mural thickening of the gallbladder and hepatomegaly are other nonspecific findings in patients with hepatitis.7 In early hepatitis, the gallbladder is hypertonic, whereas in patients more than 9 days into the natural course of the disease, the gallbladder is hypokinetic with a large volume and diminished response to fatty meals. CT findings in hepatitis are usually nonspecific and the primary role of CT in patients with hepatitis is to exclude focal masses including hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatomegaly, thickening of the gallbladder wall and hepatic periportal lucency due to fluid and lymphedema surrounding the portal veins are the major CT findings in patients with acute hepatitis.

In conclusion, the characteristic radiologic findings of primary hepatic lymphoma may be similar to acute parenchymal liver disease, but demonstrate more aggressive features on serial follow-up imaging while they progress. Therefore, when the clinical and laboratory findings mimic those of hepatitis and the radiologic evaluation reveals acute liver parenchymal disease with an aggressive course, primary hepatic lymphoma should be included as differential diagnosis, and liver biopsy should be considered.

SUMMARY

Primary hepatic lymphoma is a rare manifestation of lymphoma. Clinical diagnosis of the disease could be delayed and complicated since it may mimic acute hepatitis. The radiologic findings of primary hepatic lymphoma may be similar to those of acute parenchymal liver disease although aggressive progression of the disease is usually observed on follow-up imaging. Therefore, primary hepatic lymphoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of acute hepatopathy that demonstrates a severe and aggressive course. Liver biopsy should be considered to confirm its diagnosis.

Notes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

AFP

alpha fetoprotein

ALP

alkaline phosphatase

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

aPTT

activated partial prothrombin time

AST

aspartate aminotransferase

CEA

carcinoembryogenic antigen

CT

computed tomography

INR

international normalized ratio

LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

PT

prothrombin time

US

ultrasonography

γGT

gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase